October 25, 2023

By Silvia Barisione, Chief Curator

October 25, 2023

By Silvia Barisione, Chief Curator

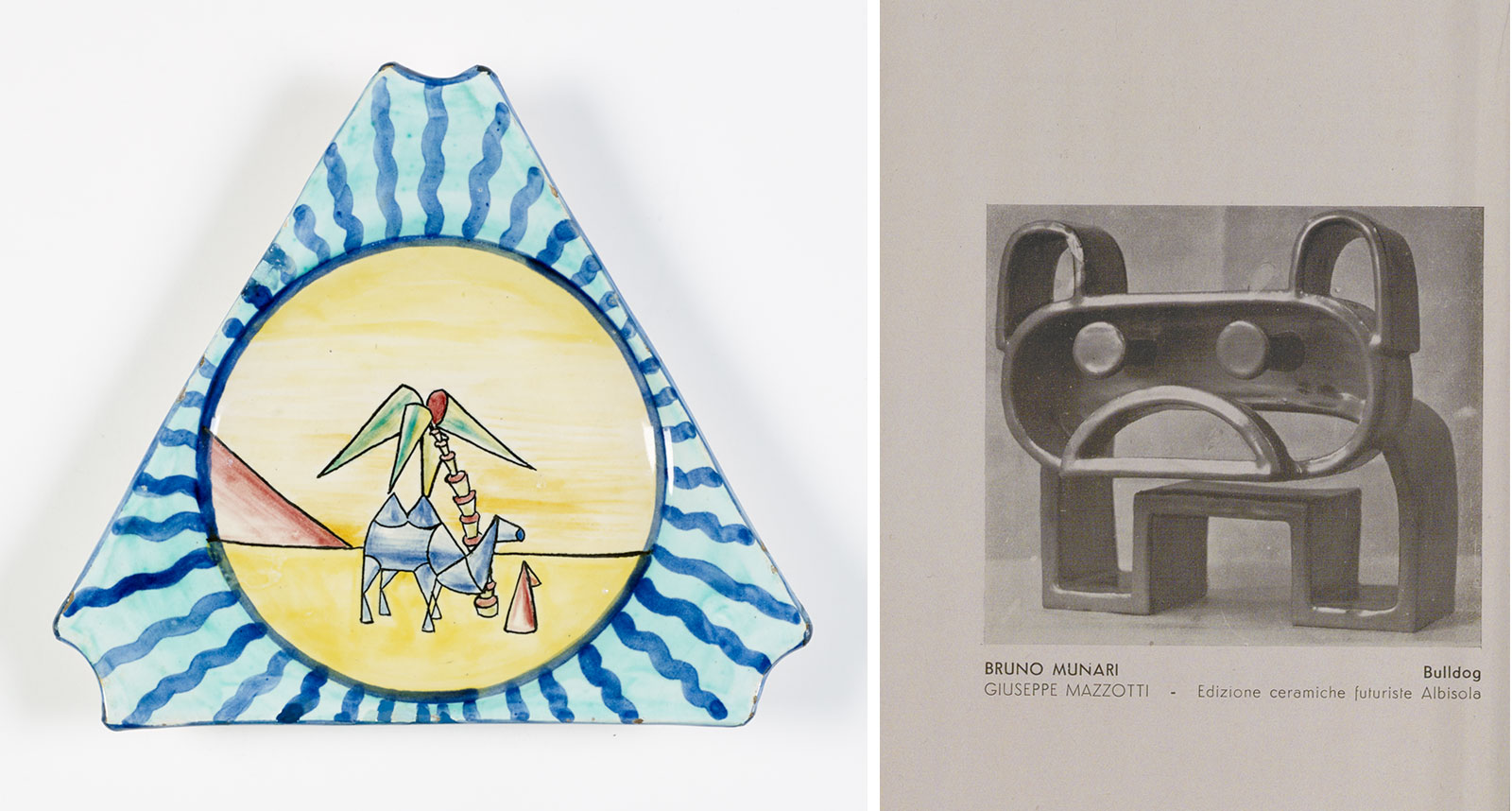

Antipasto service, 1929–30

Bruno Munari (Italian, 1907–1998), designer

Torido Mazzotti (Italian, 1895–1988) for Casa Giuseppe

Mazzotti, Albisola, Italy, maker

Glazed earthenware

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, 83.7.34 a–g

Among the unconvential landscapes in the newly opened Wolfsonian exhibition The Big World: Alternative Landscapes in the Modern Era, this glazed earthenware antipasto service by Milanese artist and designer Bruno Munari stands out as a significant example of Futurist representation of the natural environment on a functional object. Ceramic—celebrated in the Ceramic and Aeroceramic Futurist Manifesto[1]—became a favorite medium during the late 1920s into the '30s as Futurists pursued an overall involvement of the arts and architecture, an idea first expressed by artists Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero in their pivotal 1915 manifesto Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe:

"We Futurists . . . seek to realize this total fusion in order to reconstruct the universe by making it more joyful. . . . We will find abstract equivalents for all the forms and elements of the universe, and then we will combine them . . . to shape plastic complexes which we will set in motion."

They envisioned an artificial landscape as "an abstract landscape composed of cones, pyramids, polyhedra,"[2] which Munari illustrated in this piece created with ceramist Torido Mazzotti at the workshop of Casa Giuseppe Mazzotti[3] in Albisola. Two years earlier, his brother Tullio Mazzotti (renamed Tullio d'Albisola by Futurism founder Filippo T. Marinetti) had started the production of so-called "Futurist editions" at their father's factory, bringing the most important exponents of Marinetti's movement to the coastal town and making it the center of Futurist ceramic production in Italy.

