November 4, 2024

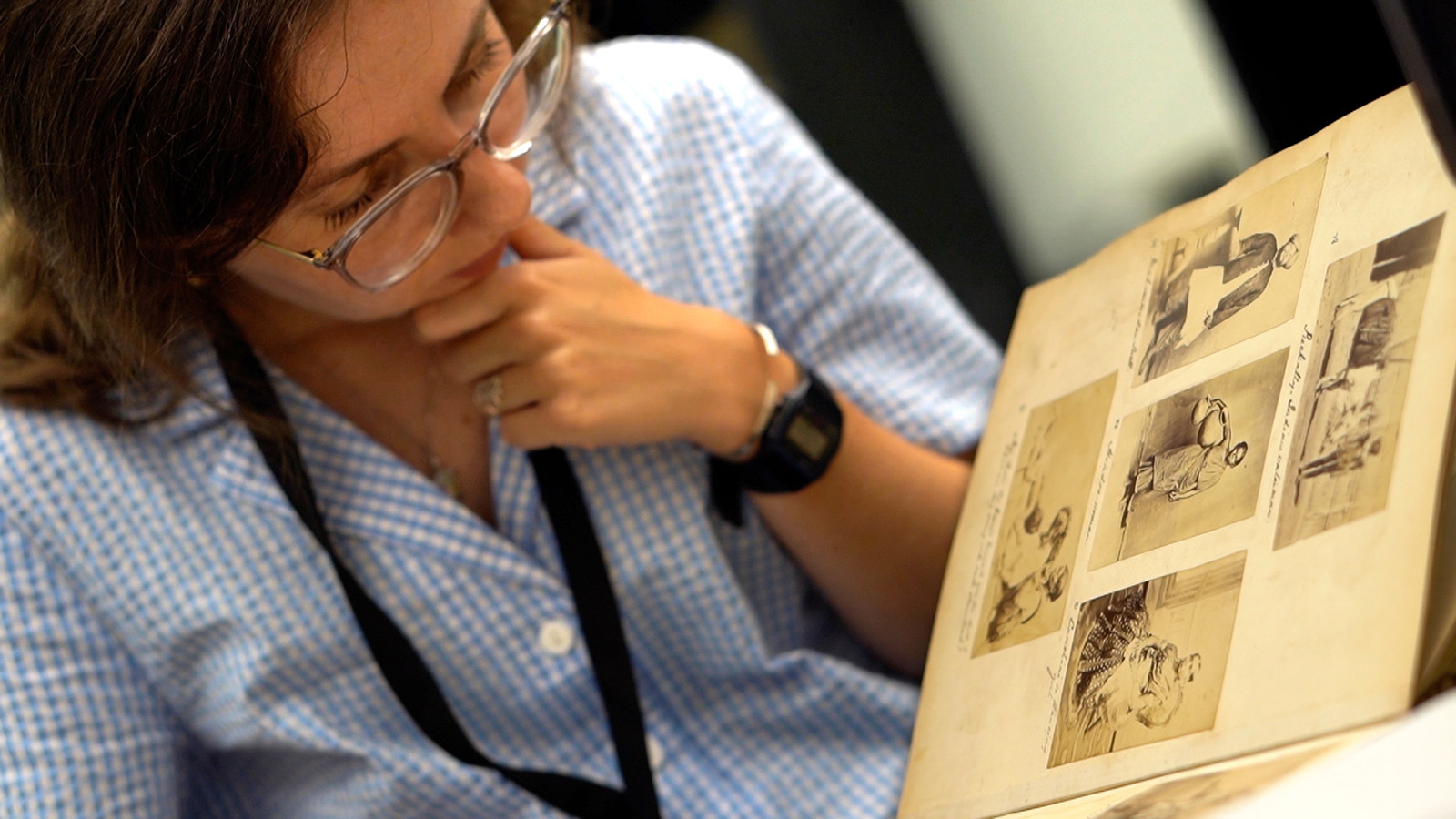

Family photo albums, once a staple in every household, may be tucked away in attics or closets alongside collections of CDs, road maps, and landline phones. Yet, despite the shift towards sharing images on social media and group chats, these albums are too precious to discard, capturing a family's most important moments: weddings, anniversaries, birthdays, and vacations. Occasionally, they make their way into a museum collection or archive, where they carry important contextual clues about their makers—many times filling in gaps that other surviving text-based documents and archives can't speak to. For historian and researcher Ellen Smith, photo albums from the Wolfsonian collection became a treasure trove for learning and helped bring history to life.

