During the First World War (1914–18), U.S. investors scouted Cuba’s potential as a vacation destination for the wealthy. American travelers began to arrive in the 1920s, drawn to the island by modest postwar steamship fares, beaches untouched by winter frosts, and upscale amenities such as Oriental Park, a thoroughbred horse racetrack, and yacht, golf, and tennis clubs. After Prohibition took effect in the United States in 1920, Americans were attracted to Havana as a city that billed itself as an exotic, hassle‐free place to drink and gamble. Although tourism dropped off significantly during the Great Depression and Second World War, Cuban posters and travel brochures and Hollywood movies continued to portray the island as a dreamy tropical playground. These marketing efforts bore fruit after the Second World War, when middleclass visitors flocked to Havana to see its glamorous nightlife for themselves.

Touring Cuba by Sea, Air, and Automobile

Travel between the United States and Cuba was easy and inexpensive between 1919 and 1959. Steamship companies offered cheap fares to the island, and ferry service even allowed travelers to bring their cars. In the late 1920s, Pan American Airways took advantage of U.S. government subsidies and incentives to pioneer new routes to Latin America, including from Key West and Miami to Havana. The development of larger, long‐distance planes during the Second World War allowed for direct travel to Havana from New York and other American cities. After the war, middle‐class tourists, who could now afford quick trips that in the 1920s and 1930s had been available only to the wealthy, began to travel to the island. Cuba and the Caribbean became ideal destinations for vacationers–close to home, yet exotic.

