October 7, 2025

By Caroline Crutsinger-Perry, Kress Interpretive Fellow

This Halloween, The Wolfsonian celebrates 100 years of Art Deco with a spooky twist: Dark Deco.

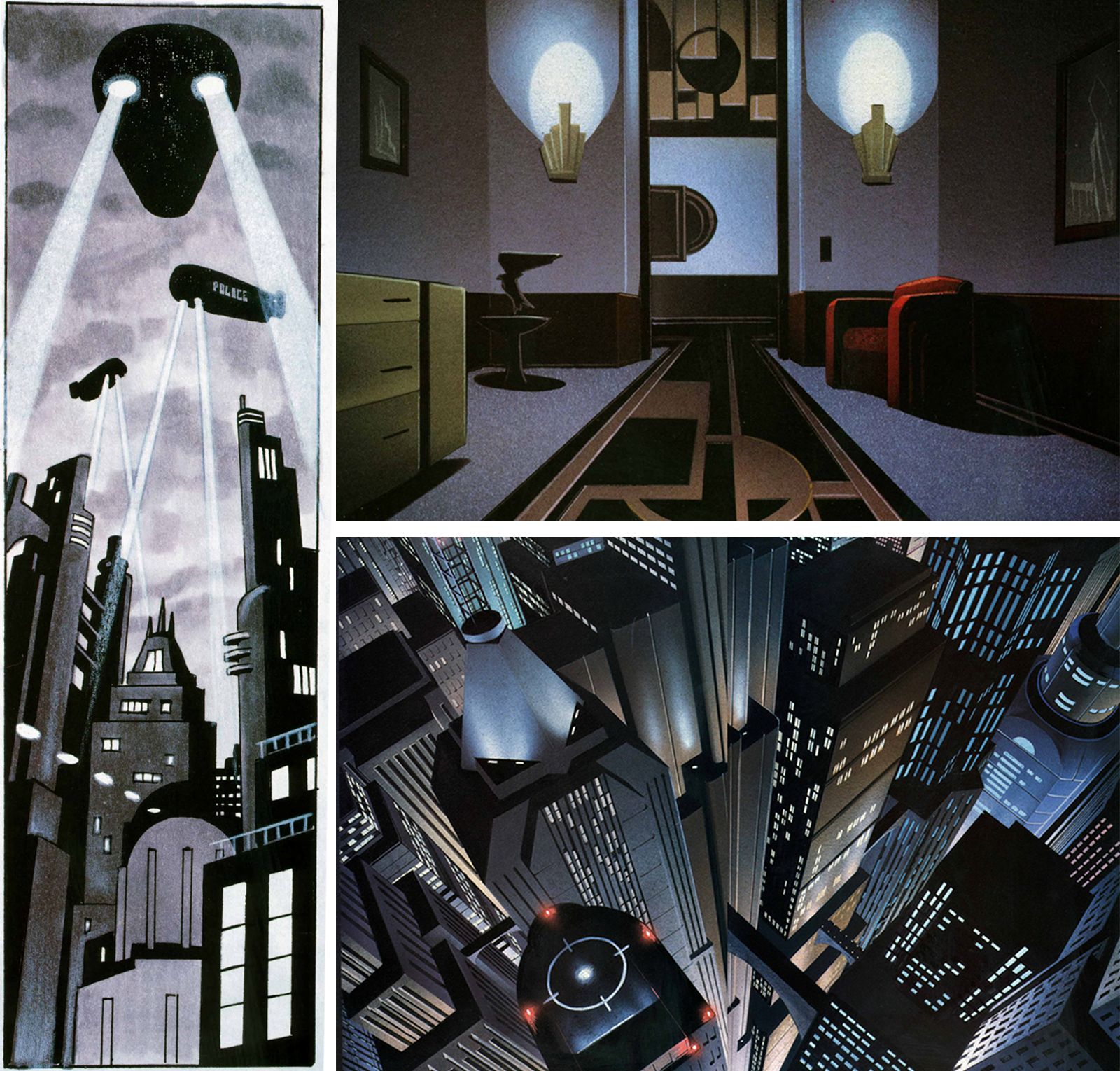

Coined by co-producers Eric Radomski and Paul Dini to describe the shadowy, brooding atmosphere of the 1992 Batman: The Animated Series, "Dark Deco" captured Gotham's tall, angular Art Deco buildings, darkly lit settings, and lavish color schemes. Dark Deco is not a formal style, but rather a striking lens for looking at Art Deco. When do geometry and ornament cross the line into the sinister and uncanny?

Inspired by the Batman aesthetic, we're highlighting four Wolfsonian collection items that embody Dark Deco.

