October 29, 2020

By Jon Mogul, Associate Director of Research, Education, and Grants + Yucef Merhi, Curator of Digital Collections

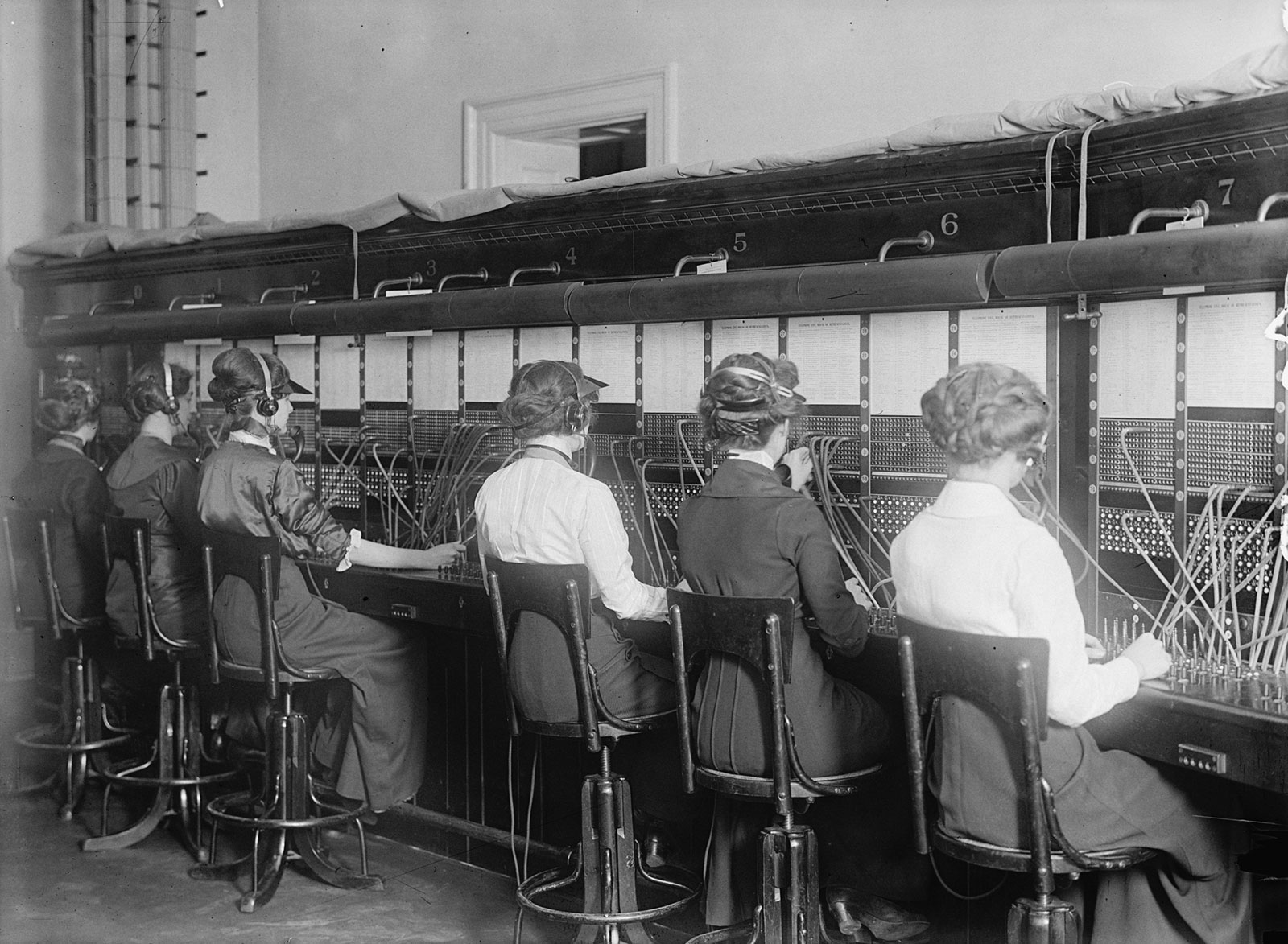

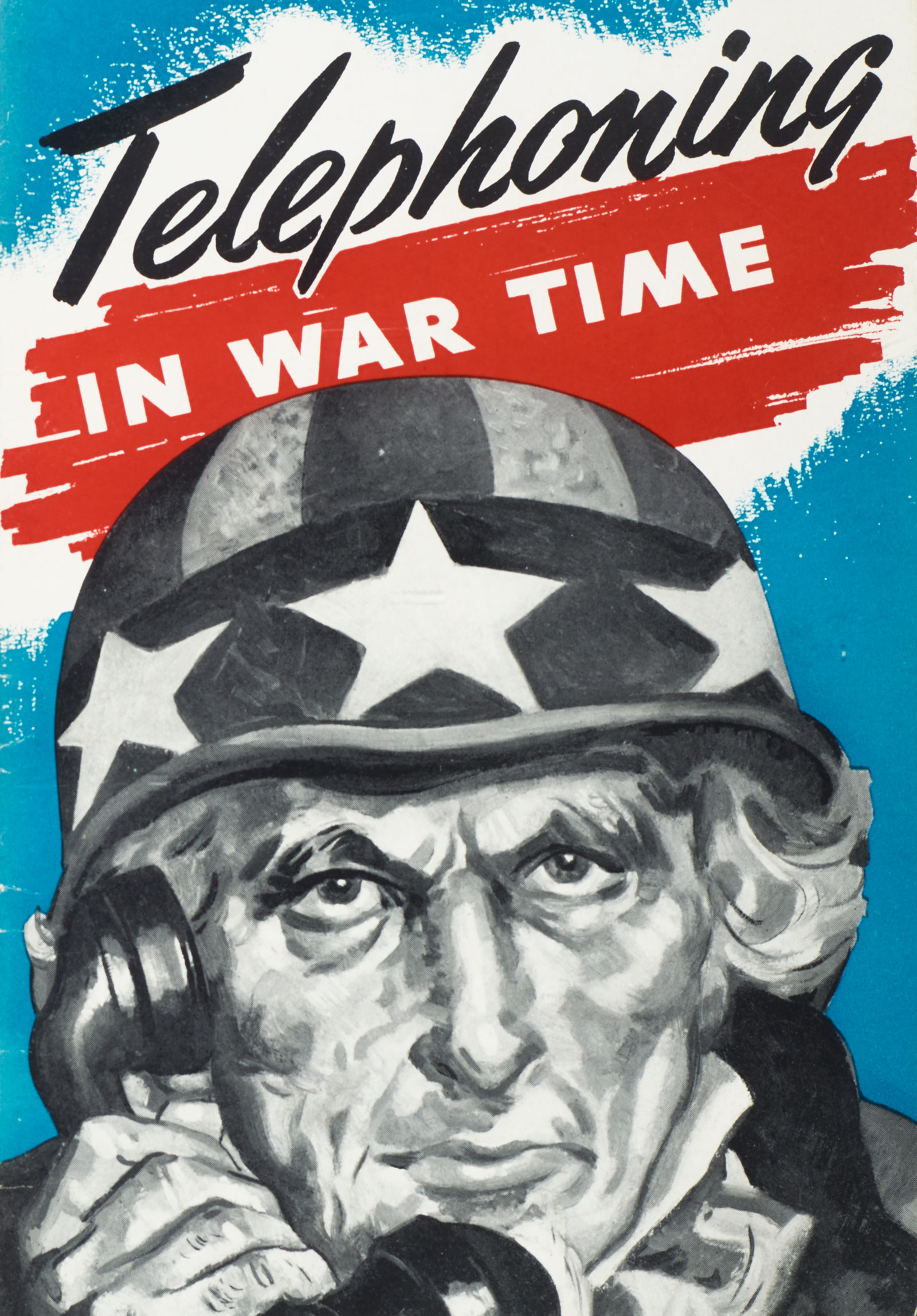

Almost exactly 100 years ago, thousands of telephone operators contracted the so-called Spanish flu, disrupting telephone service in New York City. The New York Times reported that the New York Telephone Company suspended service from half the city's public telephone booths, and asked customers to cut back on their phone use to make sure there would be capacity for handling essential calls. Telephone companies in Michigan, North Carolina, and other states made similar requests. The flu impacted telephone use in other ways, too: from Sydney to Kansas City, municipal authorities began a program of fumigating phone booths, and health experts urged users to keep their mouths as far as possible from the potentially germ-carrying receivers.