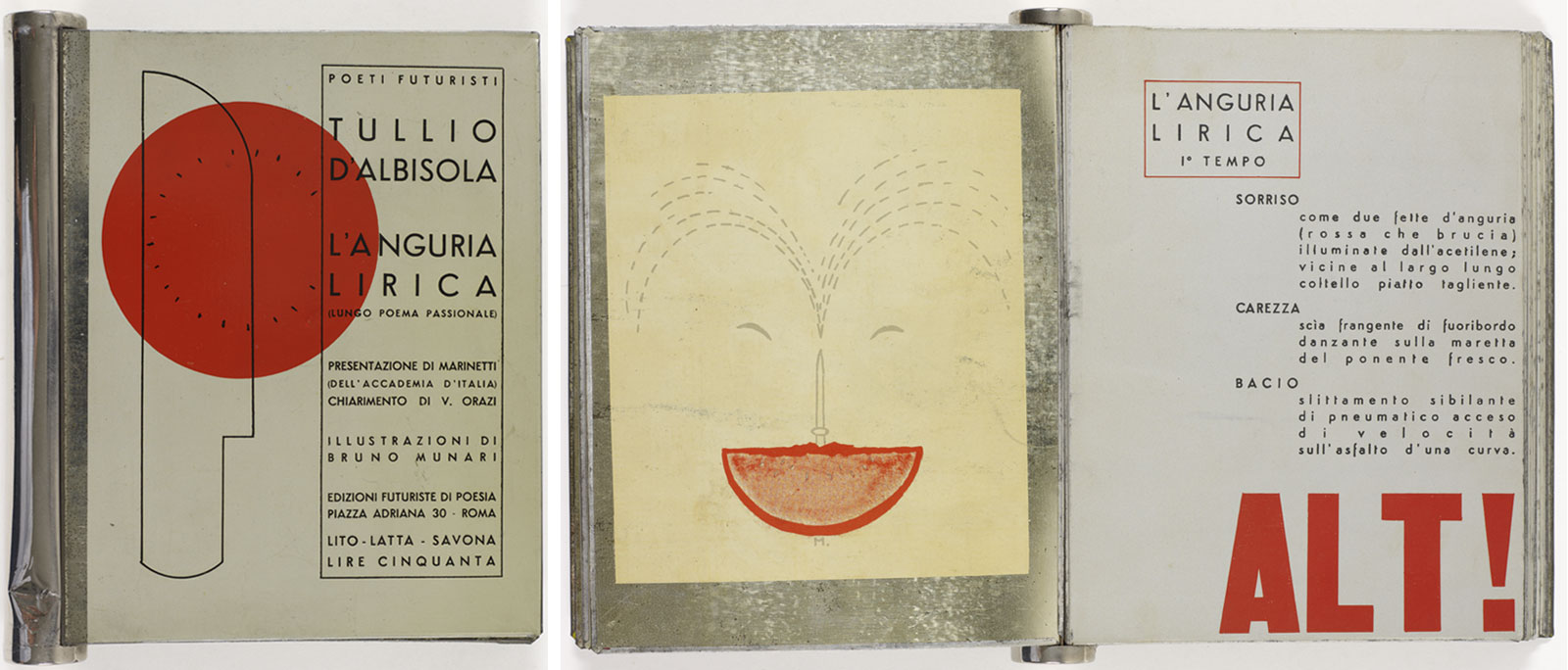

In his collaboration with Mazzotti, Munari—who had just joined the Milanese Futurist group—transposed his signature tube-like animals to ceramic, like with the famous Bulldog, whose forms seem to spring from the assembly of tubes, curved sheets, and bolts. A playful invention inspired by the machine aesthetic and nodding to the Futurists' excitement about industrial civilization, conical-formed figures first appeared in Munari drawings influenced by Depero and Kazimir Malevich. These animals populate the geometric landscape depicted on the entire surface of the antipasto service, which is composed of a saucepot surrounded by six small triangular plates. Munari's goal was the creation of a "completely new and original mechanical, animal, and vegetable world" that he asserted in the unpublished manifesto Dynamism and Muscular Painting [4], signed in 1928 with another young artist, Aligi Sassu (1912–2000).

The wide scope of the Futurist movement that informed Munari's early years certainly stimulated his multifaceted talent over a long career working across painting, ceramic, sculpture, illustration, graphic and product design, photomontage, film, and art theory. With Tullio d'Albisola he also experimented in bookmaking, illustrating Tullio's famous poem L'Anguria Lirica [The Lyrical Watermelon], printed on tin.

Endnotes

[1] The manifesto "Ceramica e aeroceramica – Manifesto futurista" was first signed by Filippo T. Marinetti and published in the Gazzetta del Popolo, a Turin newspaper, on 7 September 1938. It was then republished in Tullio d'Albisola, La ceramica futurista (Savona: Stamperia Officina d'Arte, 1939), signed by Marinetti with Tullio.

[2] Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero, Ricostruzione futurista dell'universo (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 11 March 1915). English translation, Caroline Tisdall (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1973).

[3] In 1903 Giuseppe Mazzotti founded the Casa Giuseppe Mazzotti in Albisola, where his sons Torido and Tullio worked with him. The latter officially began producing a Futurist line of work there in 1927, after meeting Marinetti in Milan, along with the Milanese artists Bruno Munari and Nino Strada.

[4] For more information on the unpublished manifesto Dinamismo e pittura muscolare, see Colizzi, A. (2011, April 19). Bruno Munari and the invention of modern graphic design in Italy, 1928 – 1945, 39.