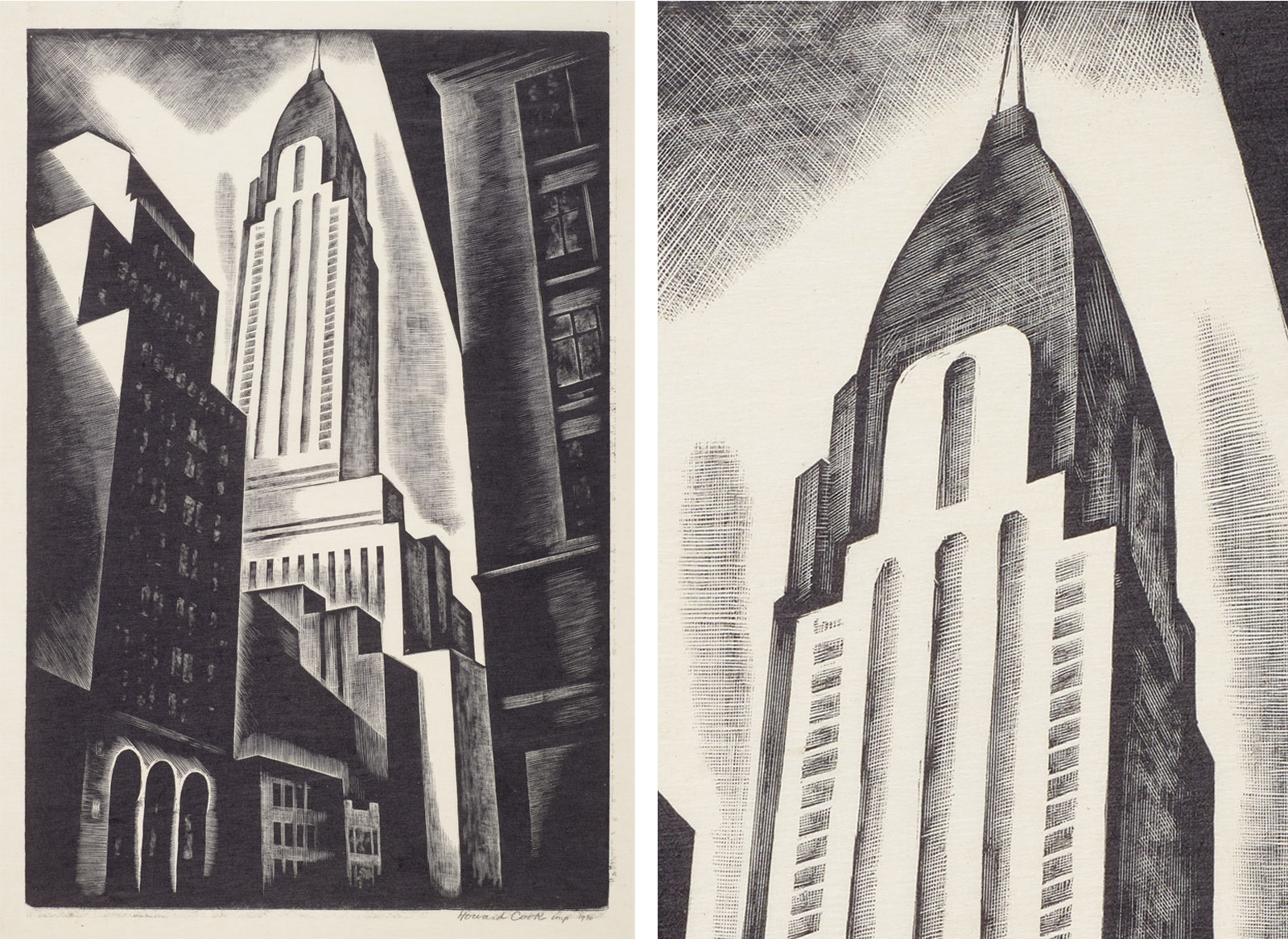

The Chrysler Building: Real-Life Gotham

This wood engraving print of the Chrysler Building in New York City represents many of the characteristics of Dark Deco. Seen from the ground, this perspective of the skyscrapers emphasizes the city's height and angularity, a stylistic technique also used by the creators of Batman: The Animated Series.

Art Deco style drew heavily on Egyptian and Mesopotamian architecture, reflecting a larger cultural interest in ancient civilizations during the early 20th century. The top of the Chrysler Building features several tiers, which were partly inspired by the architecture of Mesopotamian ziggurats. This architectural feature, called telescoping, increases sunlight on the streets and sidewalk below. Note the dark shadows streaming down the sides of the buildings. The geometry of the buildings and the dramatic lighting obscure what—or who—could be lurking just out of sight.