A postdoctoral researcher in historical studies at the University of Bristol, Smith spent three weeks over the summer as a Wolfsonian research fellow in the library, exploring items from the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection. Her research focuses on Britain's colonial rule over South Asia during the 19th and 20th centuries. With a keen interest in personal ephemera from this era, Smith searched these materials for alternative histories often omitted from traditional historical narratives.

– Molly Channon, interpretation specialist

Interview with Ellen Smith

Molly: I have to know—did you make scrapbooks when you were little?

Ellen: I had scrapbooks; I had diaries. And I made albums with photos, drawings, and multimedia. So yeah, I kind of know the process and the work that’s involved. It takes a lot of time and effort to sit down and paste the images, write captions, organize them, assemble them, draw them.

Molly: We're looking at an album belonging to Rodney Foster, a British army officer born in India in 1882. This is one of several albums made by Foster and his daughter, Daphne, documenting colonial life in India. How do these images align with what we know about British families in India at the time? Anything surprising to you?

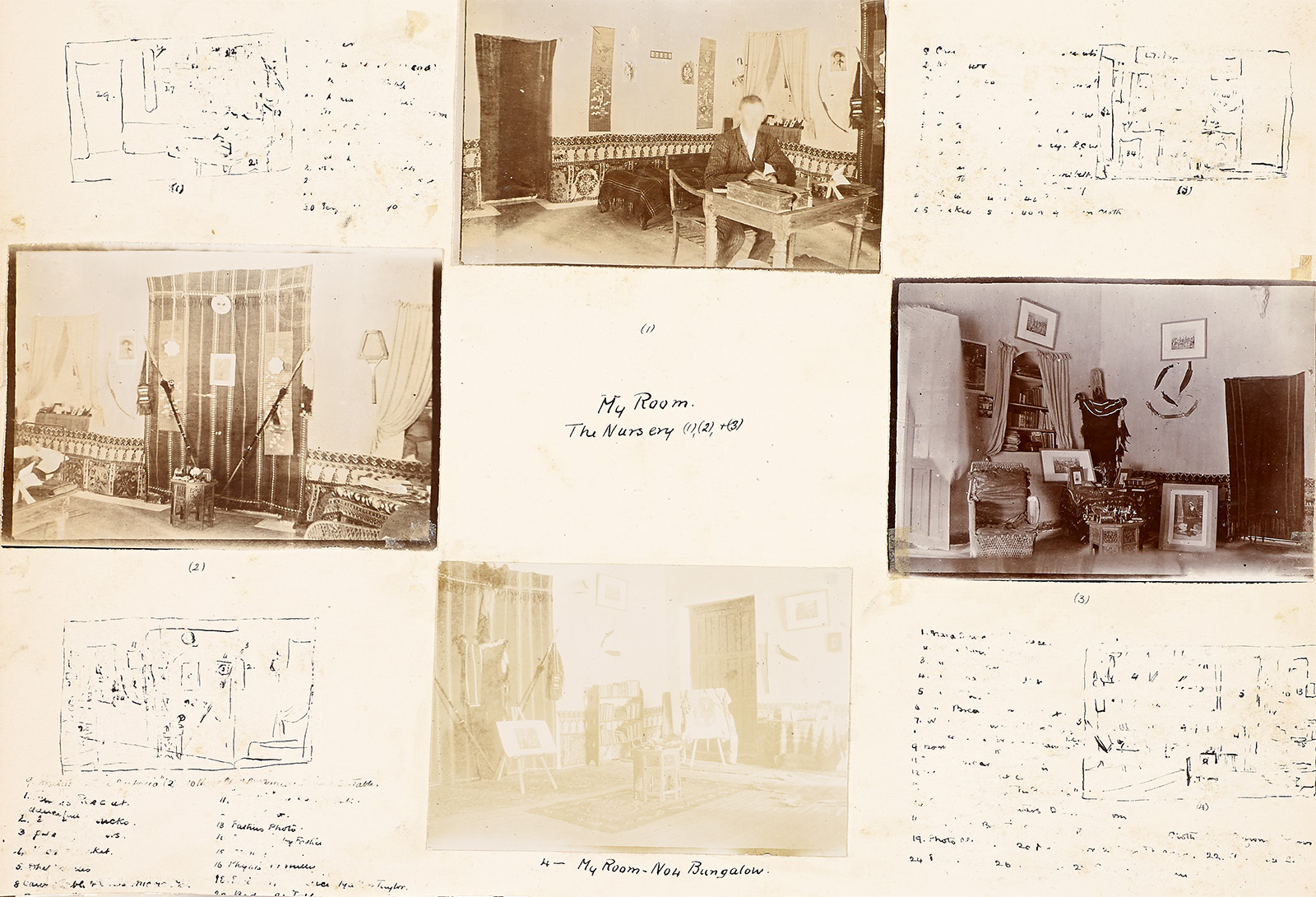

Ellen: A lot of the images resonate with what we might expect of an army official's life, but some of the photographs don't. It’s unusual, for instance, to see unposed pictures from the Victorian or Edwardian era with people just enjoying themselves in India, but here the officer documents his life in extreme detail, capturing everything from his land surveying trips to casual moments at home with his family and pets.

Molly: What else stands out to you in the album?

Ellen: Another spread has a picture of "nautch girls," Indian female dancers admired by both the British and Indian communities. On another spread, there's a photograph of two British women dressed in similar attire. At the time, British women were fascinated by the perceived freedoms of some Indian women, perhaps including these dancers.

Molly: Why are we seeing so many photos of memorials?

Ellen: Rodney Foster seems to be going on what we might call the "mutiny circuit" or trail, which involved British people traveling around the subcontinent, taking images and paying their respects to monuments and memorials commemorating British people who died either in war or in local rebellions. Some of the sites Rodney visited are related to significant revolts, such as the 1857 Indian Rebellion and even the less commonly known Manipur Rebellion in 1891, which is shown here.

