January 20, 2026

By Katarzyna Balug, Assistant Professor of Architecture, College of Communication, Architecture, and the Arts at FIU

All works from The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, unless otherwise noted.

One hundred years ago this month, four Spanish aviators set off on the first transatlantic flight between Spain and Argentina in a flying boat, designed by a Franco-German airplane designer and manufactured in Italy. It took them 19 days and 7 stops, with the longest nonstop passage stretching 2,305 kilometers (1,432 miles). The next year, Charles Lindbergh flew nonstop in a one-person plane between New York and Paris, an eye-watering 33-hour journey.

Following both flights, their pilots became instant celebrities at home and abroad, while their feats fueled public enthusiasm for global adventures on long-range flights. Together, they reinforced the necessity of stopovers: places where planes could land, refuel, and undergo maintenance while providing respite to the wealthy passengers along the long, arduous journey. Economically, stopovers could facilitate commercial flights in larger, heavier passenger planes unable to fly such long distances directly. Stopovers on existing islands were subject to political and financial negotiations; a manmade stop would alleviate such troubles.

Imagining a Floating Stopover

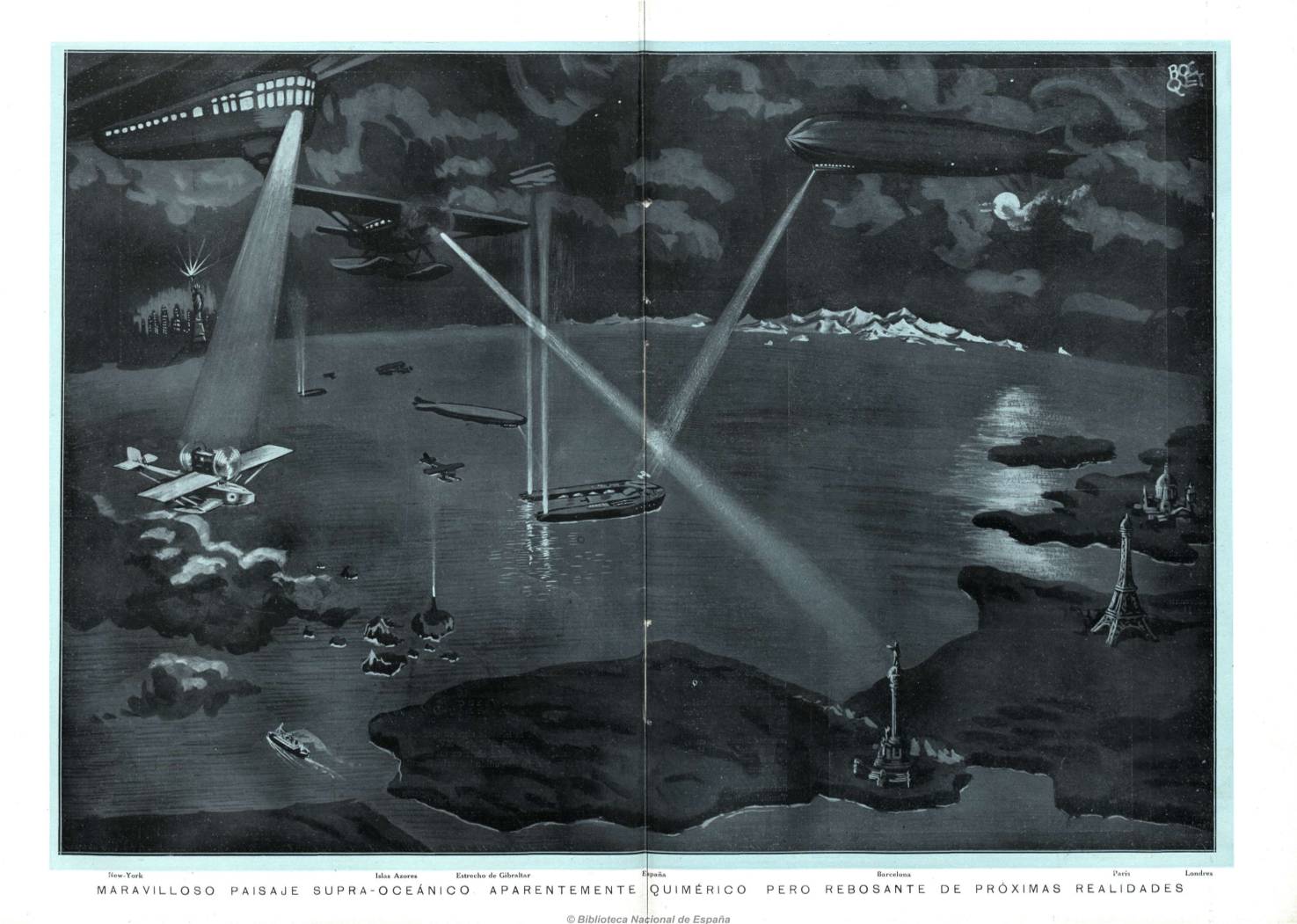

By the late 1920s, the race to develop a system of islands prompted designs across Europe and North America. In the 1930 issue of Ilustracion Ibero-Americana, writer Icaro Ibero urged Spain to beat North America and the rest of Europe in pioneering a floating stopover island in the middle of the Atlantic. He made the case a matter of nationalism and future prosperity, a means to connect Spain with her former colonies and allies in the New World.

The model on which he constructed his proposal was the design for "A Floating Island" by a young Parisian architect, Henri Defrasse, exhibited in the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. While this expo is remembered primarily for Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's seminal Barcelona Pavilion, Defrasse's little-known island designs offer their own insight into the 1920s evolution of modern architecture.

