December 16, 2020

By Isabel Brador, digital assets + collection data manager, and Shoshana Resnikoff, curator

Museum professionals are the curious type. We want to know—about art, about objects, about history—and we place a high premium on expertise, a great quality but one that can sometimes lead to overconfidence. We become so sure in our own knowledge that we don't go back to the source and ask basic questions about our institution, our collection, and our visitors.

So how do we combat this kind of thinking? One answer lies in human-centered design (HCD), an approach to problem-solving and design that focuses on involving the human perspective in all steps of the experience-building process. In a previous blog post, our teammates Yucef Merhi and Jon Mogul ably explained the origins of our newest digital (and eventually in-person) interactive experience, Dial M for Micky. Generously funded by John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Dial M for Micky is the final product of The Wolfsonian's efforts as part of a cohort of museums around the country that were asked to challenge themselves to work in different ways, largely propelled by HCD principles.

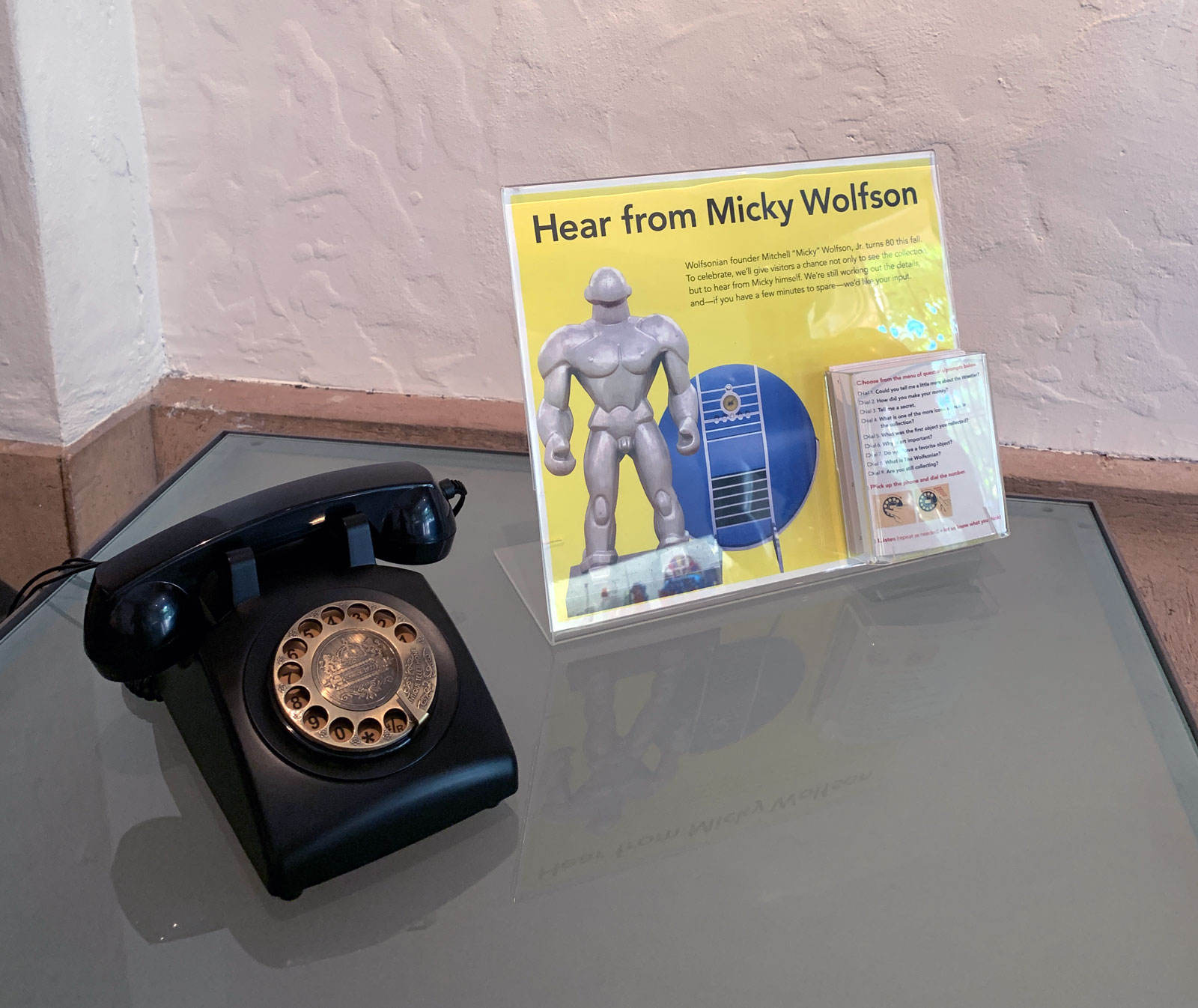

Core to HCD thinking are cycles of testing and reiteration. The original idea for Dial M for Micky was to create a physical space for visitors to hear from museum founder Mitchell "Micky" Wolfson, Jr. Wanting to connect to the museum's collection in some way, we saw that vintage telephones might be the ideal interface. In order to center the human perspective in our project, we needed to test two initial assumptions: 1) that visitors would indeed want to learn more about Micky, and 2) that they would enjoy using a rotary phone. This testing would require a bold move—to open up Dial M for Micky to outsiders' fresh eyes and ears, far before go-time.

Museum staff, constitutionally inclined to be perfectionists, rarely want to provide access to a project that is not yet complete or still evolving. To break this habit, Knight Foundation connected The Wolfsonian with the team at the design consulting firm and technology research lab BCG Maya, who helped us understand the importance of "working out loud," testing low-fidelity prototypes, and inviting our visitors to be our partners in development. By putting together a quick, low-cost version of the project that approximated the experience, we could test our theories and iterate new versions while preserving resources.

We began by surveying both members and visitors through emails and focus groups. By asking them about their previous knowledge of Micky and their level of interest in learning more about him, we determined that visitors—both regular and occasional—were indeed curious about the museum founder and his lifetime of collecting. Over the course of 4 weeks, we surveyed over 90 people.

From there, we tackled the prototype. The Wolfsonian purchased a reproduction rotary telephone (fun fact: the design is a knockoff of Henry Dreyfuss' 1937 Model 302 telephone designed for Bell Labs!) and hooked it up to a digital tablet loaded with audio clips of Micky taken from interviews over the past decade. Then we set up shop in the museum's lobby for dedicated shifts, two people manning the testing table at a time.