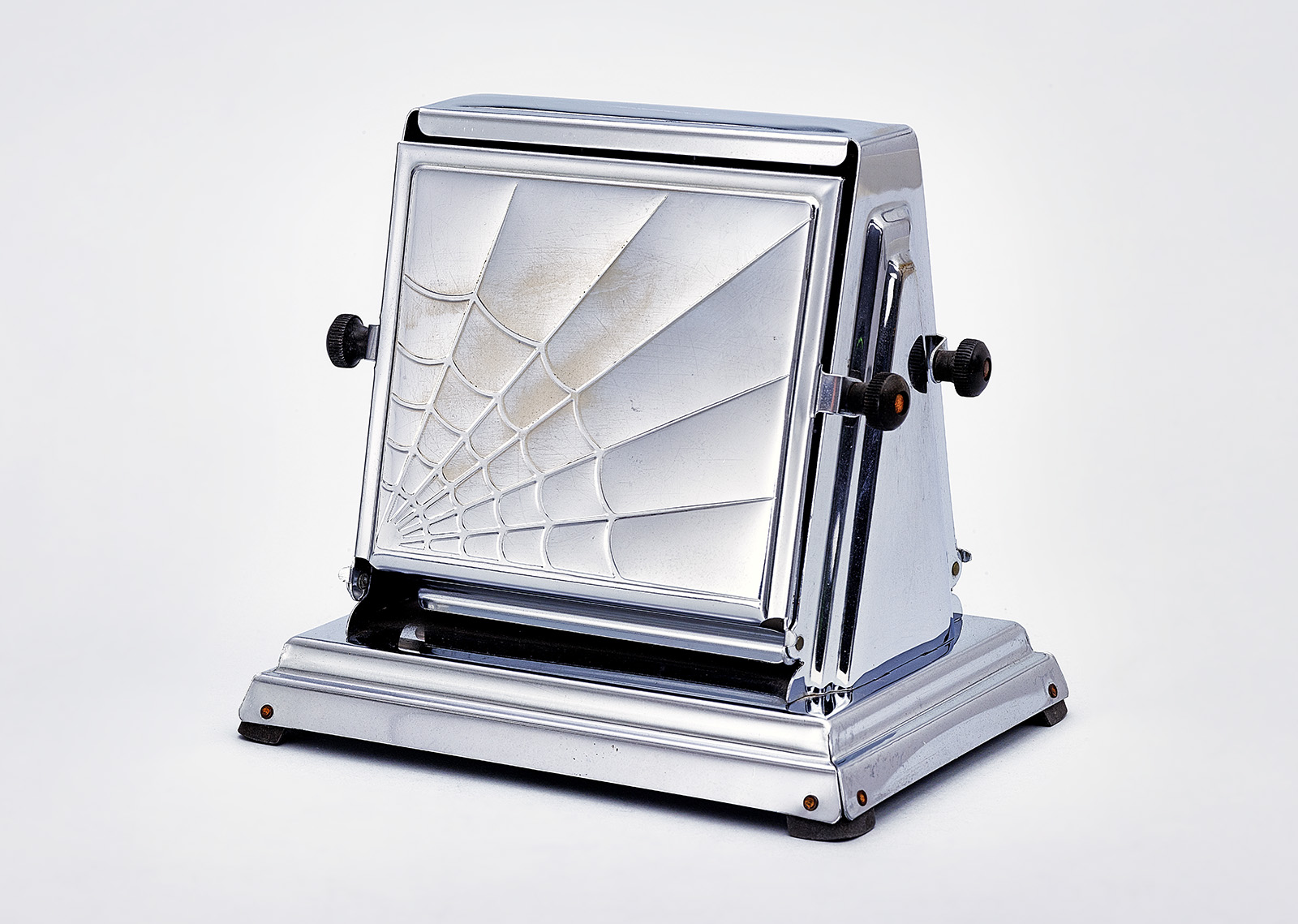

Spiderweb Toaster: A Not-So Crumby Idea

Typically, a spiderweb in the kitchen is cause for concern. But this General Electric Company toaster is the perfect mix of art and function—a key characteristic of Art Deco. The geometric design likens the high-quality craftsmanship of a GE toaster to the strength and precision of the spiderweb's structure. The spiderweb motif has been used more broadly throughout art and history to represent themes from interconnectedness and wisdom to mischief. Let's just hope it doesn't symbolize burnt toast.