A Floating Island

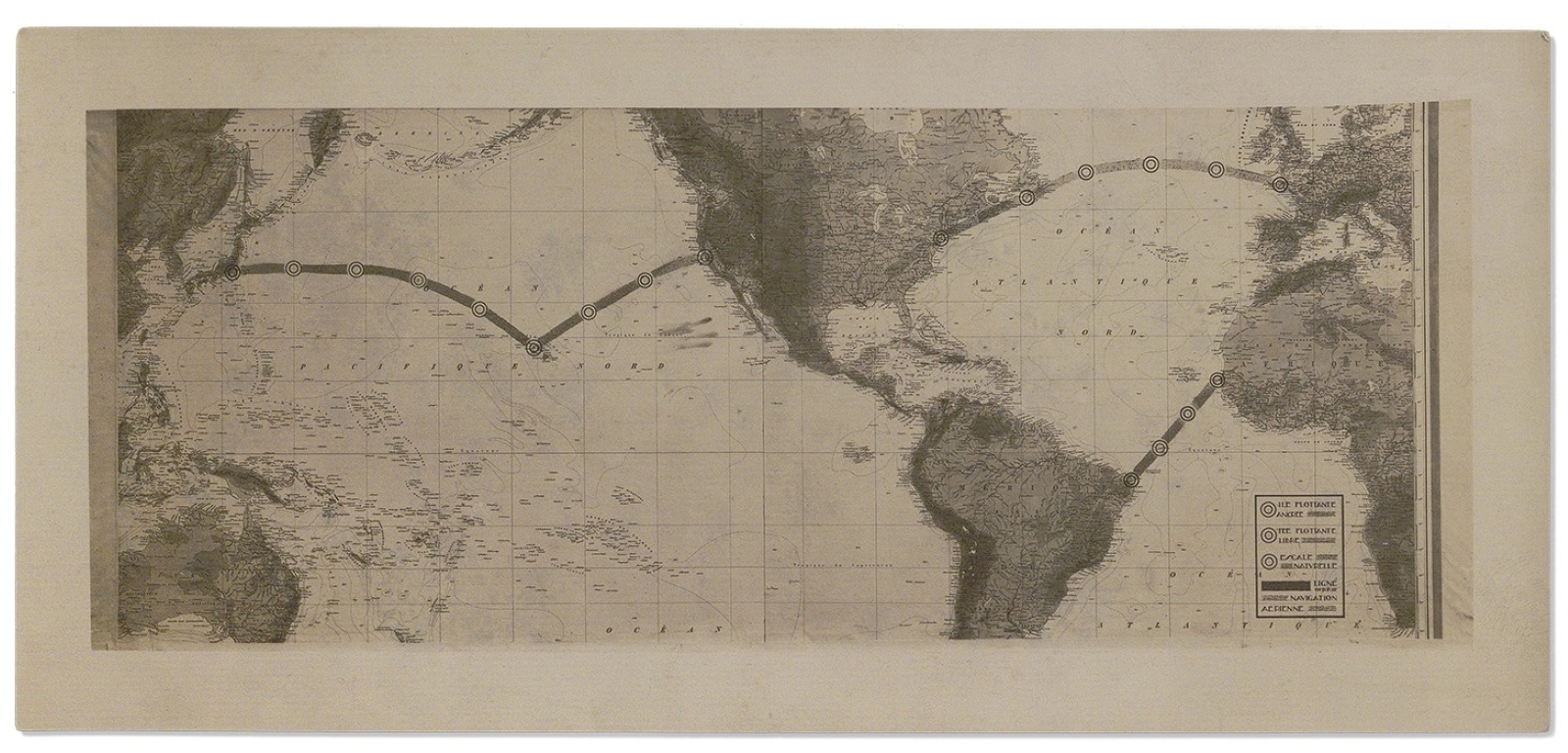

Defrasse first developed the idea around 1924 as a student at the École des Beaux-Arts in the atelier of his father, Alphonse Alexandre Defrasse, and Louis Madeline. Conceived several years before transatlantic flights, he proposed to connect Brest, on France’s northwestern coast, with New York via a network of floating islands. The island was to be a horseshoe shape of reinforced concrete modeled on a hull, with a bay of calm water isolated from the surrounding ocean and large enough for landing seaplanes, then considered a more viable method of consumer flight. In 1924, he received the École's Chenavard Prize for the project, along with considerable press.

Around the bay were mechanic shops and hangars for servicing the vessels and a modern 165-room hotel with dining and entertainment facilities. Defrasse's vision aligns with the sort of luxury then customary on transatlantic ships, while foreseeing that air travel would soon become equally popular.1

Revising the Design

In response to growing enthusiasm for passenger flight, Defrasse reworked the project for the French National Prize competition in May 1928. While the general form remained the same, Defrasse revised some of the technical aspects of takeoff and buoyancy to accommodate the growing sizes of available aircraft. He also transformed the island's aesthetics, and it is here that the project holds greatest interest.

The extensive drawings of both versions, available in the Wolfsonian archive, uniquely capture architecture's engagement with the paradigm shift occurring in the sociotechnical imaginary of 1920s France.