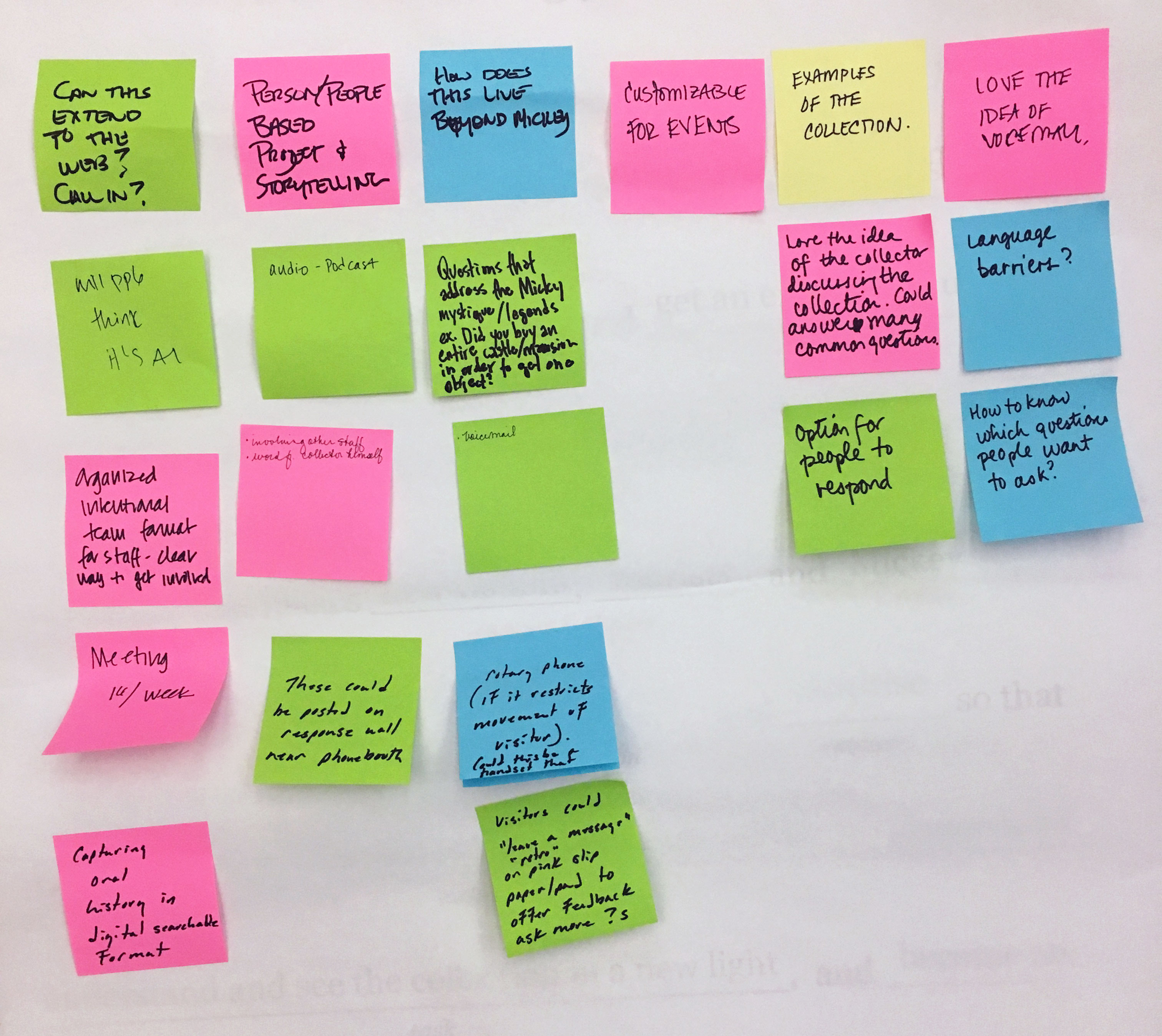

In 6 weeks, we tested 45 visitors and recorded their reactions and feedback. We discovered that once we explained the project, most folks were happy to help. The term "co-creation" gets tossed around in creative and design industries, but it's useful here as well—our guests understood that they could help shape the look and feel of a museum experience, and that made them invested.

Testing was simple: the user chose a prompt from a list of audio options, the "operator" queued up the clip on the attached tablet, and after using the rotary dial to "ring" the associated number, the operator pressed play and the audio came through the rotary handset, simulating the experience of operating an actual telephone. Extremely low-fi, it was a quick-and-dirty approximation of our ideal interactive.

We learned two very important things from our testing phase. First, we had correctly assumed users would appreciate using the phone, though their reasons were different from our expectations. Older visitors who had experience with rotary phones enjoyed interacting with the technology of their youth; we saw muscle memory kick in, such as when a user would cover the mouthpiece to speak with us, as if they were worried that "Micky" might overhear at the other end of the line. Younger visitors, meanwhile, were baffled by the rotary mechanism and delighted to learn how it worked. Even our colleagues learned something new by operating the test phone—one had what she described as an "embarrassing lightbulb moment" when she realized the origin of the word "dial" as a verb for calling.