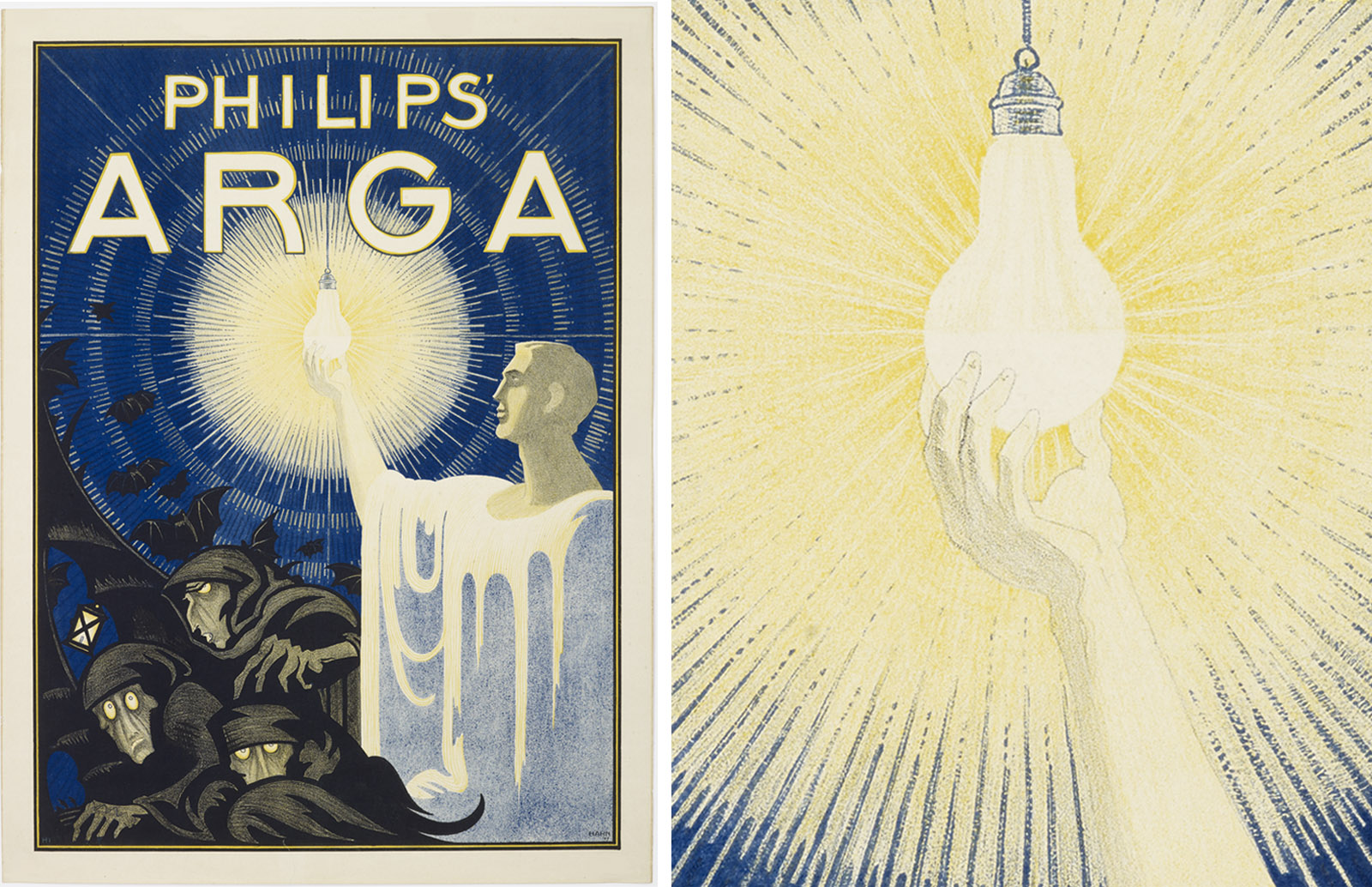

Philips' Arga: Blinded by the Light

In this stylized Art Deco advertisement, a halo of warm light floods the scene. Philips' new lightbulb—outlined by a sunburst motif, symbolizing modern progress—scatters a group of sun-sensitive vampires, which morph into bats and vanish into the dark blue background. The winged creatures in flight do more than add spook to this poster; their absence signals a cleaner, brighter future illuminated by electrification.

