January 14, 2021

By Lea Nickless, Research Curator

It all began this past fall while in the midst of a routine task—I was researching biographical information on an artist active in the 1930s, Emigdio Reyes. A watercolor titled Mattecumbe, likely painted while Reyes was working on the Works Progress Administration (WPA) monument honoring the victims of the 1935 Labor Day hurricane in the Florida Keys, was to be included in The New Deal: Art Relief, now on view on the museum's first floor. Reyes' painting, his only piece in the Wolfsonian collection, depicts a worker in repose, juxtaposing the resting laborer with sub-tropical nature. As The Wolfsonian's research curator, I regularly track down information about works to be exhibited, alternating between sussing out the straightforward (identifying artists' birth and death dates) and investigating the arcane and intriguing. On a daily basis, I consult Google, scan genealogical search engines, and pore over online newspapers archives, sometimes making surprising connections.

The hair on my arms stood up when I clicked on a July 4, 1943 Miami News article related to Reyes and read its first sentence, "A one-man watercolor show will open at the Washington Art Studio, in the Washington Storage building." Deeper digging revealed that the show featured paintings of "scenes from Key West" and was so popular that its run was extended for ten days. How was it possible? Seventy-seven years ago, Emigdio Reyes had an exhibition featuring paintings from Key West in the very space in which we were installing Mattecumbe!

Now let's be clear. I've worked for Wolfsonian founder Micky Wolfson for a very long time. I remember our building when it was still the Washington Storage Company and not yet The Wolfsonian. I remember the large-framed, stoic, and slightly intimidating Mr. Mathews (Jim), son of E. Nash Mathews, one of two brothers who built Washington Storage in 1927. I remember Mr. Mathews selling Washington Storage to Micky in 1985. But I never knew about the Washington Art Studio, or Washington Art Galleries, as it was more commonly known—this precursor to the museum as we know it today was a revelation.

Energized by this discovery, I dove back into my research, eager to unearth other connections lost to time. Days went by, and all I wanted to do was hunt down artists, create timelines, and collect digital newspaper clippings—all to better understand and reveal a long-lost narrative. Fueling my drive was the certainty that I would find other hidden associations between The Wolfsonian and the Washington Art Galleries. I was right.

Painting, Harlem River, n.d. Ernest Lawson, artist. Image courtesy of Christie's.

This painting was on view at the Washington Art Galleries in 1942. It sold at Christie's in 1985 for $100,000.

One example, and one of the more sobering connections, was learning that in 1941 a painting by the late Ernest Lawson, Harlem River, was exhibited at the Washington Art Galleries. He was a big deal, a nationally renowned landscape painter who had moved to Coral Gables in the 1930s. In 1939, despairing over his failing health, Lawson took a bus to Miami Beach and walked into the ocean, his body later found floating off the beach at the foot of Lincoln Road. It was unnerving to realize that The Wolfsonian has in its collection Ernest Lawson's death mask, cast in plaster by Miami artist Gustav Bohland. How strange is that?

And that was just the beginning. As I continued to dig, it became increasingly clear that long before The Wolfsonian was a glimmer in Micky Wolfson's eye, artists he would later covet and collect exhibited in the very building he would eventually acquire. Further, the Washington Art Galleries collaborated in rich cultural programming firmly grounded in what decades later would become Micky's very particular bailiwick, including participation in the Exposition Internationale du Bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince in 1949, mirroring his deep fascination with world's fairs and expositions. Also, the Washington Art Galleries facilitated art classes for Second World War soldiers-in-training temporarily stationed in Miami Beach—this couldn't be more aligned with Micky's ethos, one that is based on promoting curiosity and exchange. It is as though everything has come full circle, and we didn't even know it.

