July 19, 2023

By Angelica Lugo, Library Intern

July 19, 2023

By Angelica Lugo, Library Intern

Book, Jinrikisha Days in Japan, 1891Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore (American, 1856–1928), author

Harper & Brothers, New York City, publisherThe Wolfsonian–FIU, Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection, XC2012.08.1.361

Published in 1891, Jinrikisha Days in Japan swiftly brought its author Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore—an American travel writer, journalist, and photographer—recognition and credibility both in the U.S. and abroad. Scidmore embarked upon many voyages across the world throughout her life, later publishing works detailing her experiences. Among them, Jinrikisha Days in Japan (often shortened to Jinrikisha Days) was her magnum opus: compiling the events that transpired during her two visits to Japan, it reflects on a combined three years spent in the "land of the rising sun."

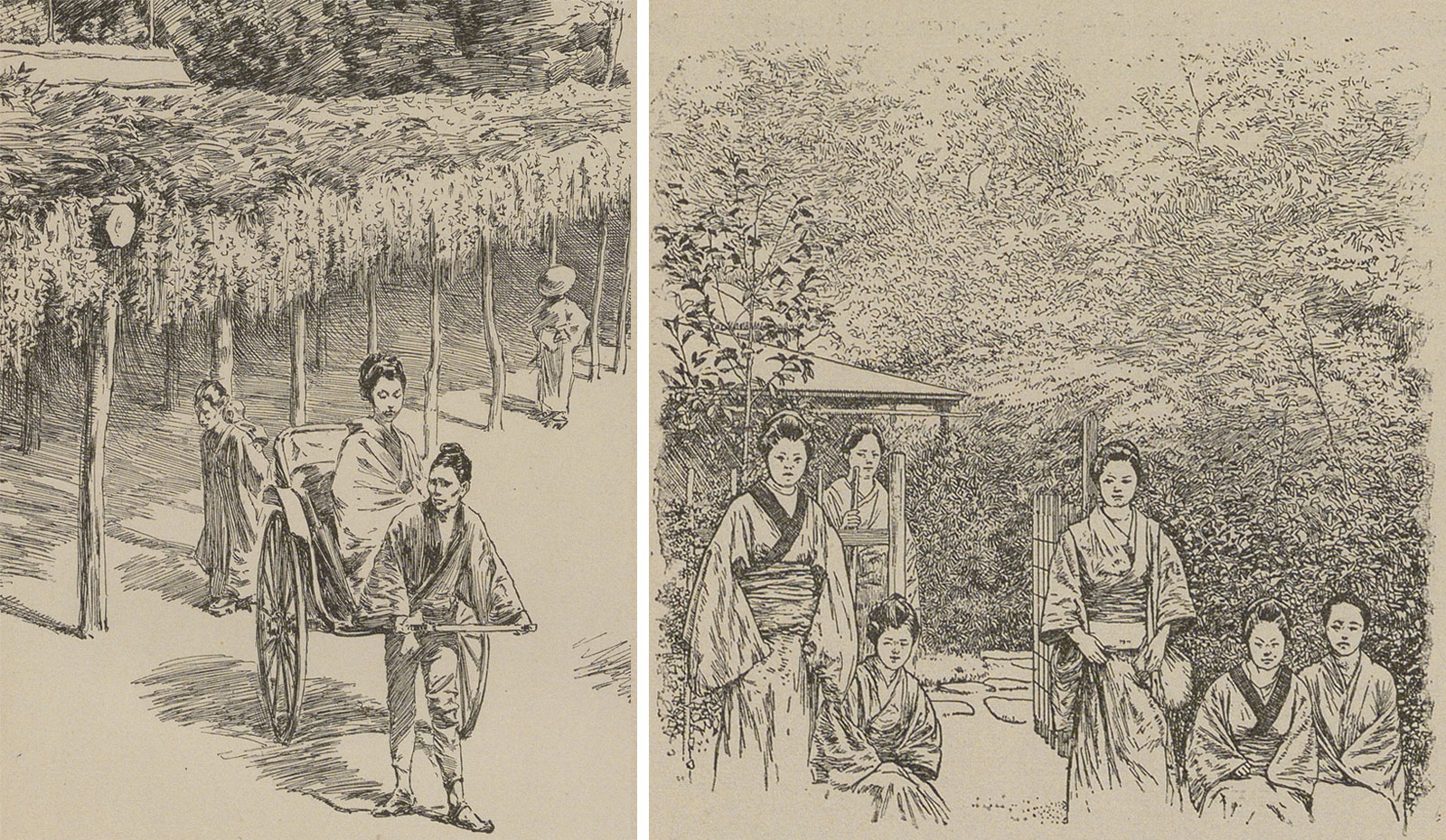

The book's title references the rickshaws (two-wheeled passenger carts pulled by another person) that Scidmore used to journey across Japan. Scidmore believed that Western scholars of her time neglected the country's quieter, "every-day" aspects, painting all of Japan to be like its most well-known cities, beyond which other writers rarely traveled. From the intricacies behind cultural practices to the atmosphere of the bay, she spared no details, transcribing the minutest of observations that would otherwise go unnoticed or become quickly forgotten. Photographs and illustrations, many by unidentified artists, bring her commentary to life on the page.

Though Scidmore's travelogue stands apart from those of her peers, Jinrikisha Days nonetheless reflects many of the biases typical of white Western tourists from the 1890s. While Scidmore was enchanted with the country, she saw it and the Japanese people as enigmatic and alien: "There is no end to the surprises of Japanese character, and the longer the foreigner lives among them the less does he understand the people, and the less do his facts contribute to any explanation." Scidmore's writing combines praise and condescending prejudice, such as when she notes the people's "childlike naivete," revealing how Jinrikisha Days was simultaneously revolutionary yet very much a product of its time.

Scidmore's esteem in Japan is perhaps surprising given the Orientalist themes of her work, but not in light of her role in creating ties of friendship between it and the U.S. In 1912, she brought 6,000 young trees—all Tokyo-donated Japanese cherry blossoms (sakura)—to Washington, D.C., with the support of First Lady Helen Herron Taft. After Scidmore died in 1928, her loved ones and the Japanese government worked together to lay her ashes to rest in Japan's Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery, despite her wishes for a simple funeral. Her gravesite is marked by a commemorative plaque maintained by Japanese supporters and is visited every year during cherry blossom season by a Japanese group, the Eliza Scidmore Cherry Blossom Society (Sakura-no-Kai). Their interest in Scidmore's career can be traced to the 1980s, when a Japanese translation of Jinrikisha Days came to Japan more than 50 years after her death.

In poetic testimony to Scidmore's legacy in both countries, clones of her Tokyo trees from the American capital were sent back to Japan; the U.S. has sakura from Japan, and Japan has sakura from the U.S.