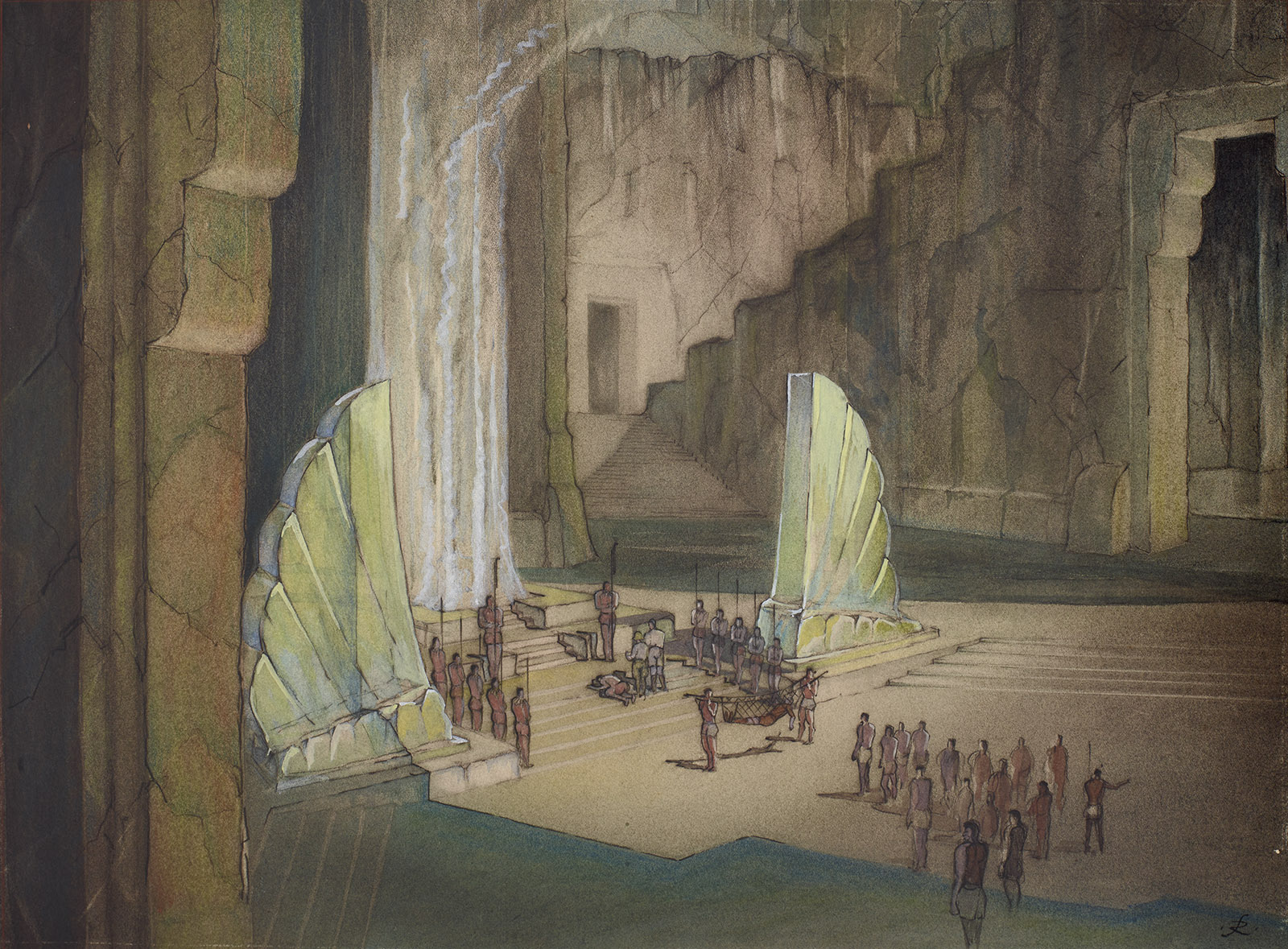

She Design Drawing: Empire of the Imagination

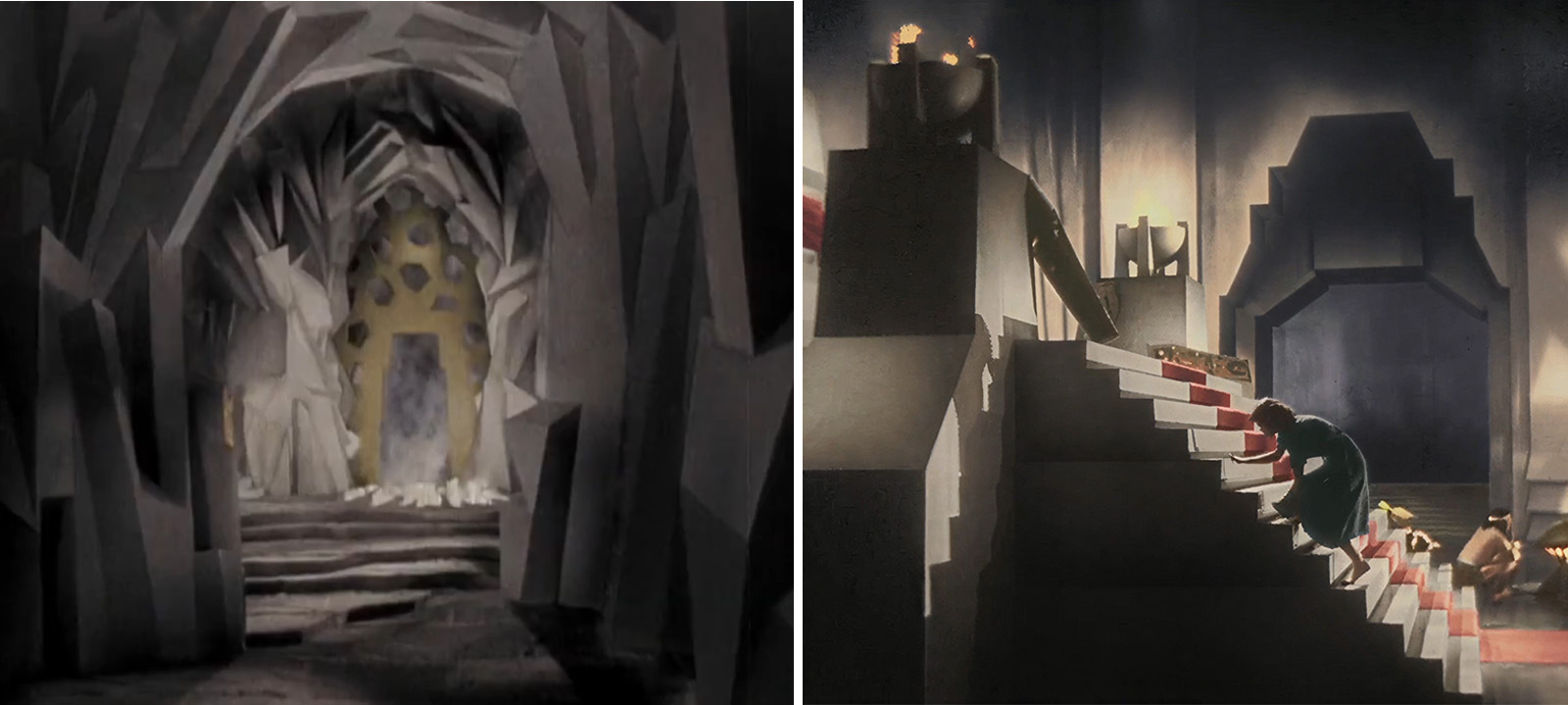

Robert Doulton Stott created this set design sketch for the 1935 film She. In the film, a group of explorers stumbles upon the underground empire ruled by a leader simply known as "She." Within the series of caves and caverns, danger looms for the explorers as they encounter terror, mystery, and the price of immortality.

While the actual film set looks different than the original set design, both versions showcase Art Deco and Egyptian architectural influence. A staircase leads to a throne where the underground ruler awaits, flanked by symmetrical rock formations and entranceways. Stepped details and carved doorways show elegance and opulence, echoing the grandeur and optimism of the early 20th-century design.

