April 17, 2024

By Silvia Manrique, Assistant Director of Collections

You might be surprised to learn that The Wolfsonian–FIU holds over 200,000 objects in its collection. From early 19th-century European paintings to Second World War-themed Japanese kimonos to the very first radios ever made, the diversity of materials, topics, artists, and origins found in the Wolfsonian vaults is staggering. So are their stories.

Naturally, objects age or get damaged along the way, and some of their history would be lost if not for our determined efforts to preserve them. Sometimes those efforts involve intervening with conservation treatment, but perhaps surprisingly, in most cases it is "preventive care"—like freezing, digitization, and a little bit of mystery-solving—that does the trick.

The Case of the Lost Images

One of the most remarkable holdings in the Wolfsonian collection is an archive of over 8,000 architectural drawings, documents, and photographs produced by the renowned New York City architectural firm, Schultze & Weaver. Between 1921 and 1948, Schultze & Weaver designed many iconic buildings throughout the United States, including New York City's Waldorf-Astoria and Pierre Hotel, Miami's Biltmore Hotel and Freedom Tower, and Los Angeles's Park Labrea Housing Development—one of the largest and one of the first integrated apartment complexes in the country.

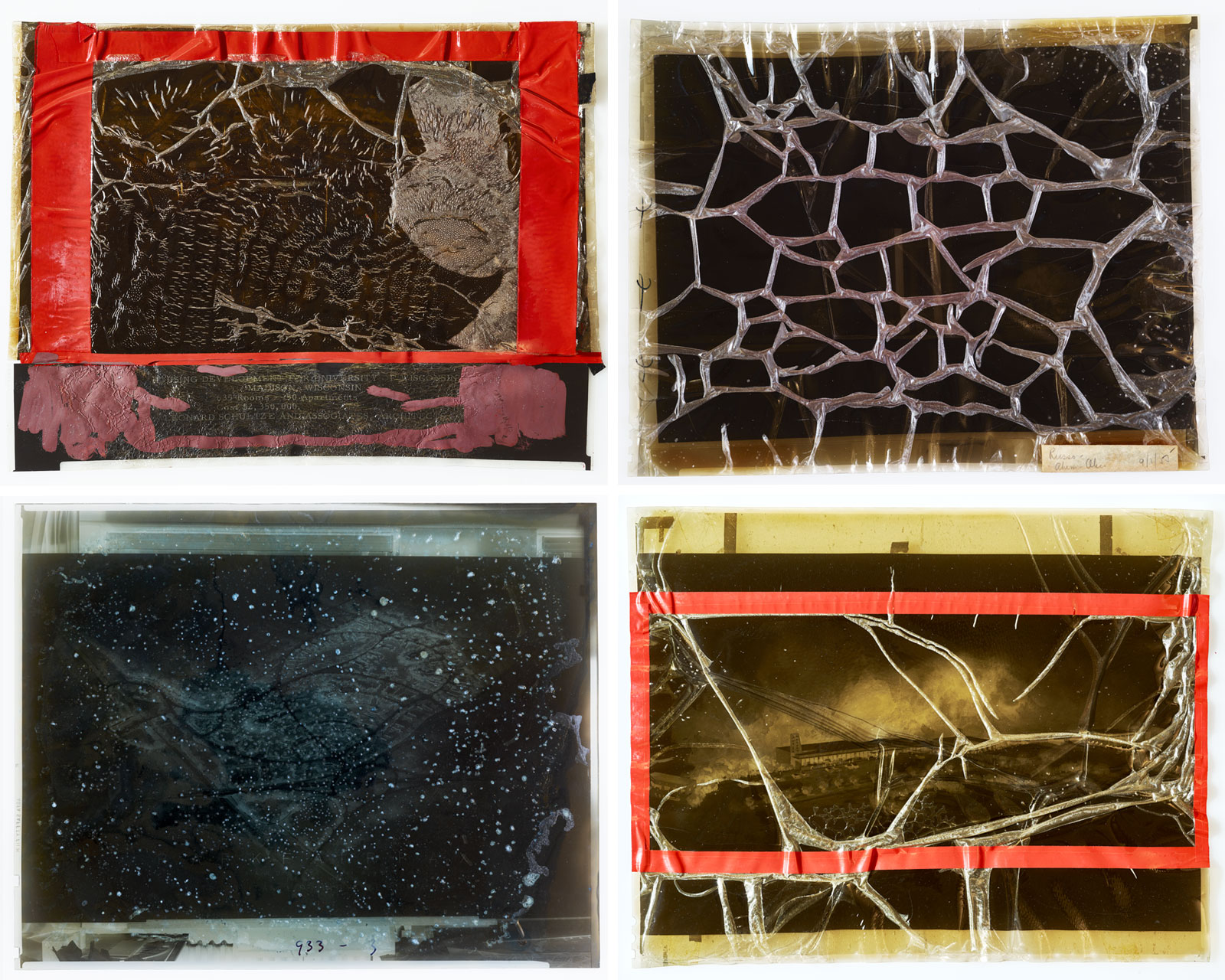

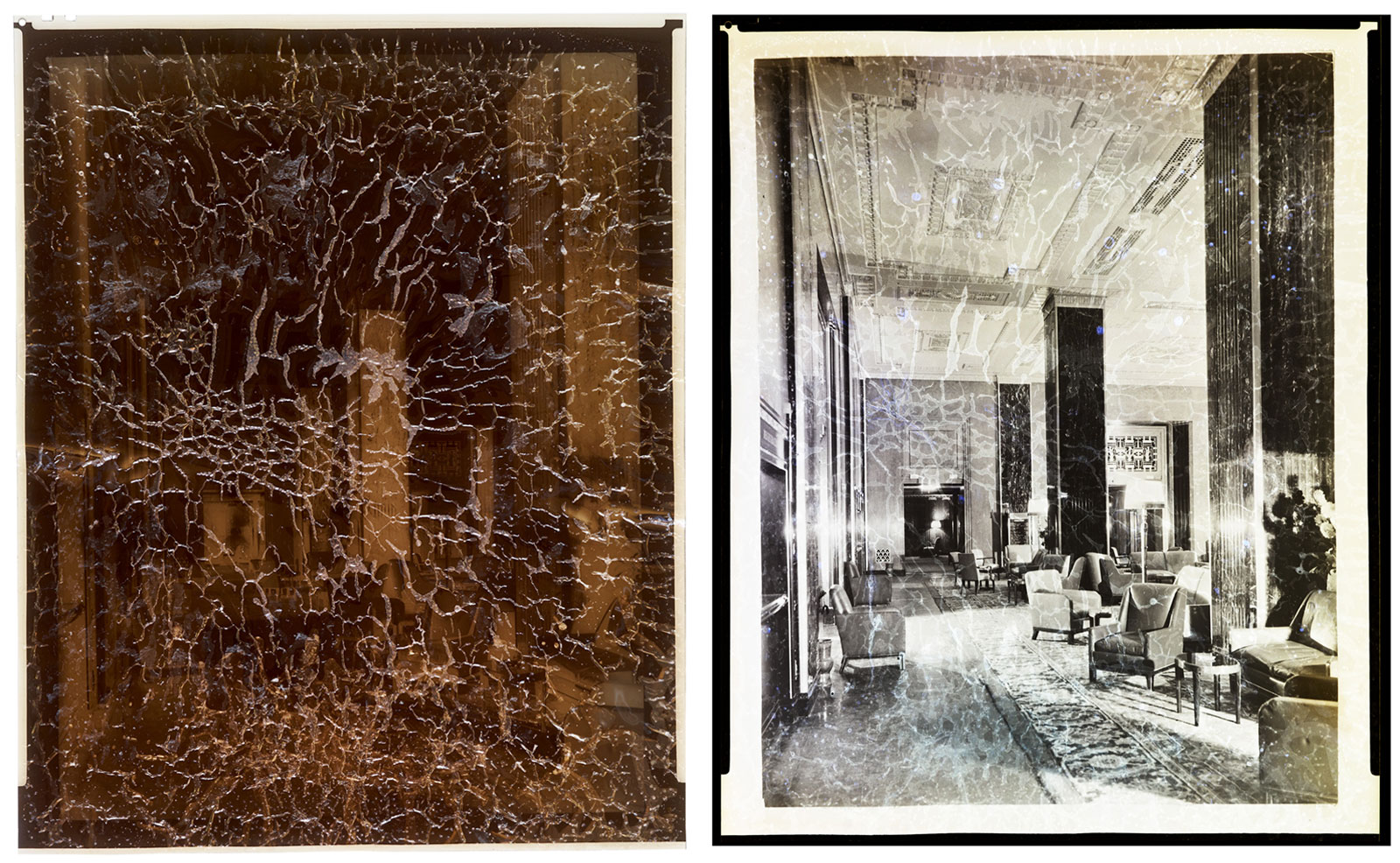

Within the Schultze & Weaver archive are 87 original 8x10-inch silver gelatin negatives on cellulose acetate film. When they arrived at the museum, the negatives—all of photographs taken by the firm in the 1940s and '50s—were badly stored in acidic cardboard boxes, and the film exhibited clear signs of damage. While we knew that the images were related to the firm's architectural projects, no prints accompanied them, and the negatives were too deteriorated to see their contents clearly.

