September 23, 2022

By Victoria Calveira, Library Intern

What is it about exhibitions that make them so enticing? How do curators shape a polished and cohesive narrative? Although much effort goes into creating storyboards, selecting items, and writing descriptive and interpretative text, in the end it is all about imparting the audience with a central message.

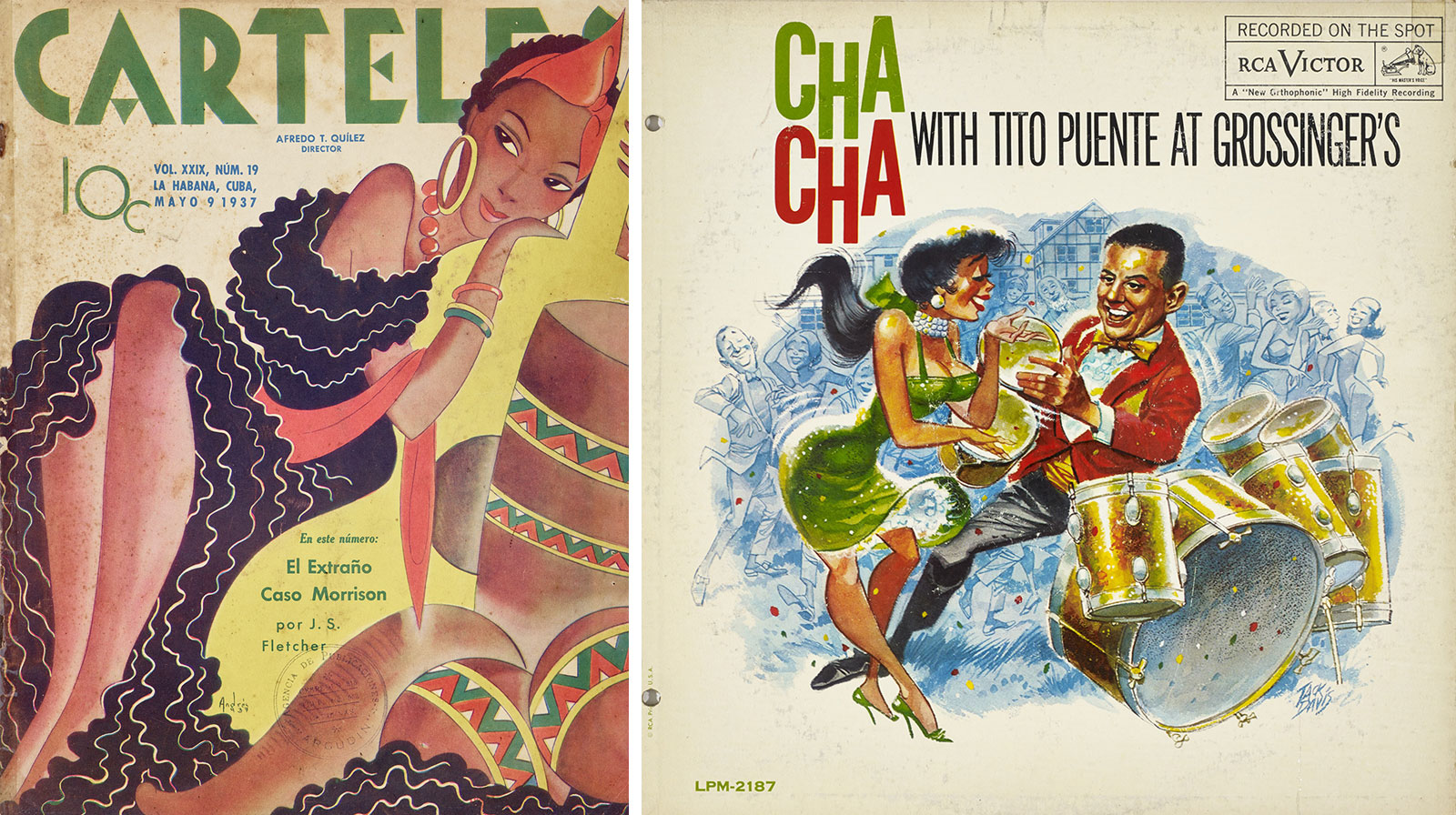

I have spent much of my summer semester internship working with chief librarian Frank Luca as he organized Turn the Beat Around, an upcoming Wolfsonian exhibition examining the Afro-Cuban origins of popular music and dance. A central component of the installation is how the artwork—mostly selections from the collection, dating from the 1930s to the '60s—expresses this theme, acting like a litmus test for ever-changing culture. The show traces influential styles from rumba and conga, to Afro-Cuban jazz, to mambo, cha-cha-cha, and salsa, revealing how Cuban and American culture intermixed.

Before this project, my involvement in museum installations was limited to the end stages, after the objects were selected and storytelling was complete. Leading tours has required me to have complete command of an exhibition; I boosted my knowledge by reading labels, listening to curator talks, and applying the art historical training of my coursework to prepare myself to speak publicly about a show's art and central themes. But I was not aware of how much work goes into making exhibitions a reality.

Over the course of my time with The Wolfsonian, I found myself questioning my assumption that curators had full reign and say over what they curated, as if exhibitions were a lone pursuit. If I were to pinpoint my most surprising experience, it would be when Dr. Luca invited me to stay for a meeting with the exhibition designer and exhibition manager. From the perspective of the proverbial fly on the wall, I saw how aspects of an exhibition are coordinated, negotiated, and carefully thought through between different teams. The conversation that unfolded before me included a back and forth between what was best for the exhibition conceptually and logistically. I remember lots of "no, this can't go here," followed by "we only have X amount of X," and "the space is only this big." I hadn't considered before how multiple departments must interact and make decisions together to bring an exhibition to life.

