April 29, 2024

By Quinlan Smith (FIU class of 2024), IDEAL interpretation intern

April 29, 2024

By Quinlan Smith (FIU class of 2024), IDEAL interpretation intern

Souvenir ball, c. 1893

From the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition

American Enterprise Co., publisher

Brass, ink, paper

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, 86.19.310

Extravagant. Colossal. Magnificent.

Such words describe the awe-inspiring atmospheres of 19th and 20th-century world's fairs, which attracted millions of curious fairgoers during their months-long runs. The international expositions were famous for their size and immense cost but were also designed to be impermanent, with elaborate grounds and buildings often disappearing after their close, creating a need for tangible forms of remembrance for these ephemeral events. One unique piece of memorabilia from the Wolfsonian collection, a brass souvenir ball housing an accordion-style informational pamphlet, provides a rare window onto the buildout of a particularly revolutionary, and distinctly American, world's fair: the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, or World's Columbian Exposition, famous for its spectacle, scale, and style.

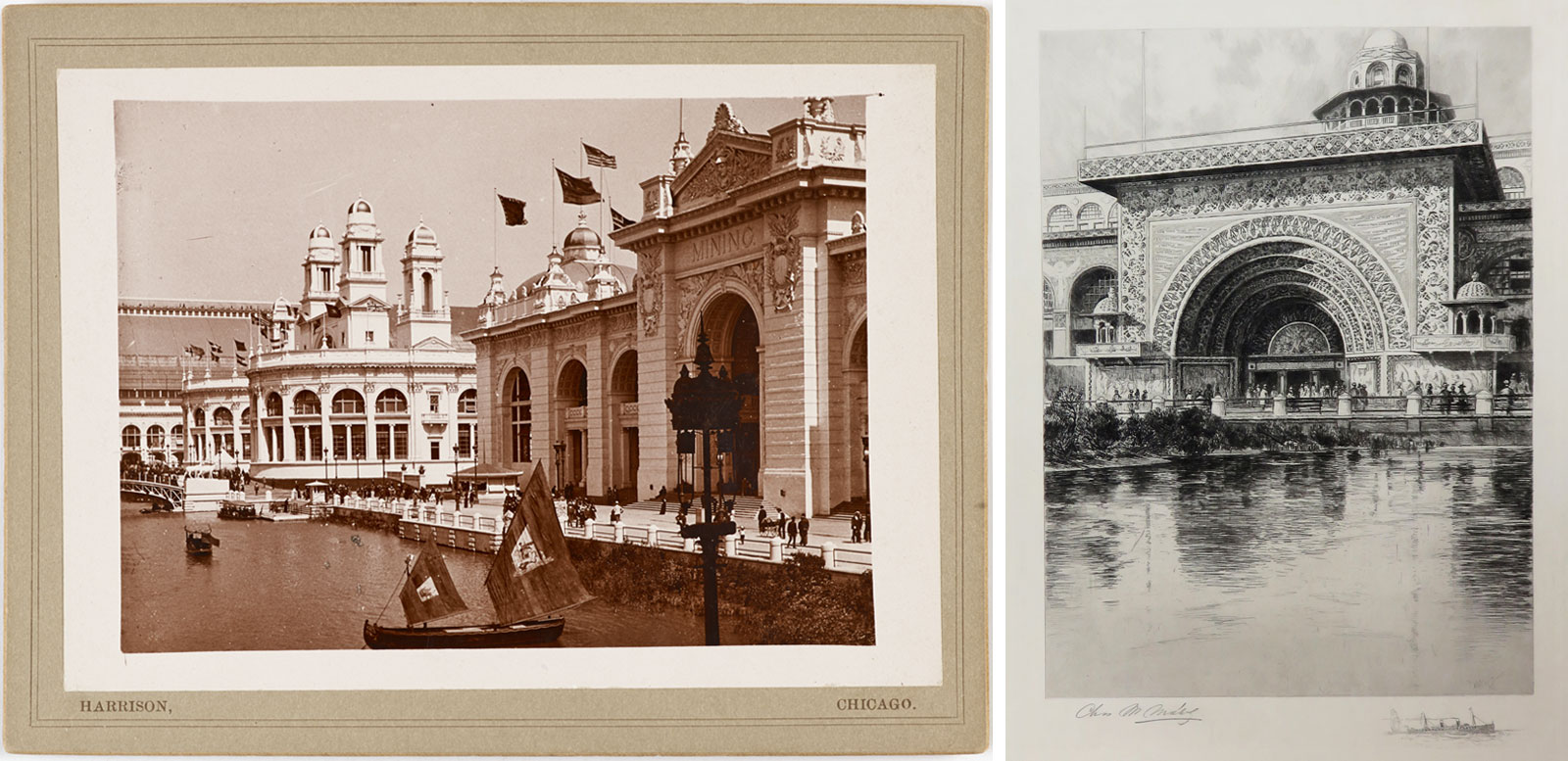

The ball and its pamphlet begin with a portrait and biography of Christopher Columbus, the figurehead of the fair, which was held on the 400-year anniversary of his voyage to the Americas and kicked off by replicas of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria sailing across the Atlantic. While the exposition patriotically touted American exceptionalism and promoted the up-and-coming city of Chicago, it was meant to bridge Eurasia and the New World by showcasing culture and technology from 46 nations around the globe. Notable non-U.S. elements included a full-scale replica of a German village and an international market/walkway on the Midway Plaisance, where many Americans were introduced to Egyptian belly-dancing.

The rest of the pamphlet features illustrations and information about the fair's 14 main buildings, which contained exhibits on a wide variety of themes ranging from manufacturing, machinery, and agriculture to horticulture, forestry, and fishery. Text describes each structure's focus, attractions, footprint, and, in some cases, even its cost. Wealthy Chicago capitalists, who had competed against New York City financiers such as J. P. Morgan to host and fund the fair, spared no expense—of the astounding $28 million operating budget, $18 million (more than $600 million today, adjusted for inflation) was allocated solely for the construction of the temporary buildings.

