August 25, 2022

By Shoshana Resnikoff, Curator

August 25, 2022

By Shoshana Resnikoff, Curator

Desk and chair, c. 1935

Maurice Adams (British, 1887–1941), designer

Maurice Adams, Ltd., Gloucester, England, maker

Australian walnut, upholstery

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Promised Gift, WC2007.2.14.3.1–.2

In 2018, The Wolfsonian opened Deco: Luxury to Mass Market, an exploration of the museum's rich holdings of European and American Art Deco material. In working on the exhibition, the curators (Silvia Barisione, myself, and Whitney Richardson) realized something surprising: we have far more Art Deco objects from the United Kingdom than we knew.

England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are not known as centers of Art Deco production. Design history often focuses on the late 19th and early 20th centuries as high points in British design, when thinkers such as John Ruskin and designers like William Morris championed an approach to art and life that would become the Arts and Crafts Movement. Focusing on historic craftsmanship techniques and aesthetics drawn from nature and history, many adherents of the Arts and Crafts Movement brought a political lens to their work—Morris, for instance, was a dedicated socialist and critic of industrial factory production. To be an artist or designer working in this style was, on some level, to be engaged with a capital-M "Movement," or at least adjacent to it.

What came out of Great Britain decades later, during the interwar period, is another creature entirely—works made by a diffuse group of designers figuring out independently how a modern world should look and feel, and (importantly) what qualities their clients wanted their "modern world" to reflect. No object better represents that shift than Maurice Adams's desk and chair, produced circa 1935.

Adams first rose to prominence as a maker of neo-Georgian furniture that reinterpreted historical styles for contemporary audiences. In the 1930s, however, he became interested in abstracted, geometric designs, as seen in the curved edge and blocky body of this desk. He was likely drawn to this style through a combination of personal evolution and market savviness, as his urbane clients were exposed to the more machined designs coming out of Art Deco workshops throughout Europe. Yet despite the clear modernist inspiration for his furniture, Adams relied largely on hand-tooled production in a large workshop staffed by skilled workers, an Arts and Crafts model that itself references more historic and idealized periods of production. In this combination, the desk captures a very English tension between the past and the future.

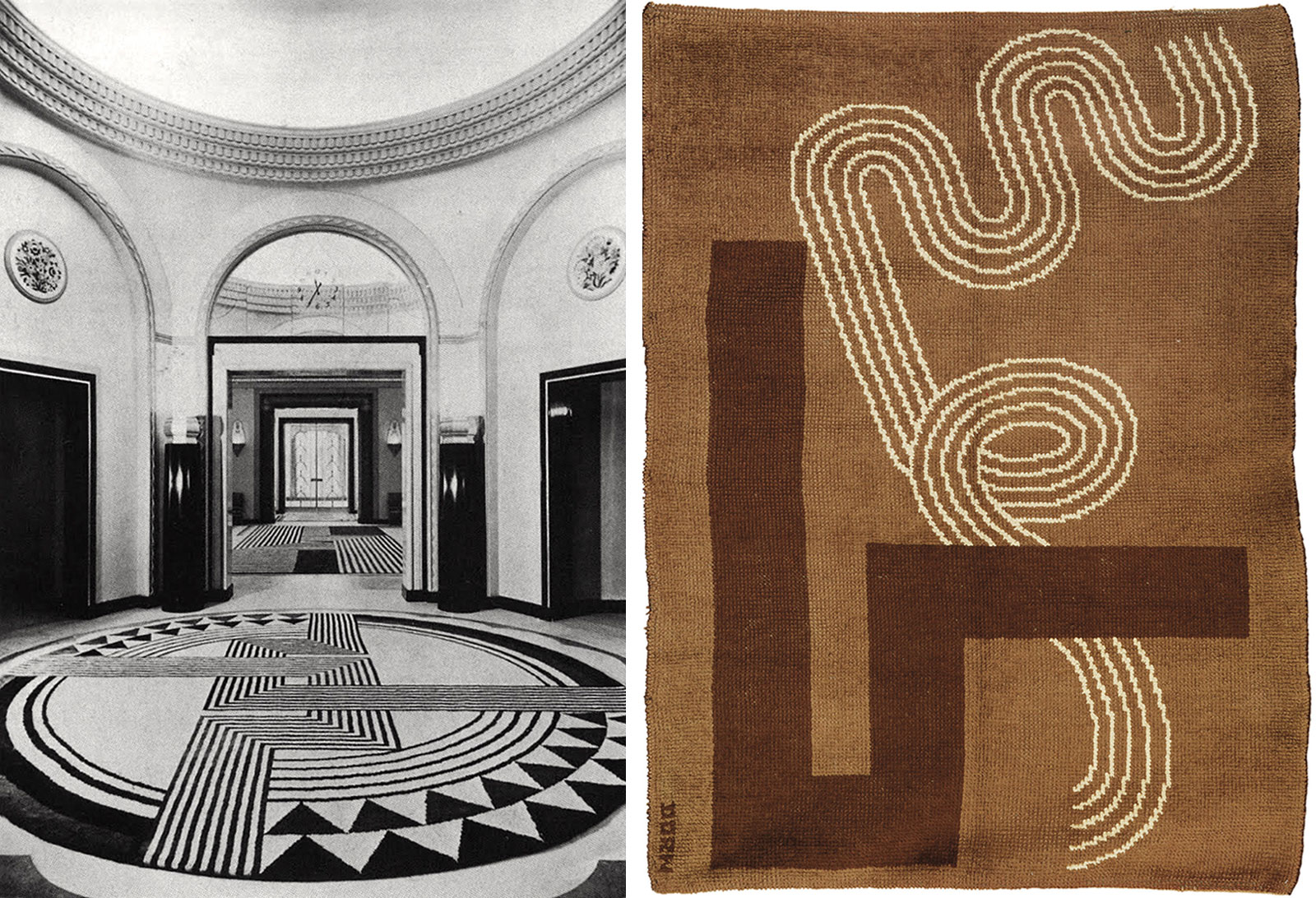

Adams's desk has one more intriguing element: the chair upholstery. Perfectly sized to slide into the knee hole, the chair completes the desk's smooth façade when tucked—a puzzle piece that has found its spot. When pulled out, however, it reveals burgundy upholstery with a jazzy, curvilinear pattern that matches the tempo of 1930s London life. In conversation with Wolfsonian chief curator Silvia Barisione, design expert Simon Andrews theorized that the upholstery might have been designed by Marion Dorn, a leading American-born British textile designer working in London at the time. Known for her dynamic designs for London Transport vehicles as well as her sculpted carpets commissioned by hotels and major homes across the city, Dorn's work in the period was marked by its simplified color palette, overlapping geometric patterns, and interlocking swirling lines. Silvia connected with Dorn scholars in the UK to share her theory, but while they agreed it was likely correct, no one could confirm it.

It is possible that by undoing the upholstery, we can learn more about its maker; textiles often feature manufacturer information on the selvedge (at the edge of the fabric), which would give us next steps for research. One potential avenue—suggested by the Victoria & Albert Museum's furniture curator, Victoria Bradley—is looking into John Holdsworth & Co Ltd, manufacturer of Dorn-designed upholstery for the London Tube. We also hope that interest in Dorn, renewed by the recent Cooper Hewitt exhibition of her husband and collaborator E. McKnight Kauffer, will bring under-documented Dorn designs to light, revealing new leads. Until that point, however, the maker of our chair upholstery will remain a mystery—the kind that keeps museum workers researching and dreaming of possible answers.