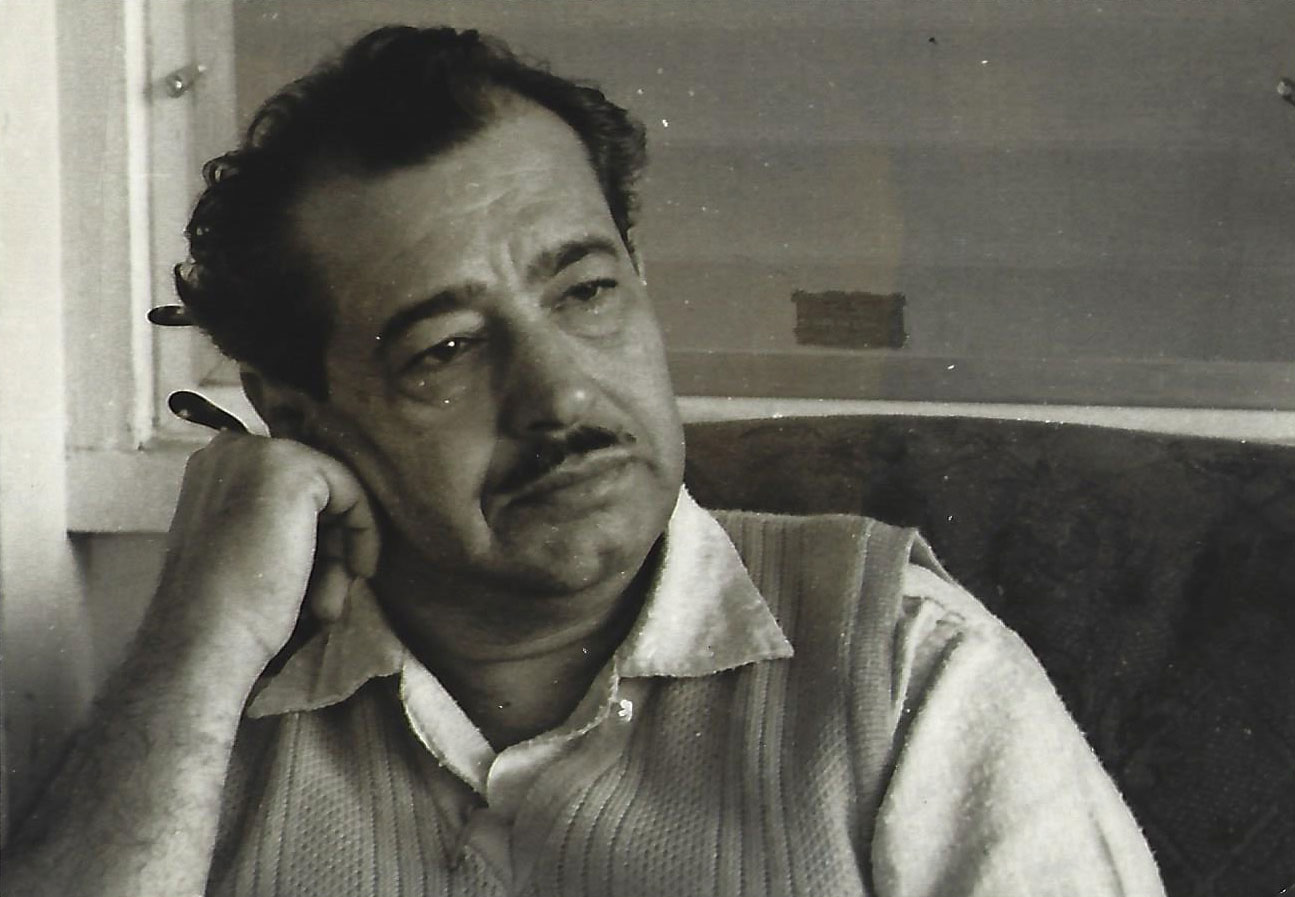

At the same time, I continued to research Emigdio Reyes. Born in Key West in 1897, his Cuban-born father was in the cigar-making business. In those days, Havana was essentially a suburb of Key West, more accessible than Miami, with people moving fluidly between the two locations. Reyes studied in Havana at the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts, then in New York at Grand Central Art School, and also with Ashcan School artist George Luks. He even assisted Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco with his massive mural installation The Epic of American Civilization at Dartmouth College, painted in the early 1930s. In addition to working on the Matecumbe Key hurricane memorial, he also taught art as part of the federal New Deal program and later at the University of Miami.

It wasn't easy tracking down Emigdio Reyes' descendants—I almost gave up. After scouring genealogical websites and finding a family tree that seemed to correspond, I sent the tree's administrator a message, and then a follow-up. Almost three months after my original inquiry, I received an email from Daniel M. Baeza, Emigdio's grandson! Elated, I called him immediately. Thankfully, Dan, a retired executive director at AT&T Labs, was happy to talk about his grandfather.

