January 27, 2025

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian and Curator of Library Collection

Few figures in American history rival William Randolph Hearst for audacity. A media mogul, political aspirant, and avid collector, Hearst left an indelible mark on journalism and American culture. The Wolfsonian Library's latest installation, HEARST: Lampooning the King of Yellow Journalism, focuses on Hearst's career and political ambitions, largely through the lens of his detractors.

But beyond the scope of this show lies another compelling chapter of Hearst's legacy: the construction of his palatial, secluded residence in San Luis Obispo County, California. For nearly 30 years, Hearst worked closely with California architect Julia Morgan to design and decorate his "castle." Fortunately, the Wolfsonian collection includes some of Morgan's original designs and tile work from the estate, offering a unique look at one of America's most extravagant landmarks.

La Cuesta Encantada

In 1919, Hearst was poised to embark on a lavish architectural project. The death of Hearst's mother, Phoebe, brought him his full inheritance, including his family's 250,000-acre property in San Luis Obispo County. Hearst envisioned the estate as a quiet retreat for himself and his companion, actress Marion Davies, and a place for lavish parties and costume balls to entertain Hollywood celebrities brought in by private train or car from Los Angeles or flown into his private airstrip.

Completed in 1947, La Cuesta Encantada (the Enchanted Hill) features the main Casa Grande, inspired by the Santa Maria la Mayor, a centuries-old church in Ronda, Spain. Together with its Casa del Mar, Casa del Monte, and Casa del Sol guest houses, the complex could accommodate scores of guests in its 42 bedrooms, 61 bathrooms, and 19 parlors. Amenities included formal gardens littered with urns and statues; stables and horse-riding trails; indoor and outdoor mosaic-tiled Neptune and Roman Pools; tennis courts; a golf course; a movie screening room; and even the world's largest private zoo. Despite Prohibition, cocktails were regularly served on Saturday evenings in the assembly room, and the castle boasted a well-stocked wine cellar.

Julia Morgan: The Architect

To realize his vision, Hearst turned to Julia Morgan, architect and longtime family associate. Like Hearst, Morgan was no stranger to pushing boundaries. She became the first woman to receive a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley, first to graduate from the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and first to obtain an architectural license in California. In all, she designed more than 700 buildings in the state, several of which are registered historic landmarks.

Morgan's connection to the Hearst family began early in her career. Hired by architect John Galen Howard, Morgan worked on two Hearst-funded projects on the Berkeley campus: the William Randolph Hearst Greek Theatre, inspired by the classical Epidaurus amphitheater, and the Hearst Memorial Mining Building, a Beaux Arts structure built to house the College of Mining.

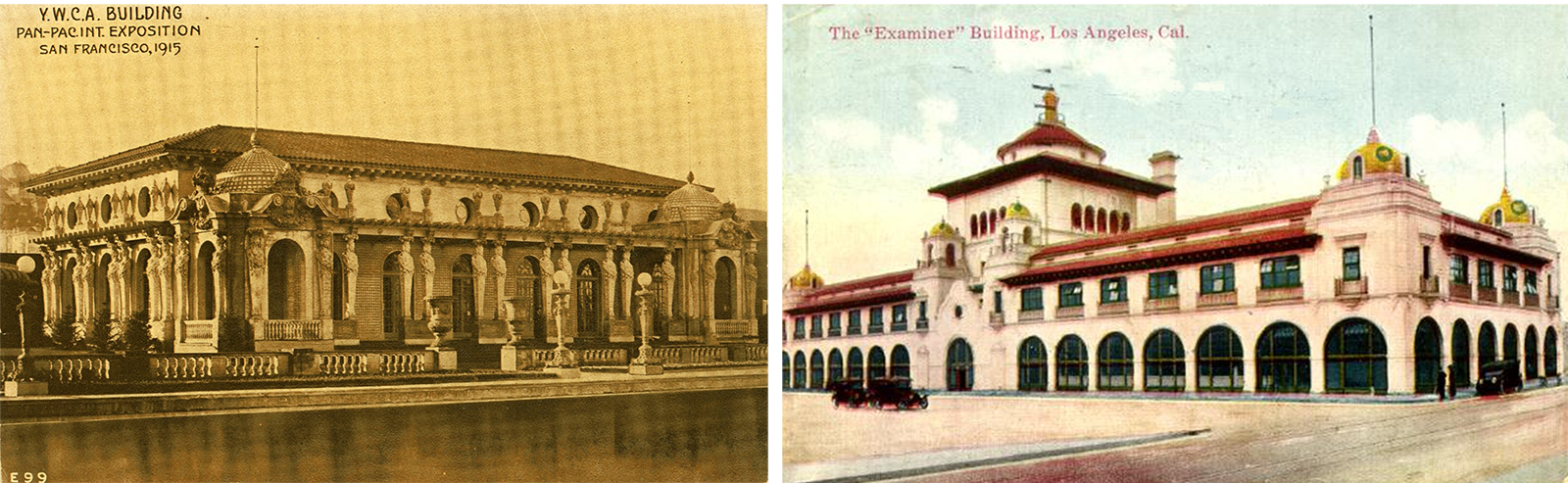

The Hearsts must have been impressed with Morgan's contributions to these early projects because they hired her for several important projects in the following years. Morgan renovated Phoebe Hearst's expansive Alameda County estate and designed a Mission Revival-style structure to house the younger Hearst's Los Angeles Examiner.

