March 11, 2022

By Lea Nickless, Curator

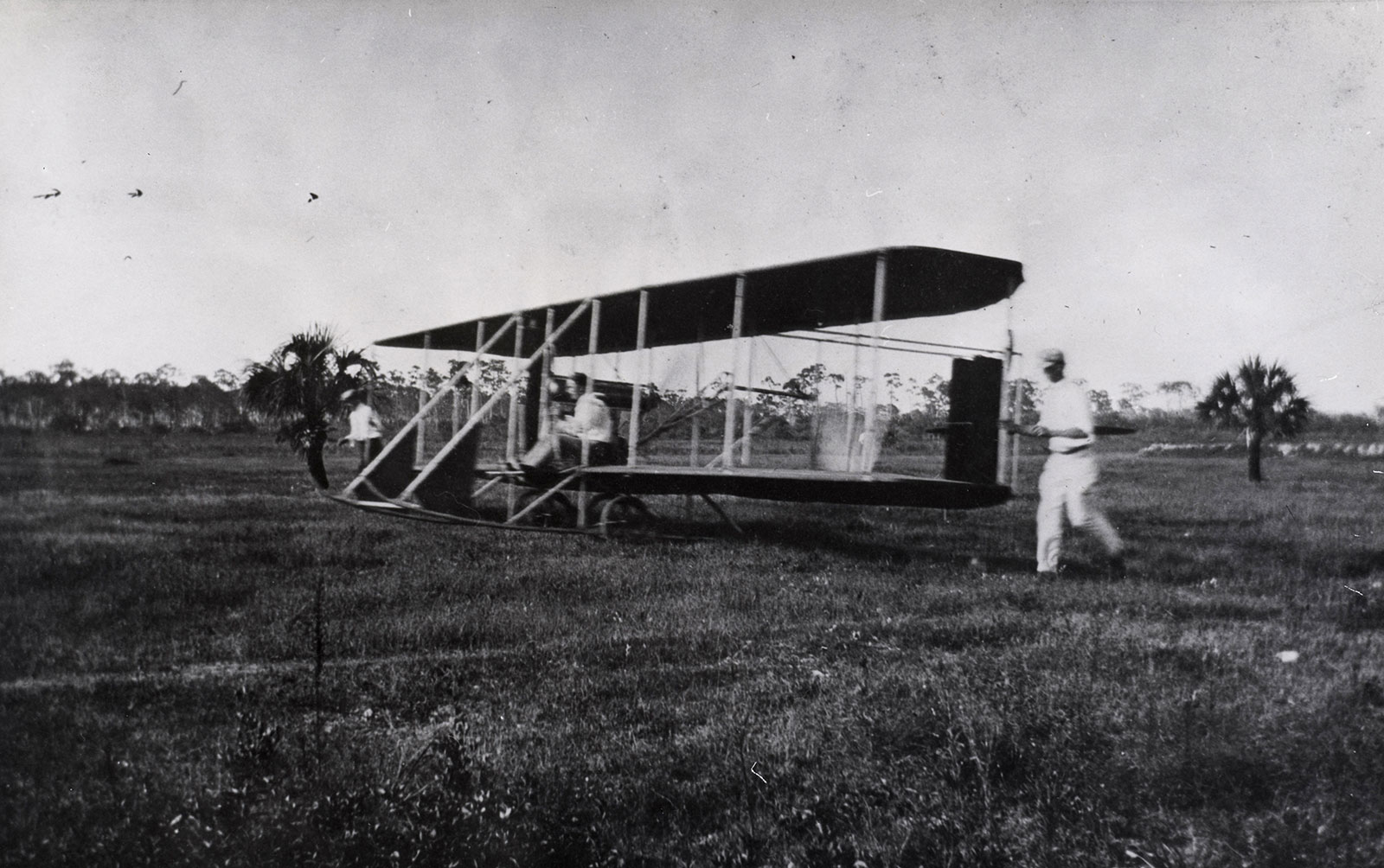

Miami was a young city, having just marked 15 years since its incorporation, when in July 1911 it witnessed its first airplane overhead. A crowd of 5,000—practically the entire population of South Florida at the time—gathered for an aerial spectacle as aviator Howard Gill piloted a Wright biplane over the Miami Golf Links, Miami's only golf club, now the site of Jackson Memorial Hospital. In the months leading up to the 3-day celebration, the city had been overcome with such excitement that The Miami Metropolis quipped, "a strange new malady has struck the Magic City . . . aeroplanitis."[1]

E. G. Sewell, president of Miami's Merchants Association and a future mayor of Miami, spearheaded the event, convincing local businessmen to finance bringing the airplane and flyer to town. Businesses closed to allow their employees to participate in the festivities that included military drills and dress parades, speed boat and motorcycle races, baseball games and firework displays. After his official aerial exhibition for the crowds, Gill took Sewell for a spin, making him the first airborne Miamian. Sewell was quoted in The Miami Herald, "it was the finest ride I ever experienced; the breeze was fine; the scenery the greatest ever. The Everglades, the drainage canal, the city of Miami, Atlantic Ocean and big steamers passing all being in plain view."[2]

Enamored by the experience, Sewell became an avid aviation booster, fervently promoting anything relating to flight. Within months, Sewell was corresponding with aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss to bring a pilot training school to Miami. In January 1912, the first Curtiss hydroplane arrived, docked on Biscayne Bay near the Royal Palm Hotel, and the Curtiss Aviation School launched. Airplanes quickly became a common sight, with seaplanes regularly landing on the bay and airfields popping up in Coral Gables, Hialeah, and on the Venetian Causeway. There was even a short-lived airfield and aviation school on Miami Beach east of Alton Road from 8th Street to around 10th Street—in 1916, Carl Fisher and Glenn Curtiss partnered on a site to train pilots for the First World War. Soon needing more land, Curtiss centralized his operations in Miami the following year.