"He was a real character, a renaissance man," Dan told me. "He was able to do just about anything, always teaching himself new skills—he took apart family radios and television sets just so he could figure out how to put them back together." He also would sketch caricatures on any piece of cardboard or scrap of paper he could find. Dan also organized a conference call with his cousin, Emigdio's granddaughter, Diana Rassel. Together, they relayed a tale of an enigmatic creative, someone who marched to his own beat but was also like a sponge, eager to absorb new ideas and information. Emigdio was in the Merchant Marines during the Second World War and then, to satisfy his wanderlust, worked on cruise ships, starting on the SS Florida, which departed from Miami's Biscayne Bay to Havana and then later sailed out of New Orleans to South America and Portugal. He taught himself photography, voraciously documenting his travel experiences, bringing back film to develop in a makeshift darkroom. Diana said that Emigdio never lost his creative energy and curiosity for life and continued to paint and draw until the day he died at age eighty-eight. But, as far as I can tell, his only one-man exhibition was at the Washington Art Galleries.

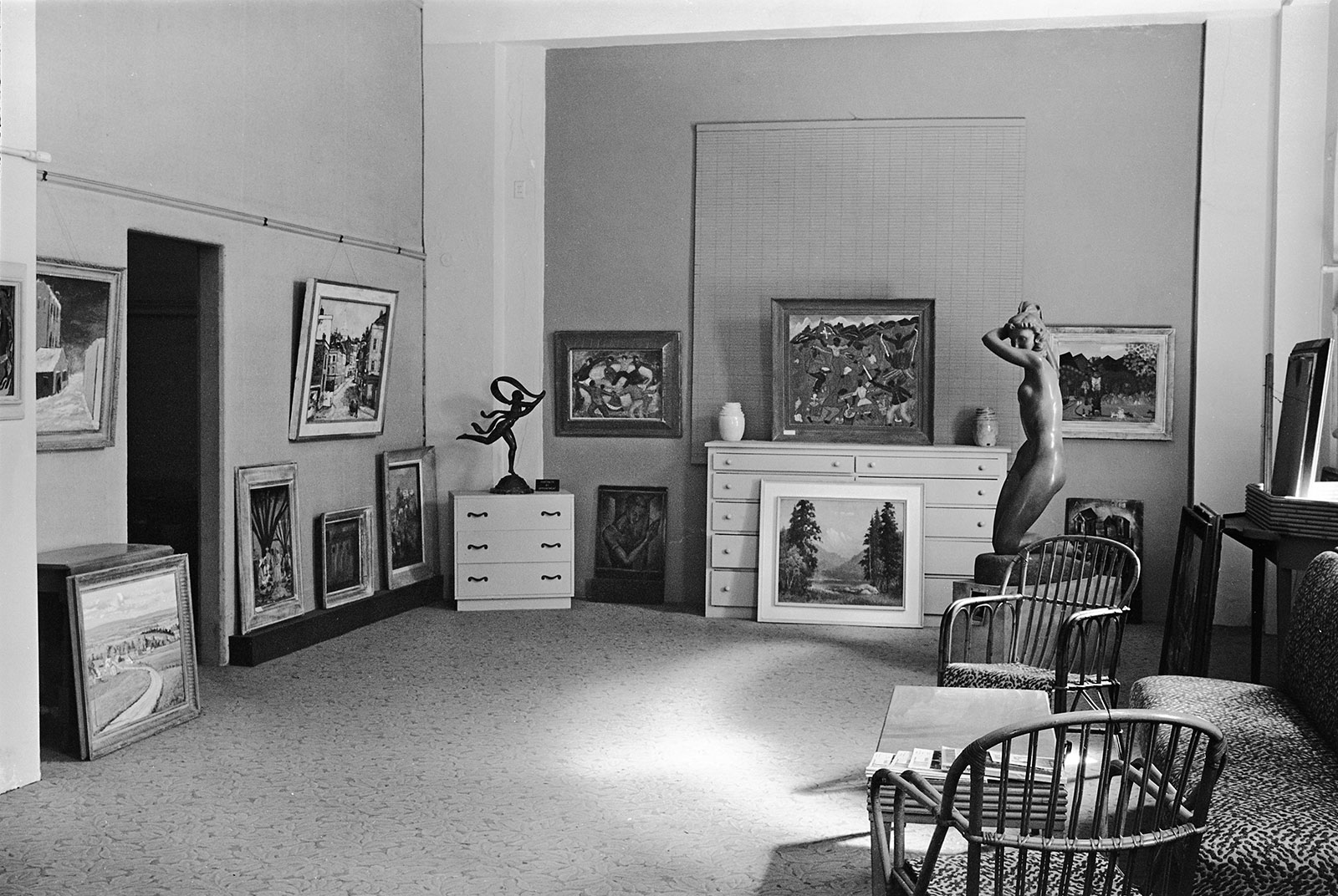

Photograph, Interior of Washington Art Galleries, c. 1942. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of J. F. Mathews, III, XB2020.11.1.1.