The First World War and the rapid proliferation of new technologies—airplanes, radio communications, the appearance of cars in the urban environment, and visions of the first glass skyscrapers—upended the norms of Western modern life, including its sense of speed, space, and form. Le Corbusier, whose notoriety was rapidly growing in Paris, documented these changes beginning in 1921 in a series of essays published in his journal L'Esprit Nouveau, and in book form in 1923 as Toward a New Architecture. These texts, along with The Decorative Art of Today published in 1925, completed the dismantling of ornament, considered superfluous and outdated, and criticized the aesthetics of the decorative arts. Instead, through anticipatory projects like the 1921 Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper (by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) and the 1925 Plan Voisin (by Le Corbusier), modernist architects elaborated a functional, "sober" aesthetic meant to call forth a citizenry for the industrial era by structuring their needs and desires through new forms.2

In the text accompanying his competition entry in May 1928, and later reprinted in the inaugural issue of the Spanish journal Illustración Ibero-Americana, Defrasse echoes Le Corbusier in summarizing his changes to the island's design: "The general principles that guided me are the same as those I followed in my earlier studies, but I have made a point of re-examining certain specific questions, such as takeoff, which is particularly delicate for heavily loaded aircraft. I have worked to ensure ever better nautical qualities and to simplify the forms through a logic of sobriety." The word "sobriety" references the search for "new sobriety," or "new objectivity" (Neue Sachlichkeit) through 1920s Modernism primarily in Germany and France.