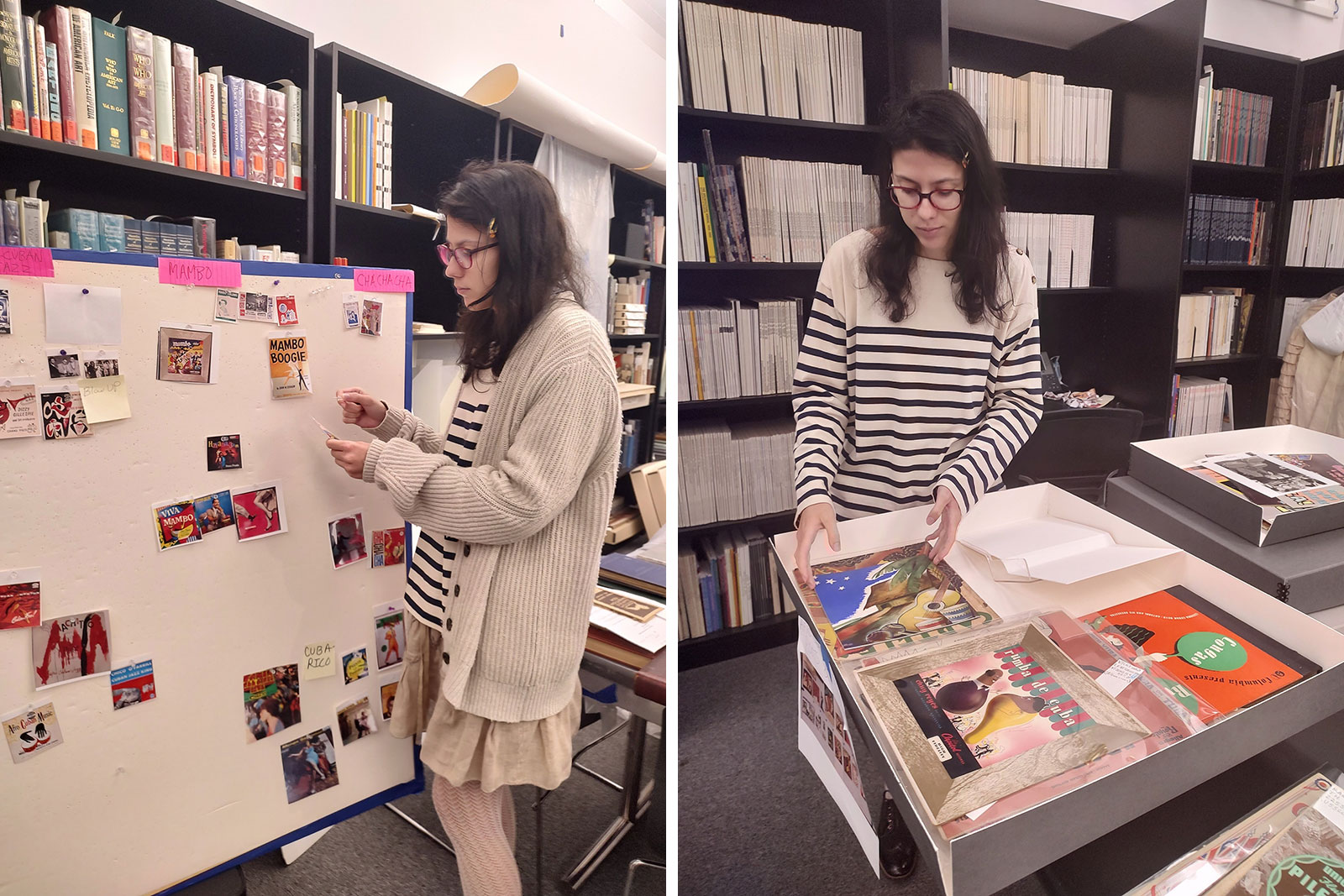

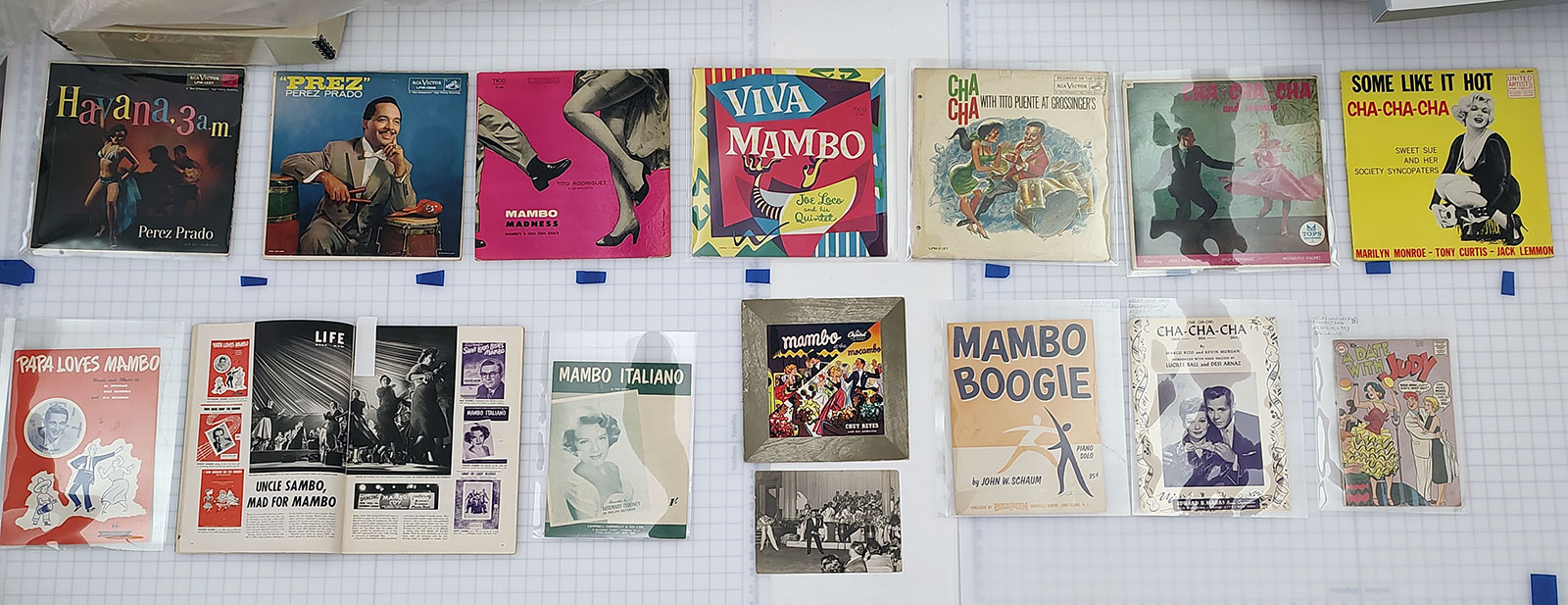

I discovered that organization is key to the curatorial process. At The Wolfsonian, exhibition development is visualized on analog, old-fashioned foam-core storyboards. Images of each item proposed for inclusion are tacked onto the storyboards beneath the various defined sections of the show, with some being added, substituted, or dropped as the installation evolves—necessitating a lot of printing, cutting, and pinning. I doubt that the average museum visitor, when walking through an exhibition, imagines the many times the printer didn't cooperate, the frantic trips made to find more pins, and how often we had to reconcile what remained on the boards with what the curator needs to illustrate their message. The final installation can be, and most often is, a very different product from the first idea and the various incarnations on the storyboards.

While many who are unfamiliar with the curatorial process are charmed by the storyboards, I found another tool—the Excel checklist—to be the most technical, and interesting, method of organization. All contents of a show are sifted through, researched, vetted, and sometimes cut or replaced in a sheet divided into thematic categories. Assisting Dr. Luca, I spent a great deal of time in the minutiae of this document, adding to individual object descriptions or providing titles, dates, and publication information. This exercise gave me a strong sense of the full scope of the show as well as an idea about how each object speaks to the larger story in its own distinct way. Any time I asked, Dr. Luca would share the unique backstory of an item and explain how it connects to the overall themes of the installation.

Another aspect of planning is prepping the objects for display. This stage is exciting, as is any anticipated stage nearing the finish line. I contributed in two ways: helping to strategize object layouts and preparing Mylar backings for when the pieces rest in the cases. The process of determining layout was a totally dynamic one; objects shifted around until all the puzzle pieces fit. Dr. Luca would think aloud to let me in on the process, noting how the visual weight of different object sizes and shapes had to be balanced, and how colors should work harmoniously across the case. Every so often he would ask me, as a fresh set of eyes, how the compositions worked. I also focused intermittently on constructing Mylar backings, thin sheets of inert polyester film that protect the objects. They may look neat in the case, but their assembly is not so neat—especially with the looming knowledge that they would be displayed to thousands of visitors, my hands fumbled quite a few. Nonetheless, these crucial steps were a project highlight for me.

