March 25, 2024

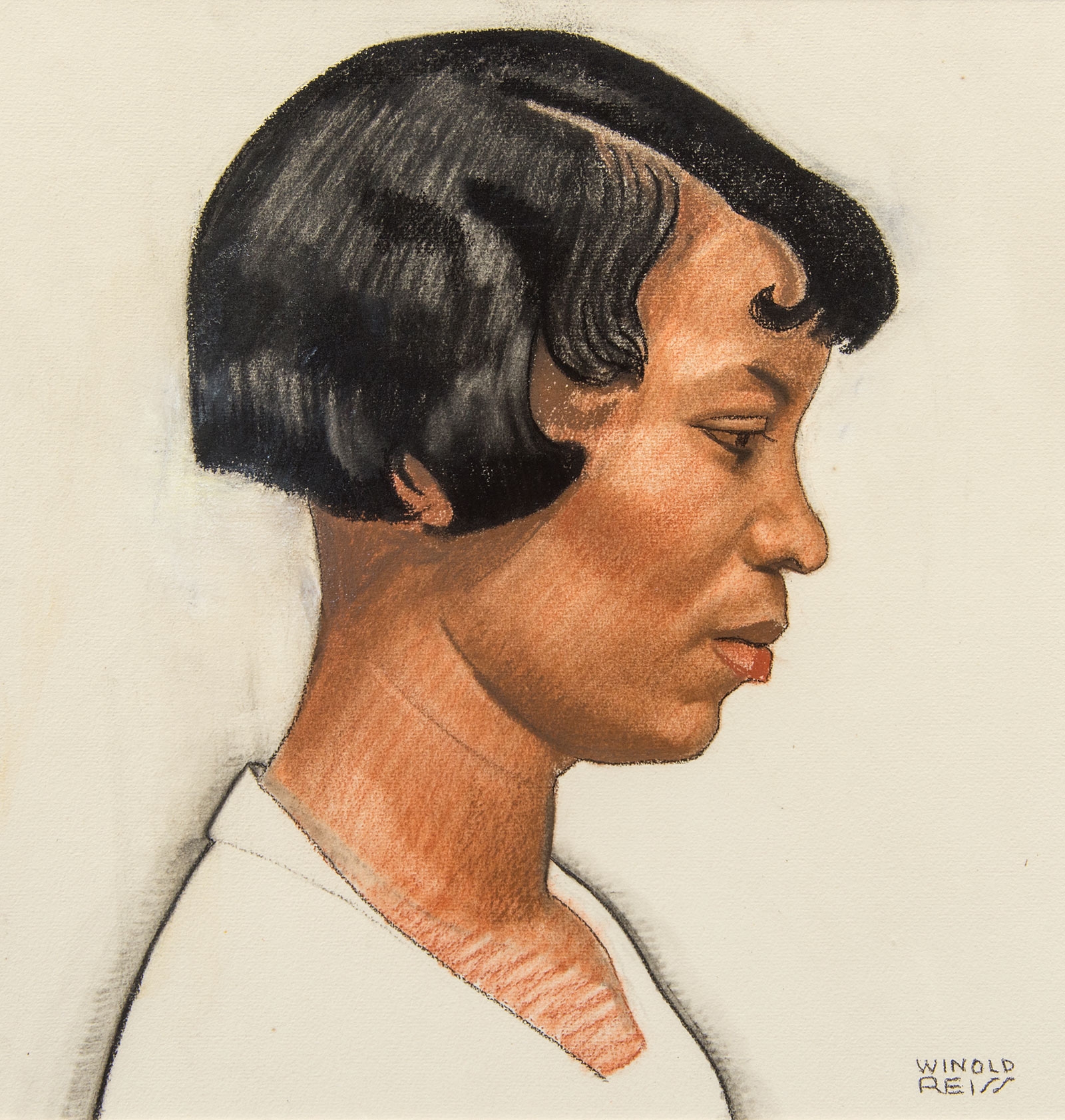

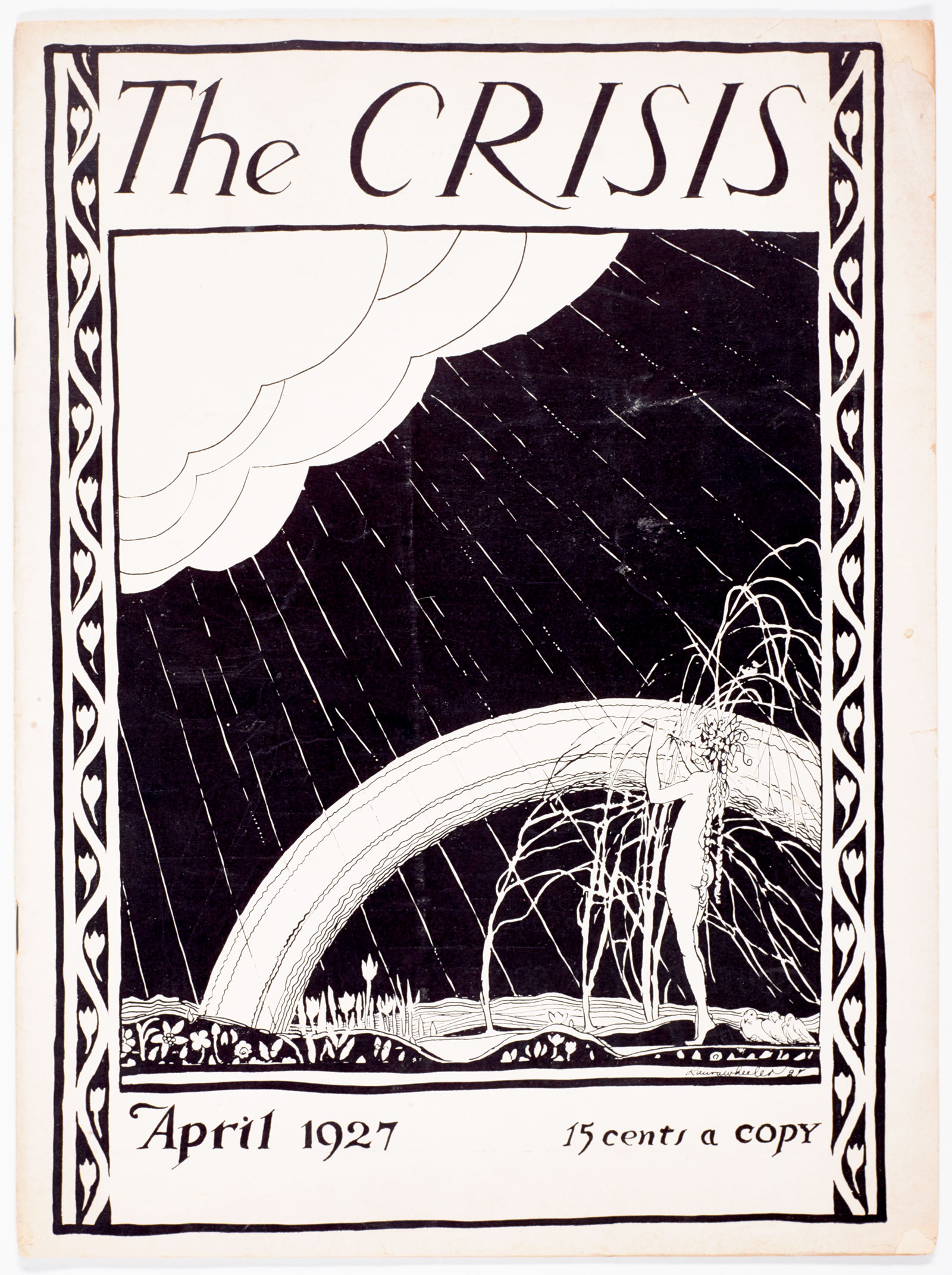

Our current exhibition Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance (November 17, 2023–June 23, 2024) highlights many female artists and writers who played key roles in shaping the movement. Yet despite their profound contributions, many of them remain overlooked today.

In recognition of Women's History Month, interpretation intern Karamot Adeola (FIU Class of 2025) delved into the lives of five remarkable figures—leaders in fields ranging from the performing, visual, and literary arts to business—who are either the authors or subjects of objects featured in the show. Read on for short biographies outlining the lives, careers, and legacies of Marian Anderson, Syvilla Fort, Zora Neale Hurston, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Sara Spencer Washington, and visit Silhouettes to spot historical works speaking to their cultural impact.

Interested in learning more? Mark your calendars for a talk by Dr. Jeffreen M. Hayes on June 7, 2024: There Is No Harlem Renaissance without Black Women.

– The Wolfsonian