From Monument to Machine

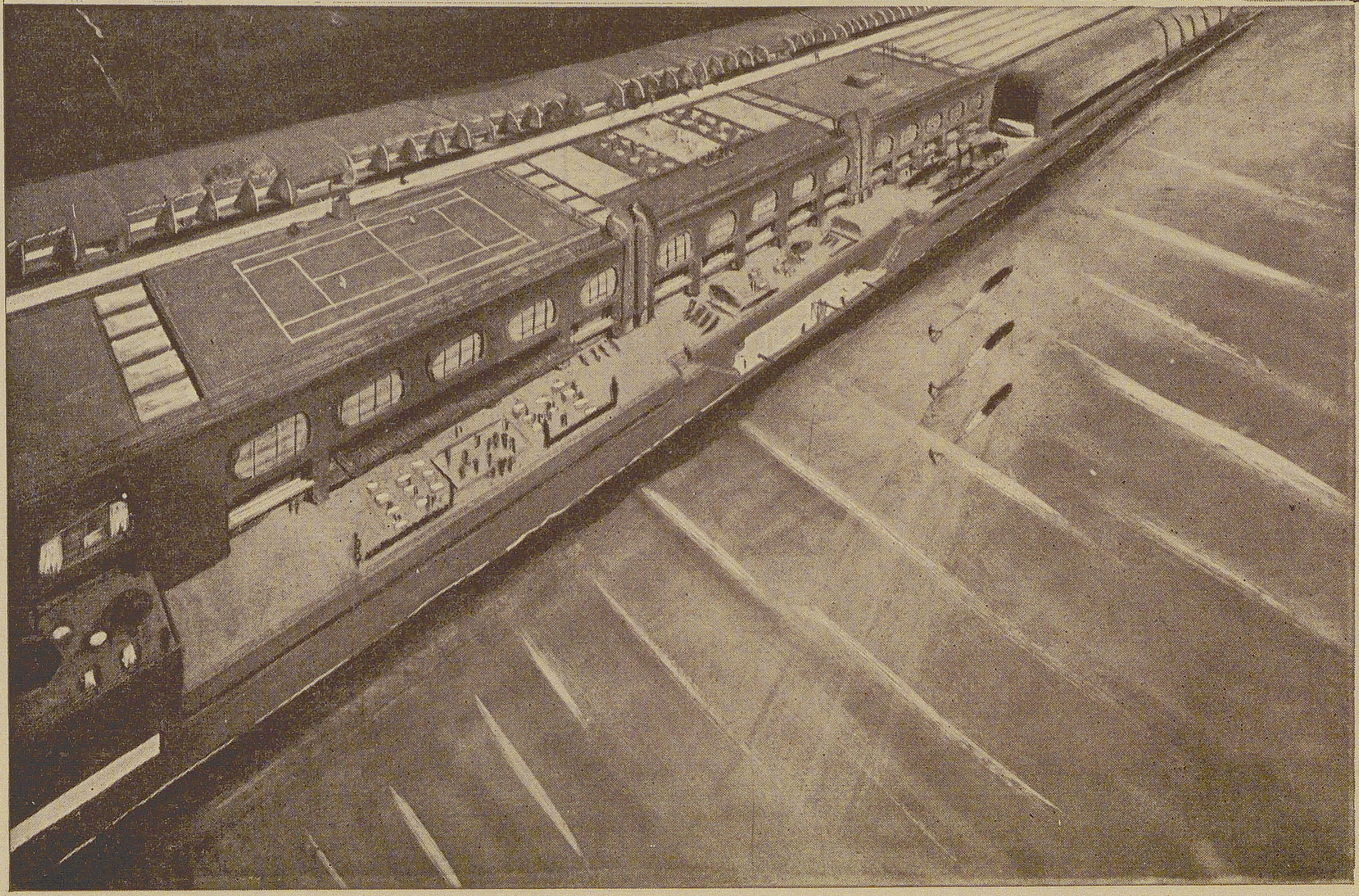

In comparing drawings of the two designs, we see an architect decoupling from the Beaux-Arts tradition of his alma mater and adopting more streamlined, smooth forms in dialogue with the avant-garde. At the level of the plan, the design's initial interior bay, which mimicked the exterior Gothic pointed arch shape, gives way to a more straightforward, rectangular void in the second version (see design renderings above). The reworked launch system, with a predominant ramp by which a trolley cart could raise and move the aircraft to the upper deck for takeoff, provides the guiding logic for the change in the overall shape. Gone are the protruding towers, domes, symmetry, and formal hierarchy of the earlier design.

The program, or function, dictates the form in the new version. The hotel zone features open terraces and tennis courts, while the rest of the island's enclosure is replaced with smooth surfaces only interrupted by necessities like the hangar, whose rounded ceiling with skylights efficiently accommodates the larger airplanes.