We also learned what it was that visitors most wanted to hear from Micky. Being object-focused people (we work in a museum, after all), we had assumed that visitors would like to hear his view on the art held in the Wolfsonian collection. Instead, they were far more curious about the why and how behind it all, rather than details of an object. "Why collect?" "What was his first object?" "Does he have a favorite?" As visitors asked these questions again and again during our focus groups and surveys, we pivoted from an object-focused interactive and scheduled new interviews with Micky to ask him these bigger-picture, personal questions. True to HCD principles, visitors wound up having a direct impact on the project's final content.

Perhaps the most important thing about the testing phase of the Dial M project is how it has come to inform aspects of our work beyond the interactive itself. Not only have we learned more about our visitors, their knowledge of the museum, and their interest in the people and objects that make it, but we've also discovered the value of asking those questions in the first place. In the year since we began testing the Dial M for Micky prototype, we've completed surveying and testing for two more projects—Dial M's digital iteration, and an upcoming online interactive called The Timeliner. In both cases, testing revealed important information about user comfort levels, interests, and project direction.

We expect to prioritize user testing more and more as we develop exhibitions and programs and continue to ask our visitors and members to create experiences along with us. So, as we open our doors and welcome the public back into the galleries, don't be surprised to see two staff members at a table, clipboards or tablets in hand, asking you to help us answer some questions.

Read blog post 3 to continue the story of Dial M for Micky's production.