April 14, 2023

By Gianella Cimadevilla, Library Intern

April 14, 2023

By Gianella Cimadevilla, Library Intern

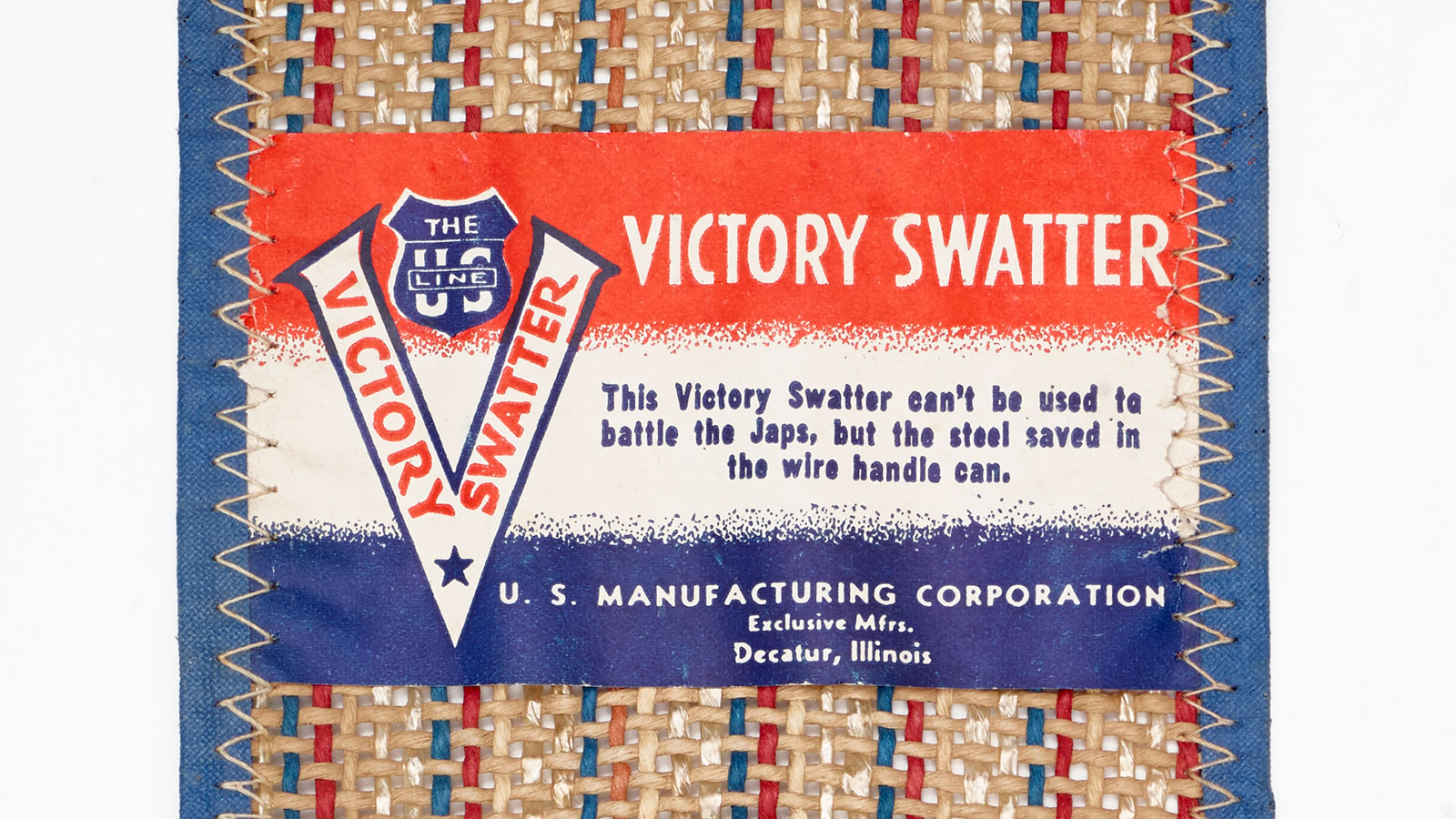

Fly swatter, Victory Swatter, 1942–45

U.S. Manufacturing Corporation, Decatur, Illinois, manufacturer

Wood, plastic, cloth, thread

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, XB1994.177

After the United States officially entered the Second World War in December 1941, domestic military production quickly went into overdrive. Shortages of tin, steel, and iron impacted the country throughout the early 1940s, leading to stringent federal rules restricting the use of these metals in commercial and civilian products such as canned goods and everyday household appliances.

In compliance with government regulations, the U.S. Manufacturing Corporation designed the non-metal Victory Swatter, proudly boasting on the front flap: "This Victory Swatter can't be used to battle the Japs, but the steel saved in the wire handle can." Metal-free items like the swatter allowed the government to conserve vital resources for manufacturing aircrafts, weapons, tanks, and trucks critical to the Allied forces' war effort. Echoing this nationalistic bent is the swatter's color scheme—red, white, and blue—a striking expression of patriotism and a visual call to victory.

The Victory Swatter features a couple of other key differences from its earlier iterations. Robert R. Montgomery filed the original patent for the fly swatter in 1899, dubbing it the "fly killer." Conceived as an alternative to the common solution of a rolled-up newspaper, the open wire netting of the fly killer would produce a "whip-like swing," killing flies swiftly and efficiently. In comparison to Montgomery's patent, the Victory Swatter is instead designed with a closed cloth netting, resulting in more air drag, a weaker swing, and ultimately a less effective (and less deadly) weapon than the original "killer."

The Victory Swatter serves as a time capsule of the economic, political, and social climate of the U.S. during the war. While many contemporaneous American propaganda pieces in the Wolfsonian collection direct satire and public anger against all three of the Axis powers, this artifact specifically targets the Japanese, the perpetrators (i.e. the "flies") behind the December 7, 1941, surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. This anti-Japanese sentiment—often going so far as a racially charged call for revenge—permeated American public discourse during the war, finding its way into even the most ordinary and mundane of objects.