The Manipur kingdom had had enough of British interference in their affairs, and they rose up and executed British officers who were stationed there. The British launched a counter-expedition against them. This rebellion is proof that local people were resisting and were not passive, something that has historically been glossed over. What I'm curious about here is why Rodney documents the monument and finds it significant.

Molly: Taking a step back, how do photo albums like this inform your understanding and insight about this history? These people?

Ellen: I'm fascinated by what visual culture and objects—crafted by ordinary people—can tell us about their makers. What can they reveal that text can't? Personal photographs reveal a lot. They offer a snapshot of everyday life, showing aspects that text alone doesn't capture.

At the same time, images can be very constructed. For example, Rodney documents his home interiors, including his office and bedroom, with both photographs and hand-drawn sketches in painstaking detail, perhaps to record those spaces for his future self or to share with others. For us, these materials provide unique insights into his personal world and living conditions, including his apparent interest in tribal weapons and military memorabilia.

Molly: We often overlook personal scrapbooks and photograph albums as being valuable in the same way as official documents. What is the value of preserving these materials in a museum collection?

Ellen: A lot of historians rely on official documents and national archives. But firsthand materials like family albums and scrapbooks add texture and present alternative accounts of leading historical narratives. And given the time and effort the Foster family put into their albums, it seems clear that they were collecting, archiving, and narrating their experiences for future historians and descendants. So I'm leaning into it.

Molly: So, what's next for your research?

Ellen: I'm working on publishing all my research! I've made exciting findings that I want to share with broader audiences. My next journal article speaks to practices of reading, writing and publishing personal papers from India during the 1857 Indian Rebellion, and my time in Miami has cemented so many of my ideas for this. Many thanks to the Sharfs for their avid collecting efforts!