In the months since COVID-19 appeared on the scene, we heard echoes from these past events at The Wolfsonian. Across the world, COVID-19 has caused museums to consider how they will need to change once they welcome visitors back. One of the big questions relates to touchscreen interactives: will germ-conscious visitors want to use them, and is it responsible for museums to allow them to?

Even at a museum like The Wolfsonian, where we have employed touchscreens sparingly, we are facing similar questions and shifting our plans in response. That's where telephones come in.

Last year, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation invited The Wolfsonian to join a group of four museums, offering support for each to develop a technology-based feature. Knight made it clear that they cared not only about the end result, but also about how we got there. By the end of the exercise, the museums would learn new ways of working, based on the discipline of human-centered design, to integrate into future projects of all kinds. With that goal in mind, Knight provided not just funding but, at least as important, the opportunity to work with the Pittsburgh-based consultant group, MAYA Design (now a part of BCG Platinion), that specializes in HCD. A later blog post will discuss that process and what we learned from it—but this post is about the result.

The plan we hatched was to use technology to address a long-standing challenge: how to introduce visitors to our founder, Micky Wolfson. We knew from experience that most visitors have little idea who Micky is or why we are called The Wolfsonian. We believed that conveying more about Micky and capturing his intriguing, vivid personality in an entertaining, engaging way would help them understand the vision that animates The Wolfsonian and drives its collection. We had tossed around ideas such as a Micky Wolfson holograph, or an artificial intelligence Micky-bot, or a combination of both. But those ideas never got off the ground.