This early photograph of the interior of one of the galleries includes, at left, a 1921 bronze by Paul Manship, Atalanta (one sold at Sotheby's in 2015 for $250,000), and at right, Rainbow Fountain by Leno Lazzari (the Duke of Windsor commissioned a bronze casting that never materialized due to the war.)

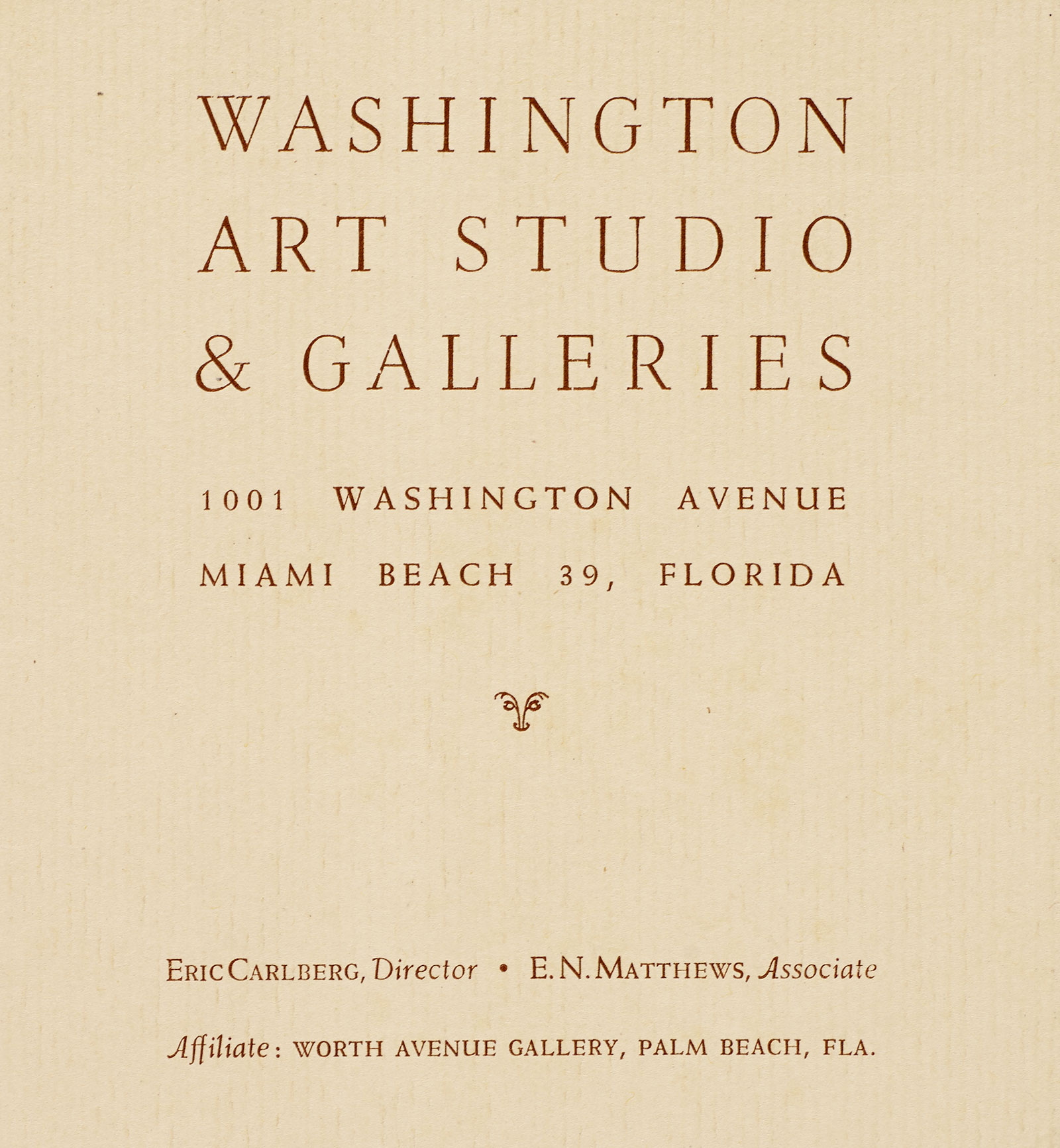

A little about the Galleries themselves, based on the evidence I've found so far: they were founded in 1940 by Nash Mathews, who had previously run an interior design business out of that space. Realizing that the war would bring a halt to new construction and the market for draperies, rugs, and furnishings, Nash shifted his focus to fine arts. He hired a knowledgeable and astute Swedish art historian, Dr. Eric Carlberg, who immediately established a robust exhibition schedule.

Brochure, Washington Art Studio & Galleries, c. 1941. Washington Storage, publisher. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, XB1993.6.

In addition to siting an affiliated Worth Avenue Gallery in Palm Beach, this brochure lists in its inventory modern paintings, watercolors, ceramics, sculptures, bas reliefs, and fountain figures. It also promotes services such as restoration and appraisals of old and modern paintings as well as objects d'art.

A fascinating mélange of artists presented their work at the Washington Art Galleries, including such luminaries as Paul and Margaret St. Gaudens (examples of Margaret's ceramics can be found in the Wolfsonian holdings, and Paul was the nephew of master sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, also in the collection), Marianna von Allesch (she studied with Bruno Paul in Berlin, immigrated to the United States, became an important designer in glass and ceramics, and later designed lamps for Morris Lapidus' Americana Hotel in Bal Harbor), Harold Liebmann (who supported his painting with stage performances of the "Cobra Dance" with his wife, Lola—they performed in nightclubs across the U.S. and South America), and Jack Hawkins (drawings from his 1942 portfolio "The Psychoses of War" were displayed in the galleries in yet another almost eerie foreshadowing of what the space would become so many decades later—you can't really get more "Wolfsonian" than a portfolio of surrealistic war-related drawings).

With each new connection, the significance of this research was validated—my time and efforts were not in vain. I loved the idea that long before the existence of The Wolfsonian, creative forces had been at work in the space we now inhabit. What I hadn't anticipated was the discovery of more directly personal associations, for Micky and for me.