High Society in Havana

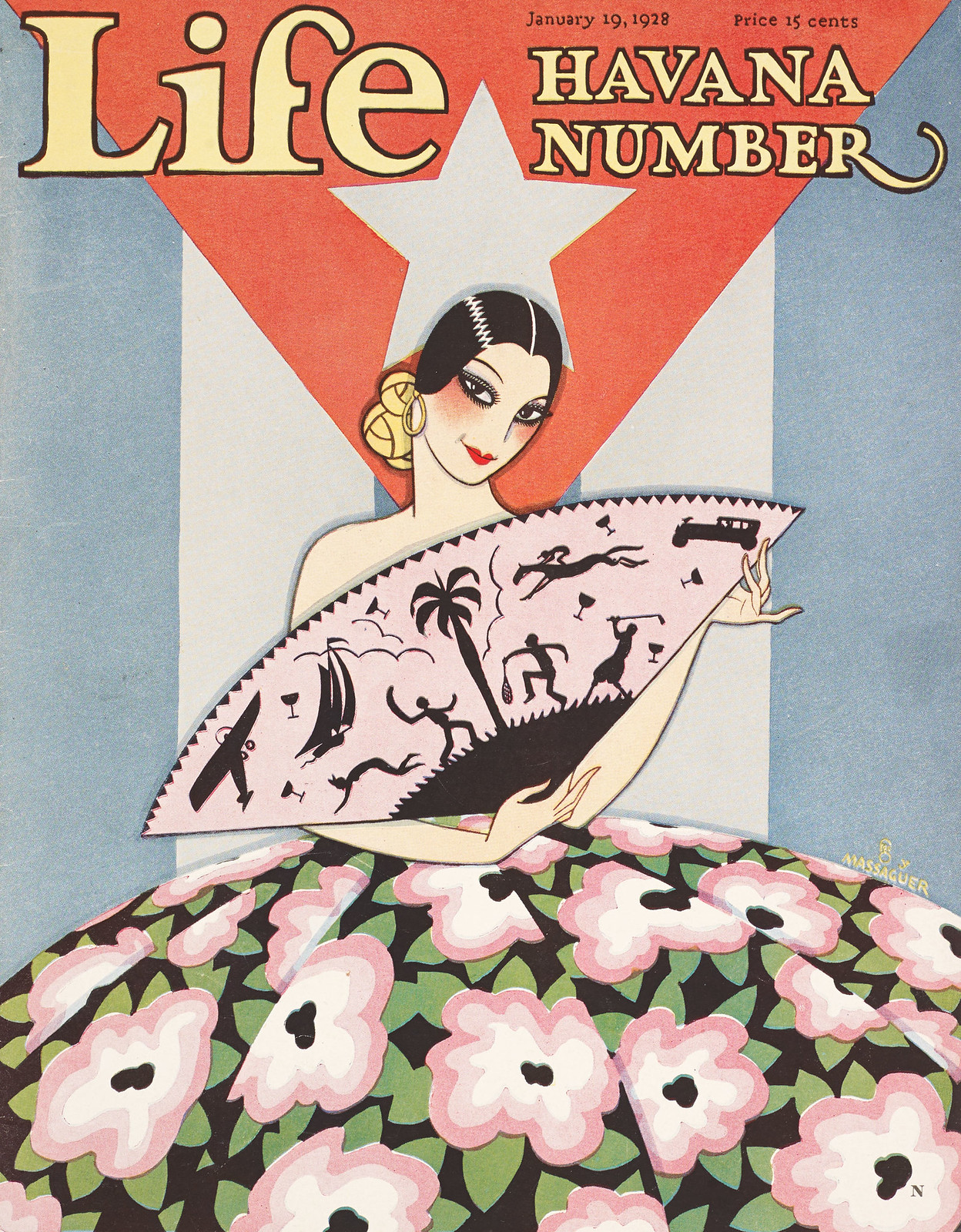

Between 1924 and 1931, Cuba experienced a surge in tourism, with tens of thousands of Americans arriving each winter. These mostly affluent, luxury‐loving visitors enjoyed golf and tennis, betting on roulette and horseracing, lounging at the stylish La Playa beach resort, dancing and sipping daiquiris at the rooftop garden of the Sevilla‐Biltmore Hotel, or simply taking a romantic stroll along the Malecón. By the decade’s end, Habaneros began encountering more budget‐conscious travelers among the six hundred thousand Americans who came between 1928 and 1932—that is, until the Great Depression and growing social strife on the island reversed the trend. When socialites from the United States began to arrive like migratory “ducks” in the winter, illustrators and satirists such as Conrado Massaguer and Andrés García Benítez created witty depictions of the visitors’ real or imagined encounters with Habaneros. Illustrations sponsored by the Cuban Tourist Commission or American advertisers invariably portrayed vacationers as graceful and debonair, but the covers of popular Spanish‐language magazines offered a more comical and critical view of tourists and their interactions with Afro‐Cubans.

Prohibition and Tourism

In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution went into effect, prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” Because Americans could no longer legally drink at home, “thirsty” tourists began flocking to the island of rum, rumba, and roulette. New bars and drinking establishments popped up all over Havana, and notable American saloon owners, such as Ed Donovan and Pat Cody, relocated there—competing with corner bodegas, which sold groceries and tobacco while serving food and drink. In the late 1920s, there were more than seven thousand bars in the city. Tourism advertisements, photographs, and even the cover art and lyrics of sheet music left no doubt that Havana was the place where serious drinkers should go. Prohibition was repealed in 1933, but by then Havana’s reputation as a world‐class vacation destination for lovers of spirits and gambling was firmly established.

Sloppy Joe's Bar and El Floridita

A native of Spain, the well‐traveled barman José García settled in Havana in 1919, soon after the passage of Prohibition in the United States. García opened a bodega on the corner of Zulueta and Animas Streets. The establishment’s carefree atmosphere earned it the nickname Sloppy Joe’s, and it became popular with Ernest Hemingway, and other American celebrities and tourists. El Floridita, a high‐end restaurant and cocktail bar famous for its seafood and frozen daiquiris, was another favorite haunt of Hemingway and vacationers.

A Party with Bacardi

During the era of Prohibition (1919–1933), the only cocktails available in the United States were in illegal speakeasies—where no amount of honey or fruit juice could mask the bitter flavor of cheap spirits. In Cuba, on the other hand, good rum was easy to come by. Originally consumed by plantation slaves, sailors, and pirates in the seventeenth‐century Caribbean, rum was rebranded as a gentleman’s drink after the enterprising Bacardí family worked to filter, distill, and age it in oak barrels. The cuba libre (rum and Coke), created after the Spanish–American War of 1898, remained popular in the twentieth century, but it was the daiquiri (named for the town in eastern Cuba where it originated) that won tourists’ hearts in the 1920s and after. Facundo Bacardí’s recipe entailed squeezing half a lime onto a teaspoon of sugar, adding a shot of Bacardí rum, and mixing the ingredients in an ice‐filled cocktail shaker until the outside was frosted. The drink was then served in a tall, chilled wine glass or flute filled with shaved ice.

Gambling on the Gamblers

In 1915, Harry (“Curly”) Brown invested in Cuba’s potential to become a winter retreat for horseracing enthusiasts by opening Oriental Park in the Marianao suburb of Havana. After the First World War, other American investors and wellconnected Cuban politicians followed suit, and the national legislature passed a 1919 tourism promotion bill that authorized several gambling ventures. Thus were born the Gran Casino Nacional de Marianao and Havana’s fame as the “Monte Carlo of the Western Hemisphere.” In the 1950s, a scandal broke after influential tourists complained about being cheated in “razzle‐dazzle” scams. President Fulgencio Batista invited his friend Meyer Lansky, a mobster and gambling impresario, to come in and clean house. Lansky and his associates, recognizing that a perception of honesty was essential to the popularity of games in which the house always won anyway, imported American croupiers, trained locals, and enforced fair gaming practices.

Building Booms

American investors and politically connected Cubans often worked together to build the highways and hotels needed to accommodate the increasing number of visitors, especially in the 1920s and 1950s. Fulgencio Batista, who took the presidency by military coup in 1952, established the Bank for Economic and Social Development, which provided approximately half the capital expended in new hotel construction over the rest of the decade. Batista also encouraged foreign investment in new hotels and renovations by offering casino concessions to those committing one million dollars or more—an offer his U.S. mob associates eagerly accepted. As a result, hotel room capacity doubled between 1955 and 1958, with the Cuban hospitality industry union financing a joint venture with Hilton Hotels International and Meyer Lansky clandestinely funding the building of the chic Havana Riviera.

Shopper's Paradise

Shopping went hand‐in‐hand with travel, which resulted in a thriving industry in Cuban‐themed souvenirs, including ashtrays, scarves, castanets, maracas, and handbags made of alligator skin and palm straw. Beyond the trade in tourist trinkets, Havana had high‐end shops and department stores, such as El Encanto, that catered to Cubans and foreigners alike. Wealthy and middle‐class Cubans also frequently traveled to the United States on special shopping junkets, such as the ones advertised in The Seahorse, a shoppers’ guide to Miami published by the P&O Steamship Line.