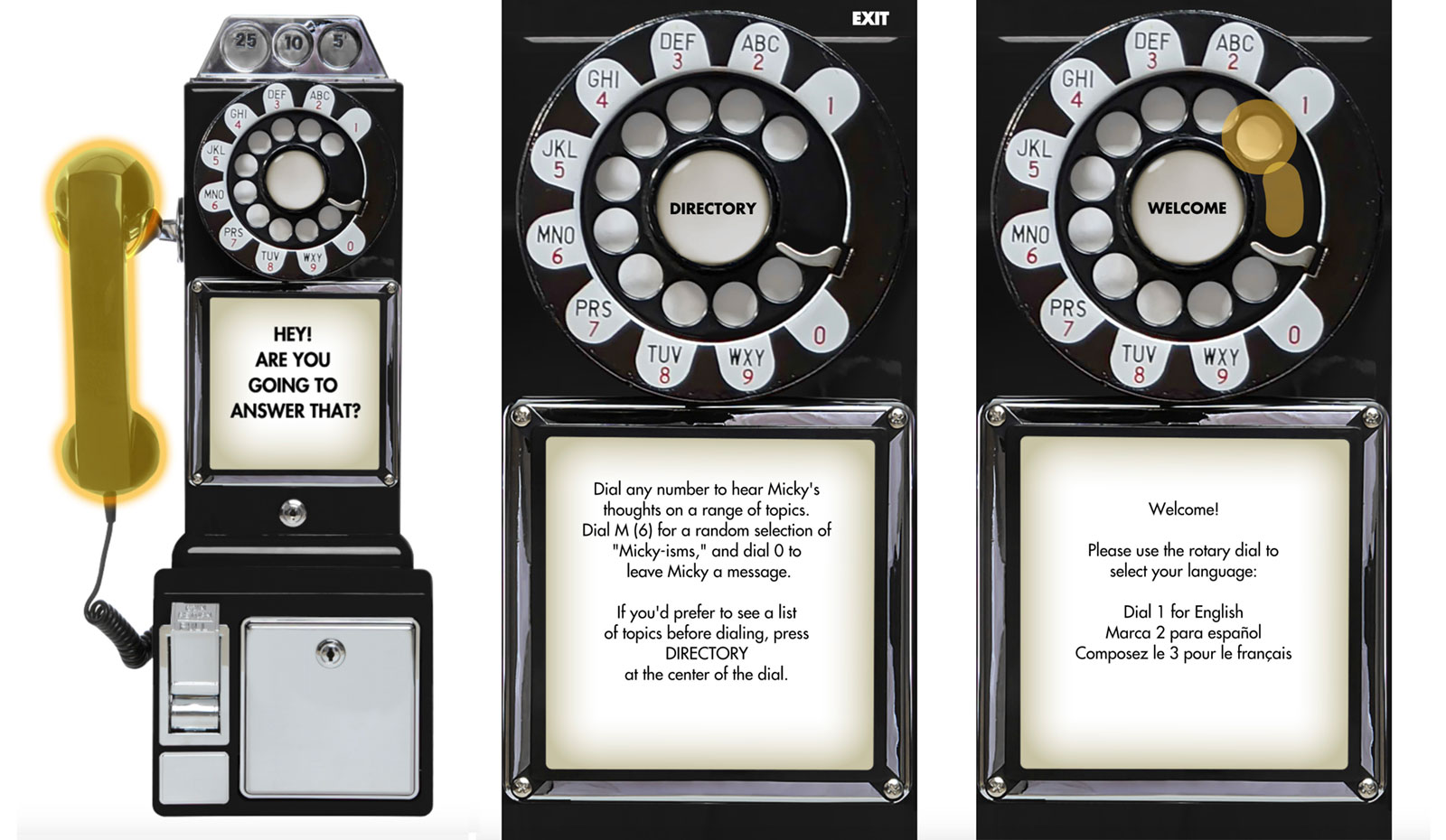

Our new idea seemed realizable, would give people an authentic experience with Micky, and might be fun as well. We already had recorded more than ten hours of audio and video interviews with Micky over the years, in which he talks about everything from his family, to his beginnings as a collector, to his ideas about art. What if we could invite visitors to "call" Micky and hear clips from those interviews? And what if, at the same time, we could give them a chance to do that with a vintage rotary telephone from the period that has always been the focus of Micky's collecting and The Wolfsonian's holdings?