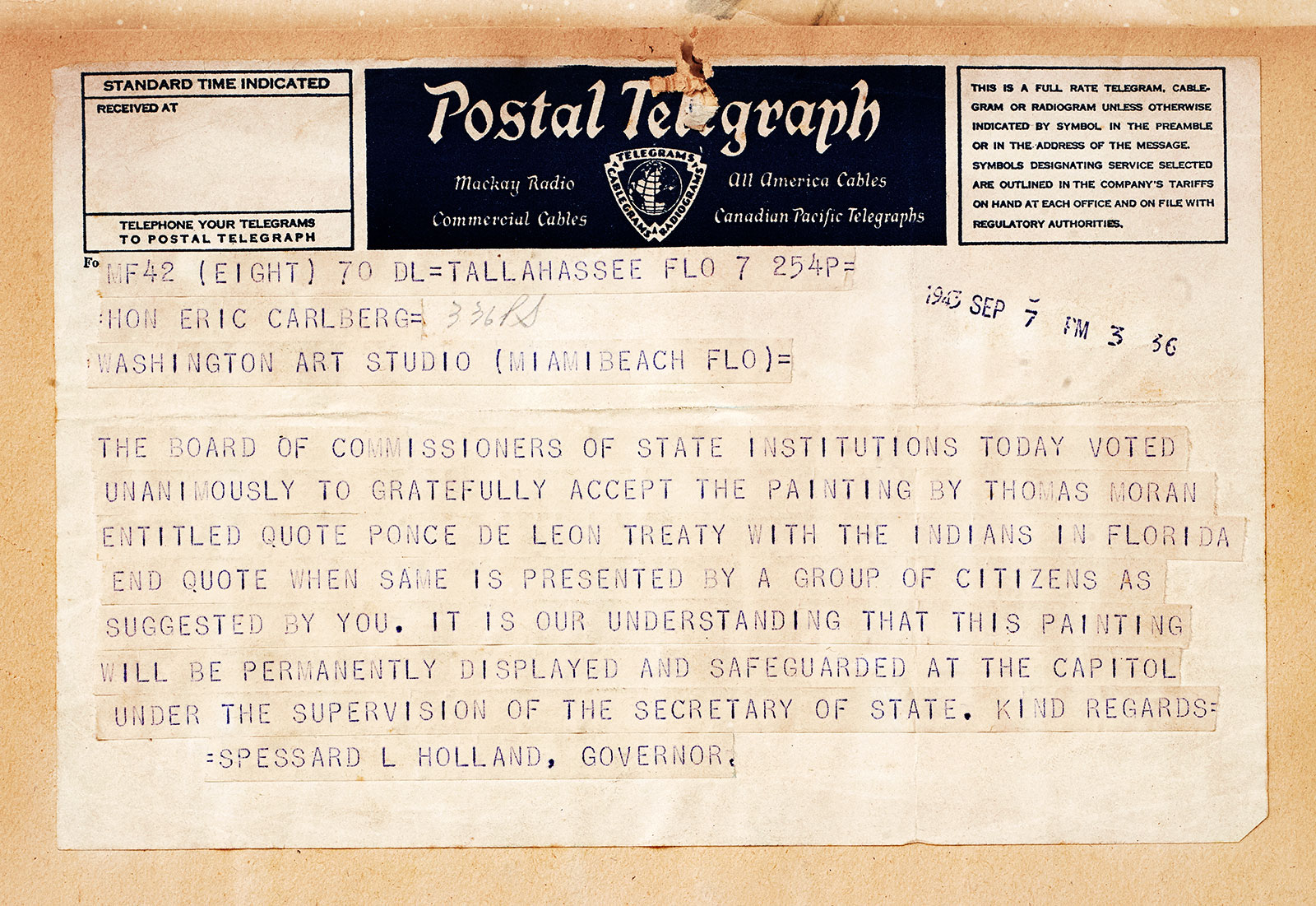

In 1943, an important large-scale painting by Thomas Moran, Ponce de León in Florida, was on view at Washington Art Galleries. One of the leading landscape painters of the time, Moran completed the Florida-themed work in 1878 with the expectation that Congress would purchase it for the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. This didn't happen, and the painting was acquired by Henry Flagler, then changing hands several more times before landing in Miami Beach. Wishing for the painting to remain in Florida, a plan was hatched to raise funds to place it on permanent display at the State Capitol in Tallahassee. Once again, an unexpected synchronicity—the sponsoring committee included Micky's father, Miami Beach Mayor Mitchell Wolfson! It is amazing to think that when Micky was just four years old, his father was working closely with Washington Art Galleries to broker this deal. Despite a telegram from Governor Spessard Holland acknowledging the painting's imminent arrival in Tallahassee, something went awry, the painting never made it to the Capitol, and it was sold to a furniture dealer and rancher in Oklahoma. Fortunately, the painting is now back in Florida in the collection of the Cummer Museum in Jacksonville.