Cellulose acetate film is an unstable material due to its chemical composition, which can cause an autocatalytic reaction known as vinegar syndrome. The name comes from the strong vinegar odor produced by the acetic acids that form during the deterioration process. This type of chemical degradation can occur in ordinary room conditions, and it produces film distortion, shrinkage, cracking, blistering, channeling, and in its final stages, separation of the emulsion. The consequences are irreparable losses of the photographic image and complete disfigurement of the actual object.

Unfortunately, the negatives presented advanced levels of vinegar syndrome, they were too fragile to handle, and the images were impossible to see. They were likely irremediably lost . . . or were they?

Preserving and Digitizing the Material

At the beginning of 2023 and with the help of a grant from Conserv, we developed a project to save the Schultze & Weaver negatives. The plan integrated both digitization and preventive measures to accomplish two goals: recover what is left of the images and slow down the negatives' rate of deterioration before they are destroyed.

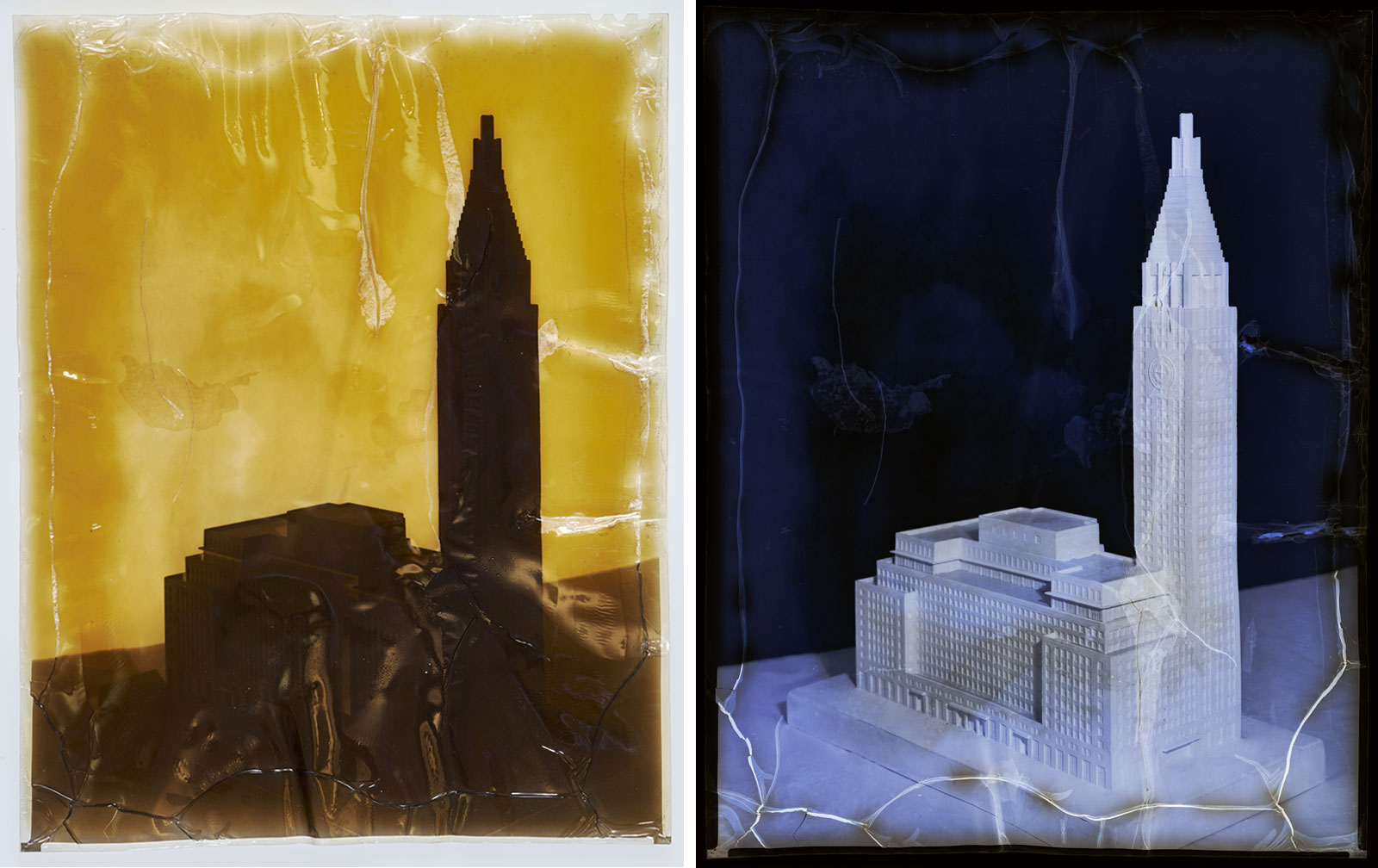