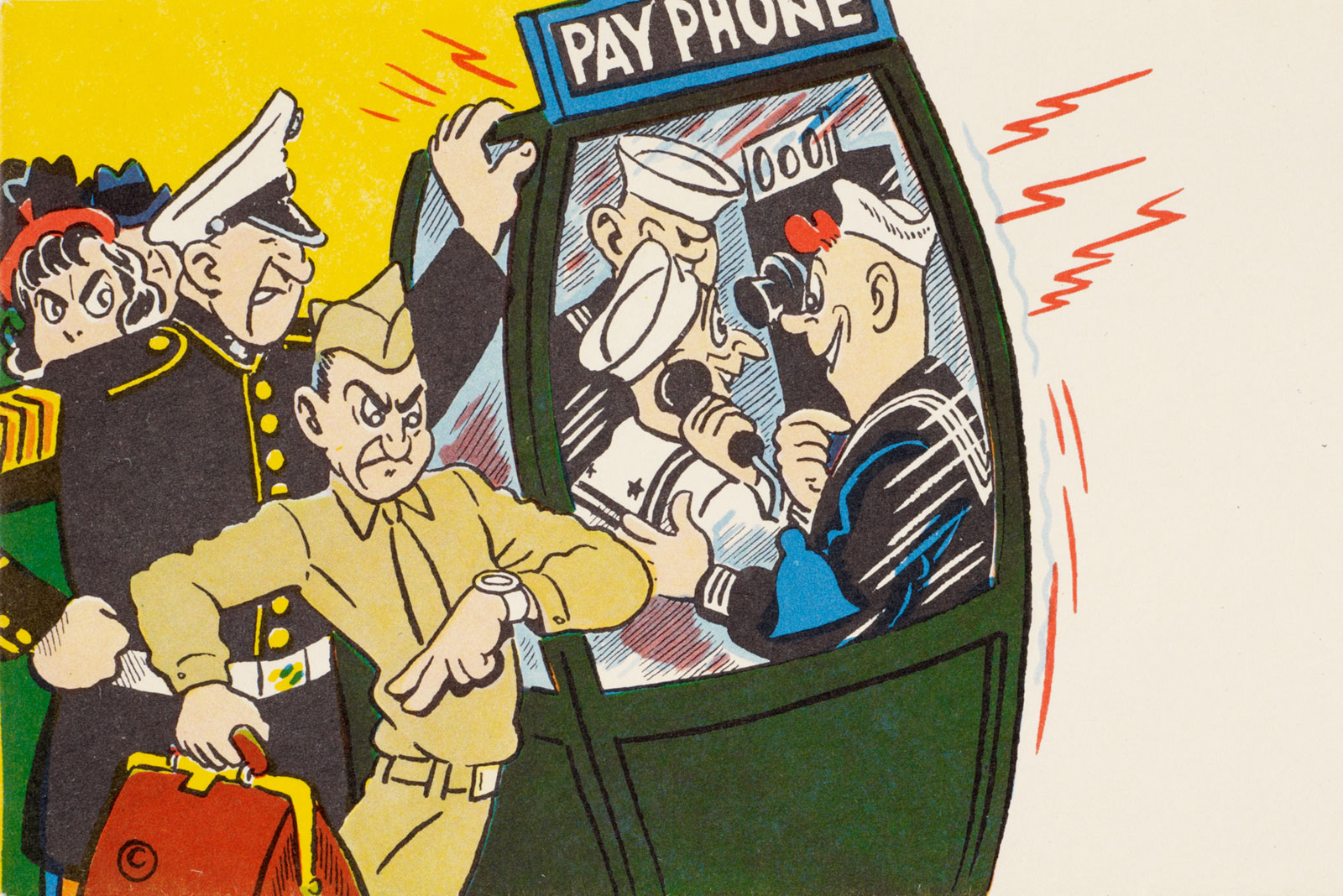

We formed a team and got to work, asking visitors what interested them about Micky, listening to old recordings of Micky, making some new ones, and selecting the best clips. At the same time, we investigated how to retrofit a rotary phone so that the dial could interface with a microcontroller that would, in turn, activate an audio clip corresponding to the number dialed. That turned out to be pretty complicated, but we eventually found a design studio called Iontank, also in Pittsburgh, that had done something similar for a PepsiCo promotion at SXSW and could get the job done for us. We bought three authentic 1950s payphones from a dealer in Wisconsin and had them shipped to Iontank. Then, we developed plans to install kiosks in our lobby, where visitors could use the phones. And we came up with a title, referencing a classic 1954 suspense film: Dial M for Micky.

Our goal was to have the phones installed and ready to pilot by the end of April. By late February, we were in great shape: Iontank had completed almost all their work and were getting ready to test and ship the phones to us. Then, at the beginning of March, a staff member suggested we should install a dispenser of antibacterial wipes near the phones. We have to admit that, until that moment, the part of our minds that was beginning to freak out about coronavirus had not connected with the part that was getting excited about Dial M. Within a couple of days, we'd decided not to roll out the phones as planned at the end of April. A few days later, it was clear that it would be a long time before anyone would want to handle our phones. And then, in mid-March, we temporarily closed the museum to the public.

Even though we hadn't seen them in person, we'd gotten pretty attached to our payphones. But it didn't take long to recognize that large parts of life were migrating to the web, and that Dial M should probably join that migration. With lots of input from our Wolfsonian colleagues, Knight, the consultants in Pittsburgh, and Iontank, we worked out a way to simulate the rotary phone experience using a web-based interface. The tactility of using a phone can't be replicated virtually, yet moving the project to the web offers a chance to reach a much larger audience beyond those who can visit the museum in person, and to incorporate some fun, interactive, and unexpected features that can't be accomplished in the analog world.

But what to do with our physical, retrofitted rotary phones, which are now safely stored in the museum? During the development process, we discovered through testing that people really enjoy using old phones. For baby boomers, it's a nostalgia trip; for younger people, it's a chance to use a vintage device that their parents and grandparents might have used, but has since practically disappeared from the world.

At this point, it's a waiting game until Wolfsonian visitors can use the rotary payphones as we originally intended. Hopefully, it won't be too long until a vaccine is developed and COVID-19 becomes an ugly memory, rather than our daily reality. When that happens, we will install our phones and let visitors start dialing. In the meantime, try Dial M and hear from Micky Wolfson through the world wide web—we hope you enjoy it!

Read follow-up blog posts 2 and 3 to continue the story of Dial M for Micky's production.