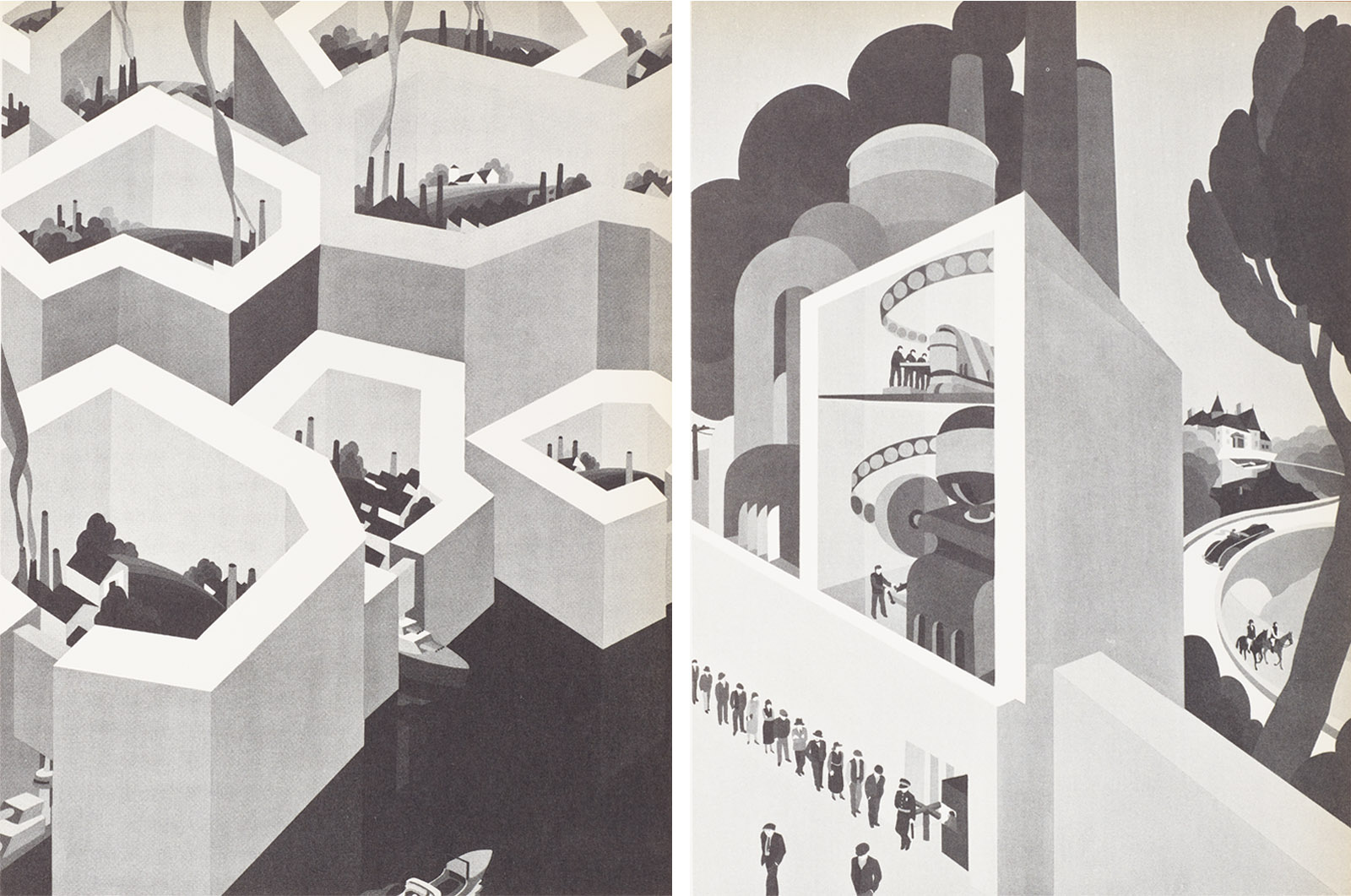

John Vassos Illustrations: Oh, the Humanity!

In the 1935 book, Humanities, John and Ruth Vassos tackle what they believe to be the largest problems facing humankind, such as overdependence on machines and isolation. In the illustration The Machine, Vassos points out that mechanical innovation has freed many people from hard manual labor, while also limiting the distribution of wealth to the elite. Another of his images, Frontier, shows countries as separate entities, cut off from each other by large, thick walls. The use of geometric shapes and lines in these illustrations create division—between the poor and wealthy, and between "us" and "them."

The Machine and Frontier get at many of Dark Deco's themes, from visual style, including dramatic shadows and geometric patterns, to depictions of societies that blur the line between good and evil. Art Deco—and Dark Deco—seamlessly blend art with influences from technology and culture.

Want more Dark Deco? Trick or treat yourself to a Sunday at The Wolfsonian for our third-annual Howl-O-Ween program! Crafts, cookies, and costumes, oh my! It'll be wicked fun.

About the Author

Caroline Crutsinger-Perry joined The Wolfsonian in 2025 as a Kress interpretive fellow. She's passionate about making art history accessible and relatable for visitors.