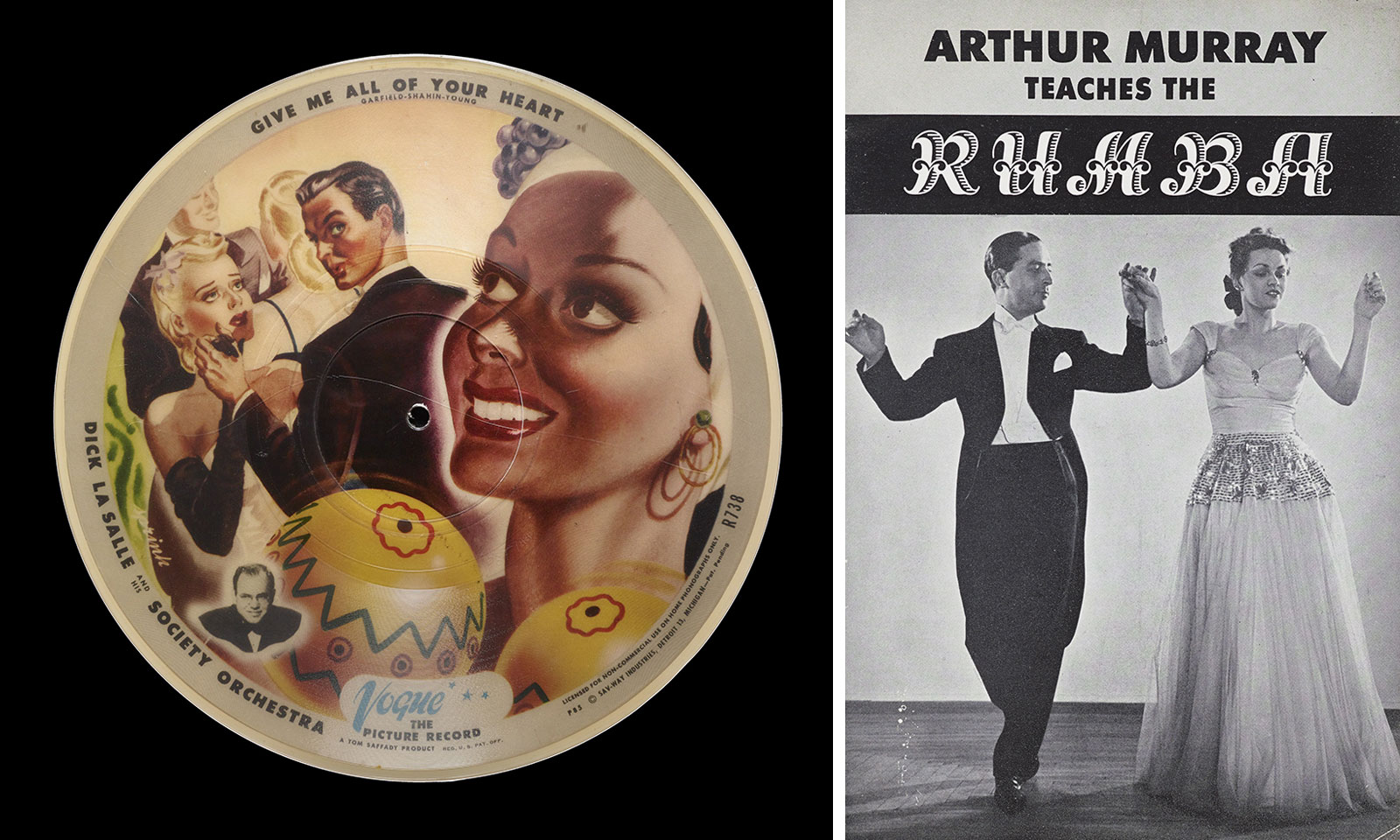

After so much exposure, the items in Turn the Beat Around have left their imprint on me. I find it very interesting how objects can magnetically relate to one another, or to a larger concept; one of my favorite pieces, and also Dr. Luca's, is a picture record. The dance instruction sound recording includes an image of an American couple on the dance floor, with the male partner obviously distracted by an Afro-Cuban woman shaking maracas. The image is so evocative and full of undertones that show the seductive power of Afro-Cuban music to an American audience. An Arthur Murray pamphlet is an additional favorite, as it so clearly shows just how much Cuban music and culture, like the rumba, were adapted to conform to the typically American ballroom dance scene.

Watching the journey from concept to exhibition was an exciting experience, one that showed me the flurry of objects, ideas, and effort that swirl behind the scenes at a museum. What I liked most about curation was sharing perspective—that of the objects, the curator, and even the visitor. I was able to glimpse a prized moment when local bandleader Tito Puente, Jr., came to the library to get a sneak peek at the show. Son of the legendary Puerto Rican musician Tito Puente, Tito Puente, Jr. loaned a few pieces for the exhibition that speak to his father's legacy; his reactions to different objects from the Wolfsonian collection made clear that Cuban music is in his lifeblood. I loved witnessing the exchange of stories: Dr. Luca's historical explanations, and Puente's personal anecdotes about what these artifacts of Cuban culture mean to him personally.

I am so excited for when Turn the Beat Around opens to the public and can inspire awe and appreciation in people of all ages and backgrounds. It will be a special experience showing my family and friends an exhibition that I played a part in shaping.