The project started with recovering the images through digitization. Each negative was cataloged, had its condition assessed, and then was carefully scanned. The scanning was completed with a Phase 1XF photographic camera and a light table, which captured the negatives at high resolution (up to 80MP). The scans were then rendered into "positives" using Photoshop, without any enhancements, to see what the photographs would have looked like originally.

Use the above slider, created using Knight Lab's Juxtapose tool, to compare the photographic negative to its digital positive. Aerial photograph, Park La Brea Housing Development, Los Angeles, California. Schultze & Weaver, architects. TD1994.446.30.

Even though the negatives were highly deteriorated and some of the damage is visible in the images, the process resulted in remarkably clear and detailed views of building facades, interiors, architectural models, renderings, and drawings. The new digital surrogates can now be enjoyed and studied on The Wolfsonian's online catalog without the need to handle these fragile objects.

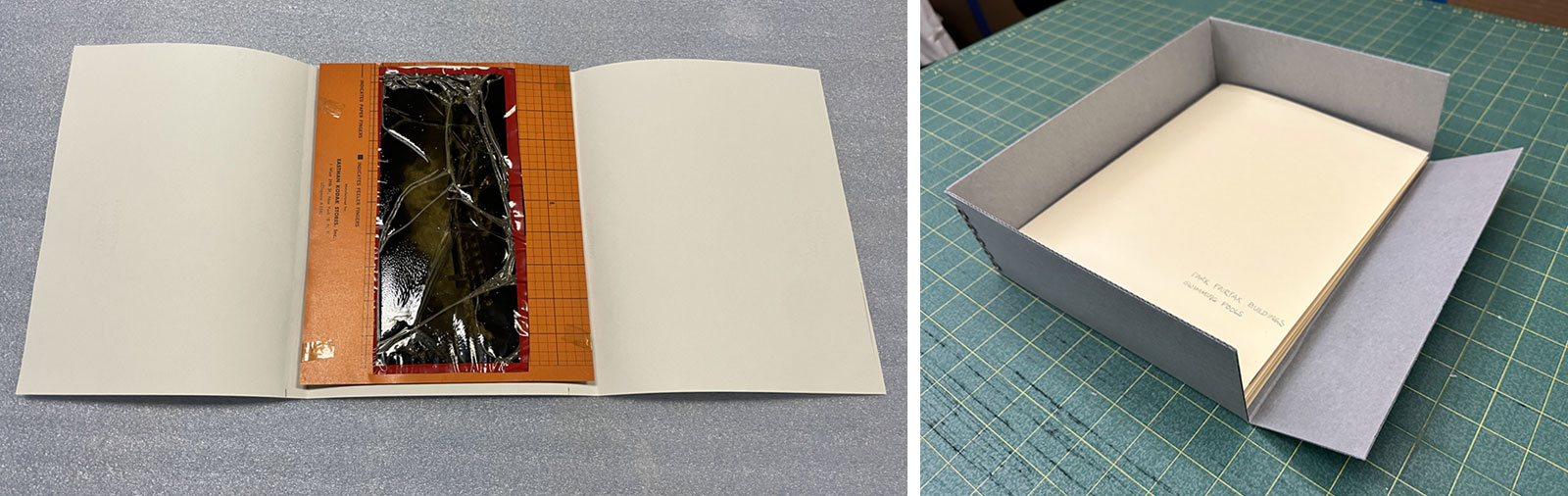

While the images were recovered, we still had the challenge of saving the actual negatives. Due to its high cost, conservation treatment of individual items was out of the question, but there were still other actions that we could take to preserve them.