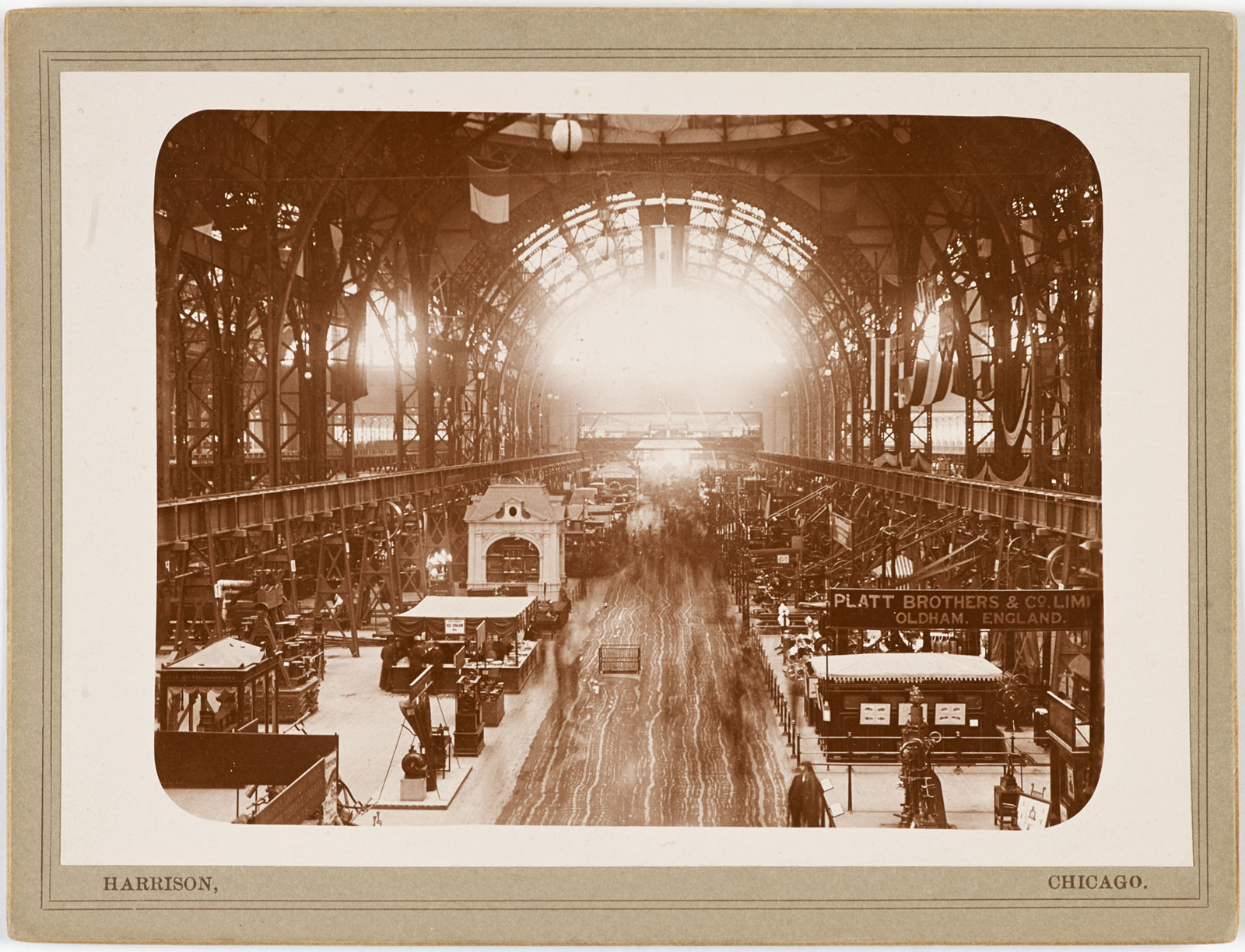

To get a sense of their massive scale, take for example the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. Described within the souvenir ball as a "mammoth structure covering 31 acres" and housing 86 separate galleries, this building, if still standing today, would be one of the ten largest in the world by square footage. Or the Machinery Hall, tall enough to include an "elevated traveling crane" providing the ability to transport heavy machinery from one side of the hall to the other. As quoted in the souvenir ball, the Machinery Hall—"the greatest display of machinery ever grouped together within a single building"—cost $1.2 million to construct, the equivalent of around $40 million today.

Dramatic and vivid descriptive texts in the ball's pamphlet help bring to life the experience of the buildings, most of which are long-gone. The Agricultural Building is referred to as "bold and heroic," while the account of the Fisheries Building emphasizes the 220,000 gallons of water necessary for its freshwater and saltwater aquariums and exhibits. The Dairy Building, too, is described as extensive, housing an amphitheater, cold storage rooms, and a school for conducting "tests for determining the relative merits of different breeds of dairy cattle as milk and butter producers."

Of those 14 famous buildings of the world's fair, only one remains: the Palace of Fine Arts, now home to Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry. The rest of the physical footprint of the fair—including the Midway Plaisance and the fair's setting, the lush Frederick Law Olmstead-designed lakefront grounds of Jackson Park—was returned to city officials at the conclusion of the fair to become public space, where visitors today can still find other World's Columbian Exposition relics (a Japanese garden, and the centerpiece of the fair, Daniel Chester French's statue The Republic). Despite their loss, you can still feel the impact of the 14 buildings in Chicago and beyond; their neo-classical architectural style, which earned the fair the nickname of "the White City," is often credited with reviving the classical form in the city and throughout the United States.

As for the souvenir ball itself, its scale is less grandiose—small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, a fitting size for a trinket "intended to interest and instruct children, as well as those of 'larger growth'" (a similar souvenir type appears 40 years later, at the 1933 Chicago World's fair, this time in the shape of a walnut). But its small size contrasts with the personal significance it likely carried. World's fair memorabilia, which ranged from pins and postcards to globes, medals, and mugs, were meant to memorialize a fleeting event and were probably closely cherished by those who attended, especially if they traveled from afar and at great expense. It's not a stretch to imagine that a world's fair might have been the highlight of one's life! And for us today, photographs, contemporary writing, ephemera, and objects like this are some of the only vehicles through which we can experience the fairs from the point of view of visitors eager to commemorate occasions they witnessed firsthand, and would not soon forget.