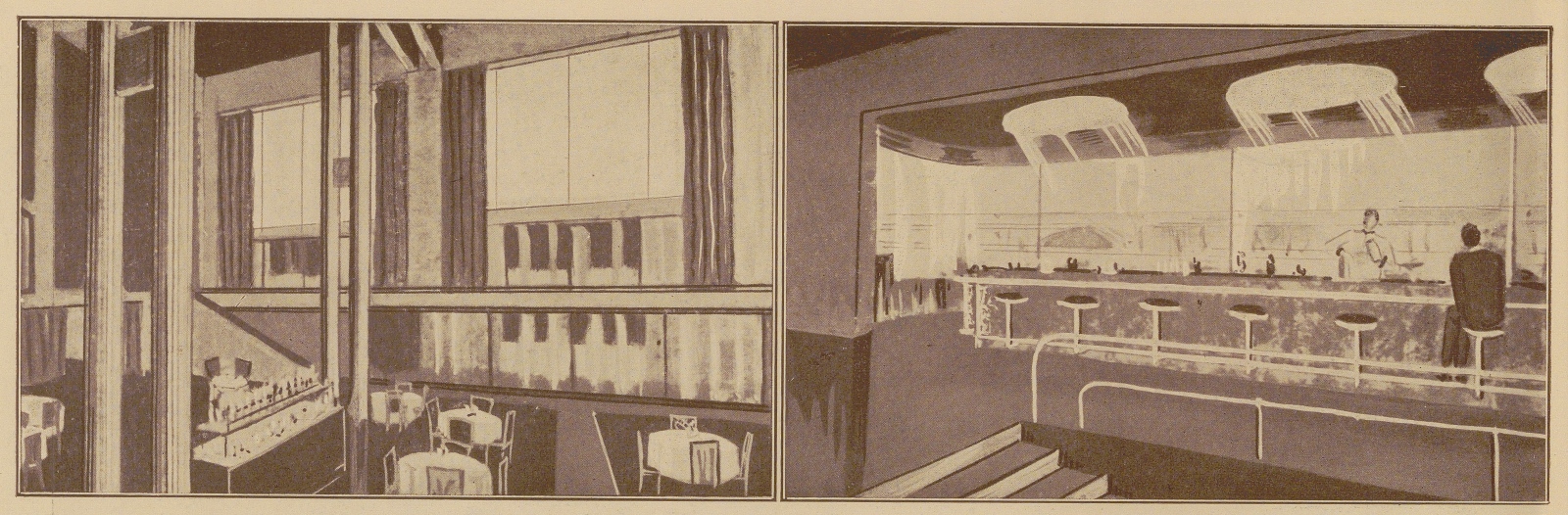

On the interior, the neoclassical domes and rich ornament of the hotel’s salon spaces and the cast-iron frame of its Art Deco dining hall have been replaced with flat concrete planes upheld by reinforced concrete beams in the pool area and thin pilotis (raised columns) supporting a high ceiling in the unadorned, glass-walled restaurant and a bar modeled on American jazz clubs.

An Unbuilt Vision

By the 1930s, seaplanes would give way to land-based airplanes, and the island remained unbuilt. But this little-known project uniquely captures an aesthetic shift in architecture that sought to bring forth a futuristic, streamlined and efficient world.3 By Defrasse’s own assertion, the latter design is more technologically suited to the complexities of sea-faring aviation. However, both versions of the imagined island conformed to the land-based forms of their time while turning their back to the sea. The drawings, paintings, and exquisite plans depict terraces, windows, and amenities that face inward, toward the human-machine drama unfolding in the calm bay in middle of the ocean. This is a sociotechnical imaginary whose success relied on rendering the ocean a mute backdrop so that modern civilization could carry on, unhindered by Earth's geographic scale and natural forces.4 Today, these forces become increasingly difficult to ignore, and the most notable architecture strives to live with the environment rather than close it off.

Endnotes

- Defrasse’s vision was highly ambitious: compare the size of the hotel with the fact that most airplanes in 1924 could carry just two people. However, it was also acutely anticipatory as the industry grew from 6,000 passengers in 1929 to more than 450,000 by 1934, to 1.2 million by 1938. See National Air and Space Museum, "The Evolution of the Commercial Flying Experience," January 3, 2022, https://airandspace.si.edu/explore/stories/evolution-commercial-flying-experience. ↩

- Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, 1986); Le Corbusier, The Decorative Art of Today (London: Architectural Press, 1987). For analysis of the airplane’s influence on Le Corbusier, see M. Christine Boyer, "Aviation and the Aerial View: Le Corbusier’s Spatial Transformations in the 1930s and 1940s," Diacritics 33, no. 3/4 (2003): 93–116. ↩

- See K. Michael Hays, Modernism and the Posthumanist Subject: The Architecture of Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Hilberseimer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992) for how Modernist architecture engaged with changing subjectivity in accordance with industrial capitalism. ↩

- On sociotechnical imaginaries, see Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim, Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015). ↩

About the Author

Katarzyna Balug, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Architecture in the College of Communication, Architecture, and the Arts at FIU. She is a historian of modern and contemporary architecture. Her research explores feedback loops between techno-political change and subjectivity as mediated by architectural experiments. Balug’s writing been published in, among others, Geoforum, Critical Sociology (co-authored), and the edited volume NASA in the American South (University Press of Florida). She holds a Ph.D. in Architecture from Harvard University and was previously a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.