Designing a New California Style

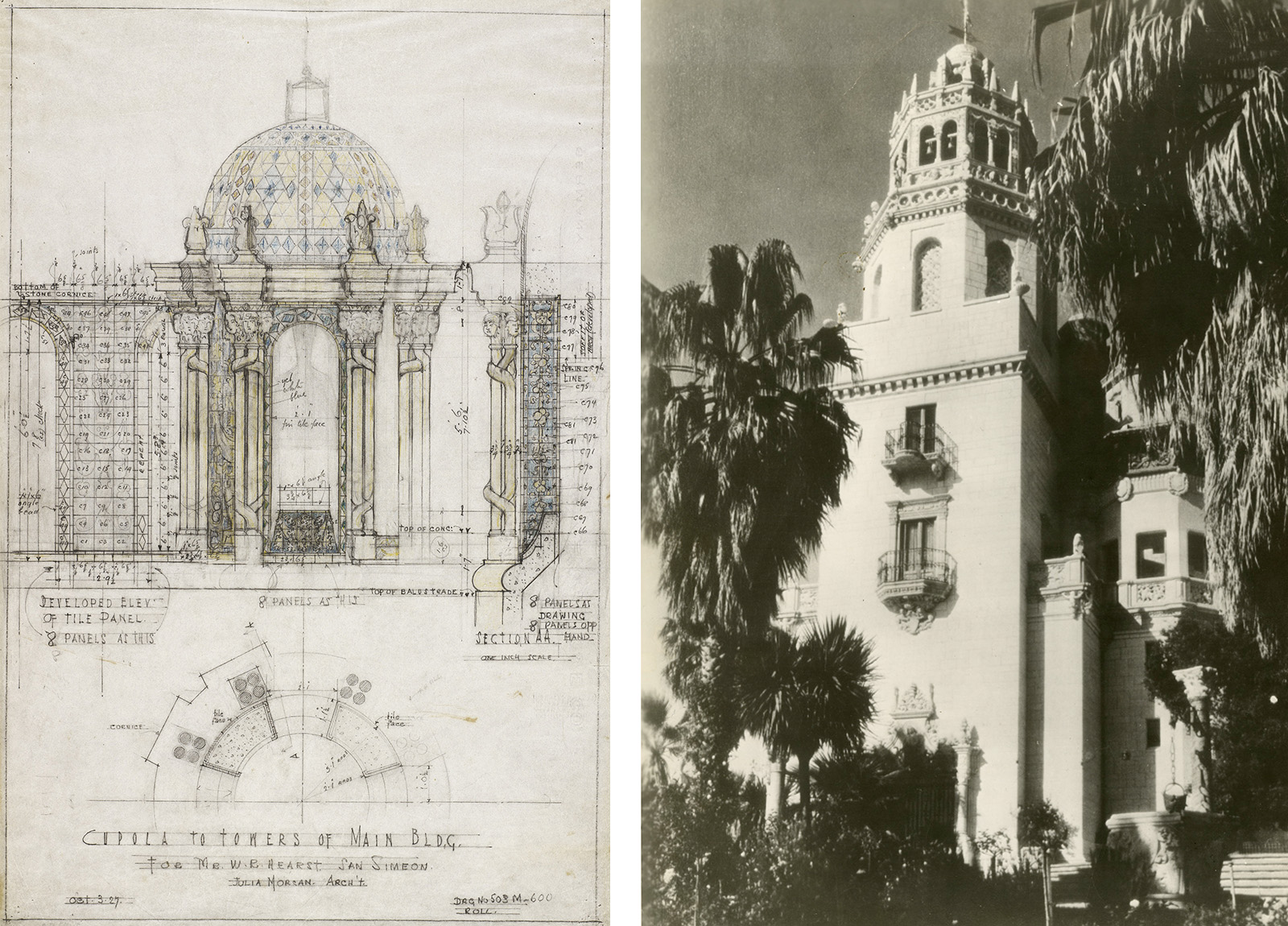

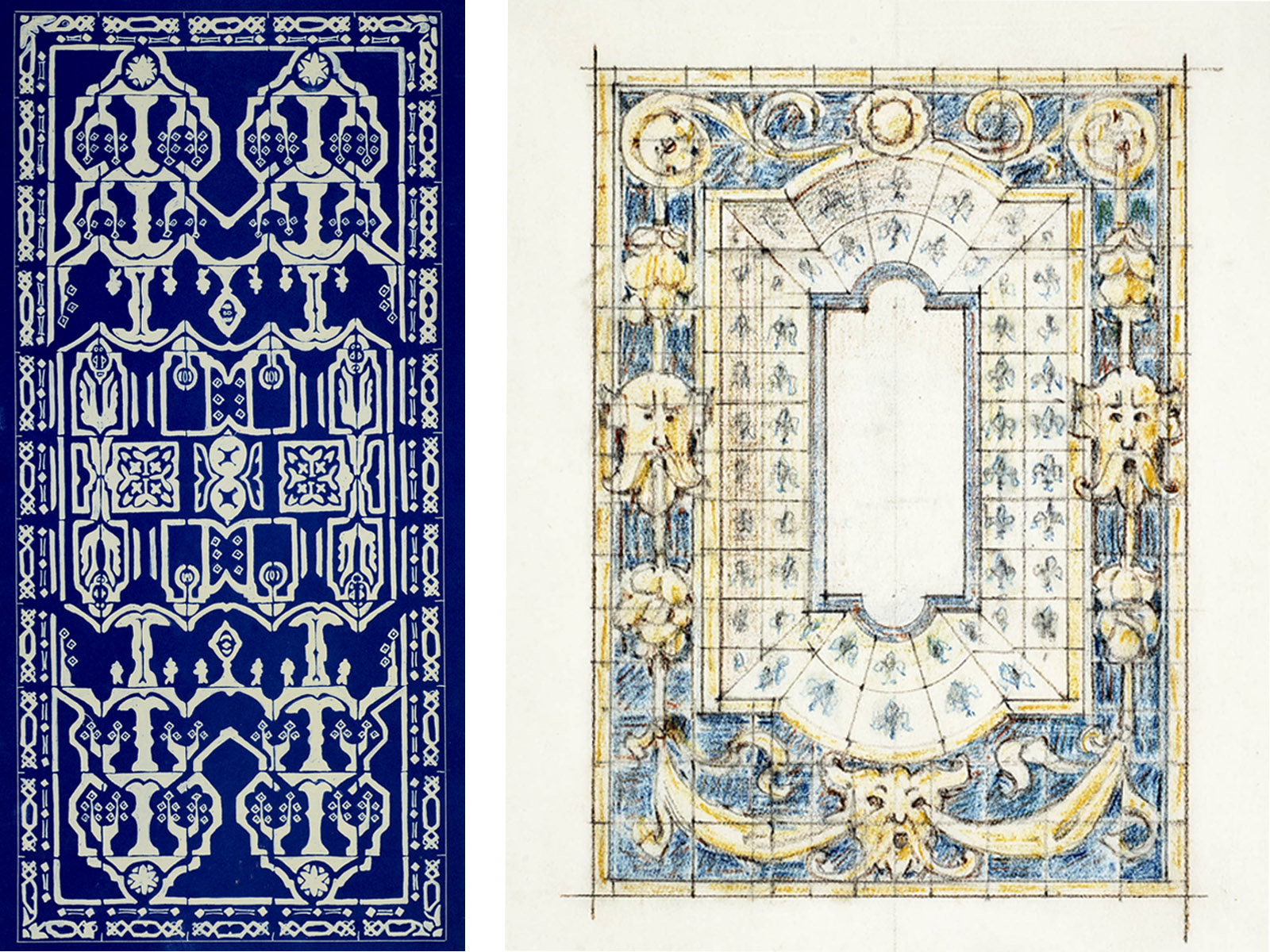

Both Hearst and Morgan shared an interest in shaping an emerging California architectural style: a blend of Spanish Colonial, Mediterranean, and Neoclassical, which Morgan had already tried out several years earlier in her design for the Young Women's Christian Association pavilion at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Morgan's designs for tile decorations, ornaments, and a cupola atop the towers of La Casa Grande, the main building of his San Simeon estate, reflect the same mix of influences.

Ceramic tiles, in particular, not only served practical purposes but also drew inspiration from Spain’s Roman and Medieval Islamic architectural influences, lending an air of pretended antiquity to the 20th-century building. The tiles also added color, symmetry, and a splash of reflectivity that relieved the stark white towers and walls of La Casa Grande, the main building of the San Simeon estate.

Ambition and Excess

Hearst's castle loomed large in the imagination of filmmaker Orson Welles's 1941 film classic, Citizen Kane. Collaborating with screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, a frequent guest at Hearst's San Simeon estate, Welles created a thinly disguised drama exposing the private life of the acquisitive media mogul. In the film, Orson Welles uses exterior shots of Oheka Castle in Huntington, New York, to represent the protagonist, Charles Foster Kane's "Xanadu" mansion and formal gardens. To underscore Welles's critique of the protagonist's excessive collecting habits, the film devotes an entire scene to detailing Kane's palatial estate—which bears a striking resemblance to Hearst castle—describing it as "a collection of everything so big it can never be cataloged or appraised; enough for ten museums; the loot of the world."

By the time the film was released, the media mogul's unchecked spending saddled him with more than $125 million in debt, forcing him to sell off some of his unprofitable newspapers, relinquish control of his media empire, and auction off much of his collection of art and antiques. Despite such losses, Hearst continued to retain and live in his secluded San Simeon estate until old age and ill health forced him to relocate to Beverly Hills. Years after Hearst's death in 1951, the Hearst Corporation donated the castle and grounds to the state of California, where it has become a popular, publicly accessible house museum, state park, and registered National Historic Landmark.

Visit HEARST: Lampooning the King of Yellow Journalism in The Wolfsonian's 3rd-floor gallery through March 2, 2025.