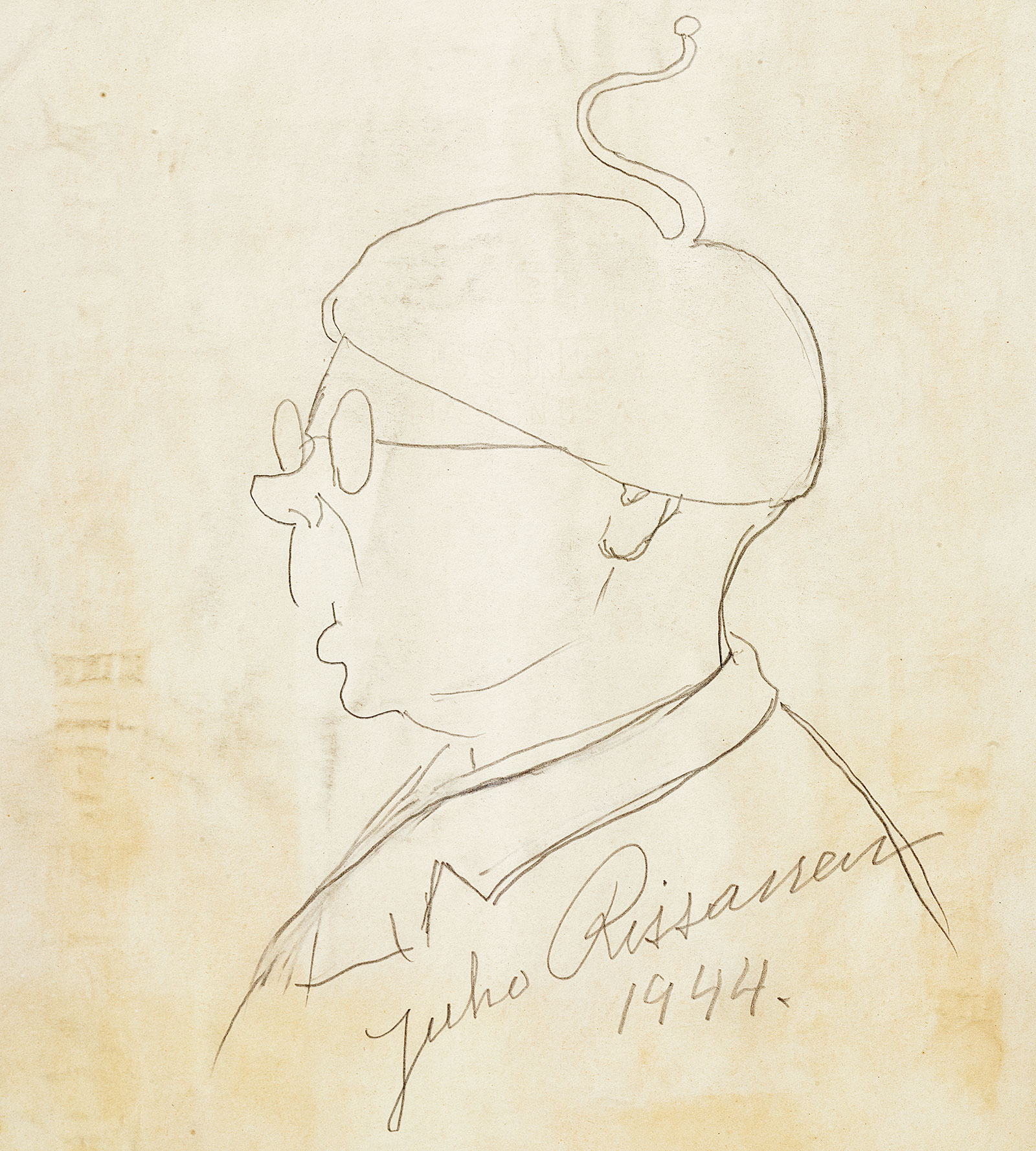

And then came my turn for a moment of truth. I came upon two scrapbooks filled with news clippings, photographs, and drawings related to the Washington Art Galleries in The Wolfsonian Library. Flipping through their pages, I found a business card and penciled self-portrait of Juho Rissanen, a prominent Finnish artist who had participated in the 1939 New York World's Fair. Stranded by the outbreak of the Second World War, he moved to Miami in 1940—living up until his death seventy years ago in the 1938 Coconut Grove home I bought with my husband in 2019. I immediately recognized Rissanen's name as one that had popped up when I researched the property!

It continues. I then learned that two works by Rissanen had been on view at the Washington Art Galleries according to a December 14, 1942, article in Miami News. And then another revelation, "when this art gallery opens its studio at 310-1/2 Worth Ave., Palm Beach…these paintings will be taken there." A double whammy. Two startling discoveries. Not only had Rissanen lived (and died) in my house AND exhibited paintings in the building where I have worked for many years, there was another gallery in Palm Beach associated with the Mathews brothers, one that the Wolfsonian team hadn't been aware of.

As I later learned, in 1942 Ned Mathews teamed up with his aunt Mary Benson to create a satellite gallery in Palm Beach, the Worth Avenue Gallery. It was the first major commercial gallery on Worth Avenue and under Mary Benson's direction achieved great success, eventually becoming an iconic fixture of the Palm Beach cultural scene.

The Washington Art Galleries and the Worth Avenue Gallery helped cultivate and sustain the careers of hundreds of artists over the years, even giving Emigdio Reyes his moment in the spotlight. The story of the relationship between the two galleries and the evolution of the Worth Avenue Gallery is fodder for another deep dive—one that we'll save for another time. In the meantime, as we search for new evidence, we can celebrate this newly remembered arts showcase legacy at 1001 Washington Avenue.