According to the Image Permanence Institute, a leading research institution for the preservation of photographic materials, cellulose acetate negatives are better preserved in cold temperatures. Due to the autocatalytic nature of cellulose acetate degradation—which at room temperatures produces acetic acids that then react again with the film to produce more acetic acid—the best tactic for slowing down the chain reaction is freezing. If stored at levels below 30oF and at a low relative humidity, degraded cellulose acetate film's lifespan can be extended up to 110 years!

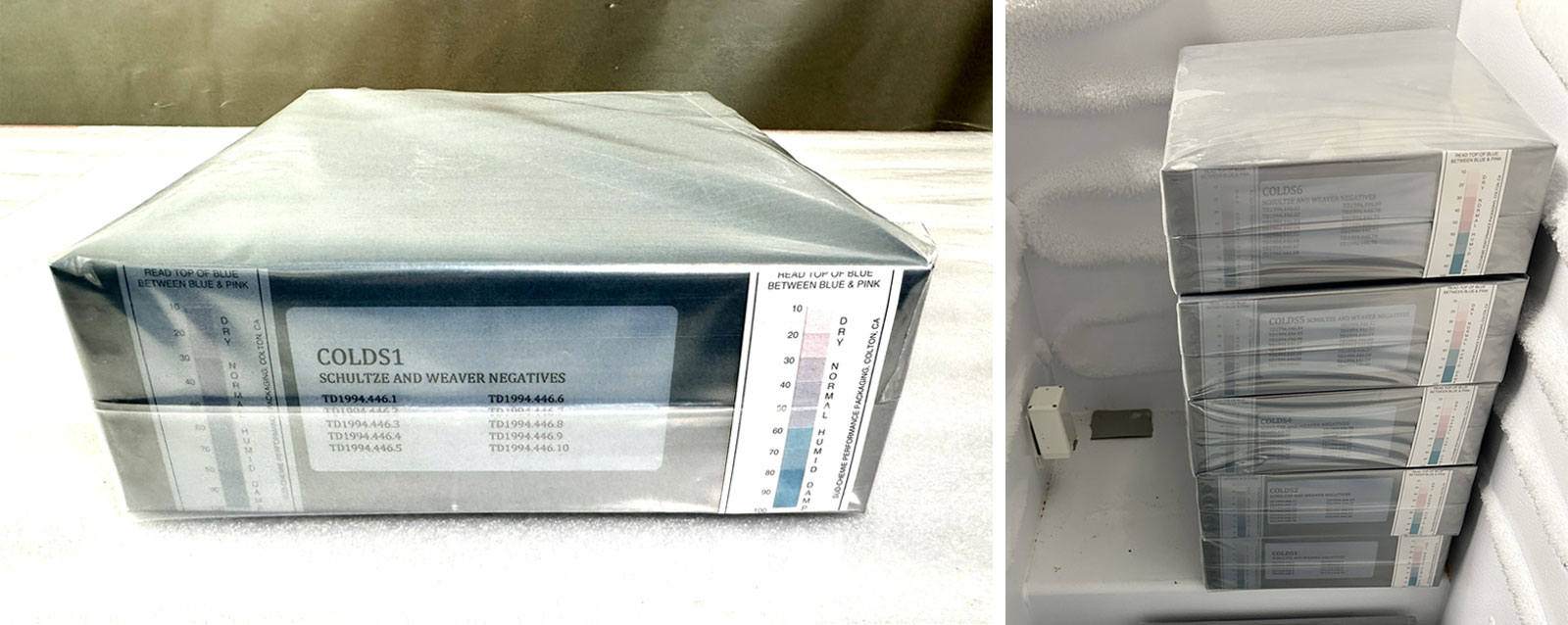

For that reason, the second phase of the project involved packing the negatives in a vapor-proof ensemble consisting of individual buffered cardstock folders inside acid-free boxes. A double layer of static shield and polyethylene bags protects each box from drastic changes in relative humidity, while small RH cards help us monitor the level in each package. Following recommendations from the National Park Service, the sealed boxes are now safely stored in a freezer that maintains a constant temperature of -40oF, effectively freezing the negatives for posterity.

This project showcases how preventive measures are effective methods for extending the life expectancy of important collection materials, while at the same time expanding access to their contents and our understanding of their significance—both important cornerstones of The Wolfsonian's collections care mission. We would like to say that in the case of the Schultze & Weaver negatives, mission accomplished.

A version of this article originally appeared on Conserv. To view more images of our Schultze & Weaver negatives and to request reproductions, visit digital.wolfsonian.org.