By 1929, Miami was considered the most air-minded city in the country. On January 9, 1929, 10,000 Miamians, as well as aviation celebrities including Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart, gathered for the dedication of Pan American Field—now Miami International Airport. Postmaster General Harry S. New proclaimed that Pan American Field was destined to become one of the world's greatest airports; indeed, the new terminal was soon the busiest aerial port of entry in the United States.

To coincide with the dedication of the new airport, Sewell, now in his second mayoral term, inaugurated the first All-American Air Race in January 1929. Later known as the All-American Air Maneuvers, the 3-day aviation event continued for 28 years, attracted national as well as international flyers, and bolstered Miami's status as an important center for aviation. Well-attended from the beginning, these air meets took place at the Miami Municipal Airport in Hialeah and featured air races, flying exhibitions, and access to the latest in aircraft technology. Local support was enthusiastically encouraged—a 1931 newspaper ad for Belcher Oil urged, "Attend Miami All-American Air Races . . . the most sensational and thrilling events ever offered. You can help make Miami the World's Air Center."[3]

A concerted public relations and marketing campaign followed. In 1938, The Miami Daily News ran a competition to find a suitable slogan for the event. The winning entry, "The Olympics of Aviation," garnered 22-year-old Myrtle Moon of Homestead an all-expenses paid trip to Cuba, by air. There was even an annual competition for the title of "Miss Miami Aviation," its 1939 winner University of Miami student Ruth Shelley, who went on to represent Miami as part of the Florida Air Tour to the 1939 New York World's Fair. Upon her return, Shelley, who had become smitten with flying, took lessons and became a pilot. The media celebrated her as "the only aerial [beauty] queen in America who actually holds a pilot's license."[4]

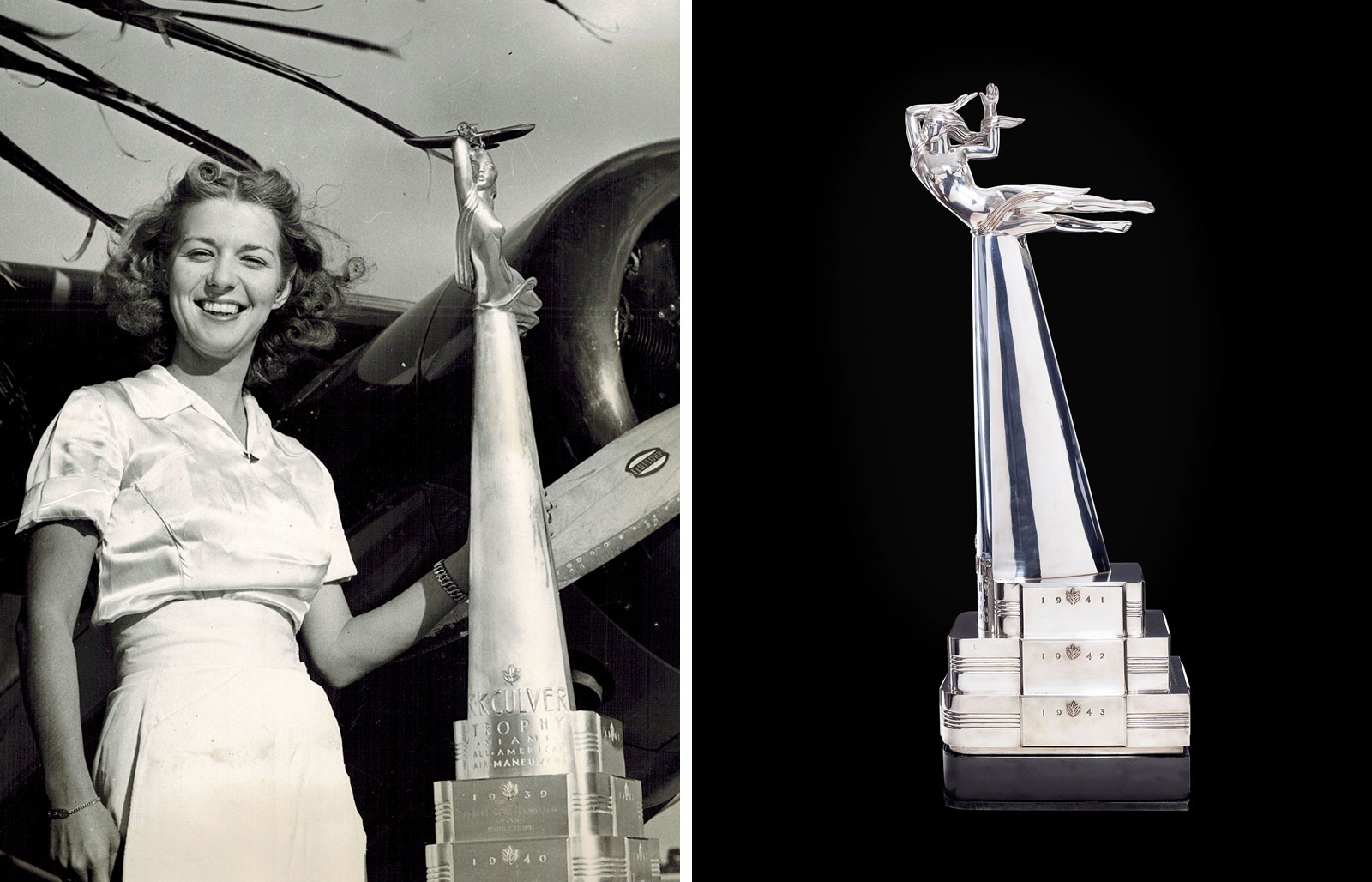

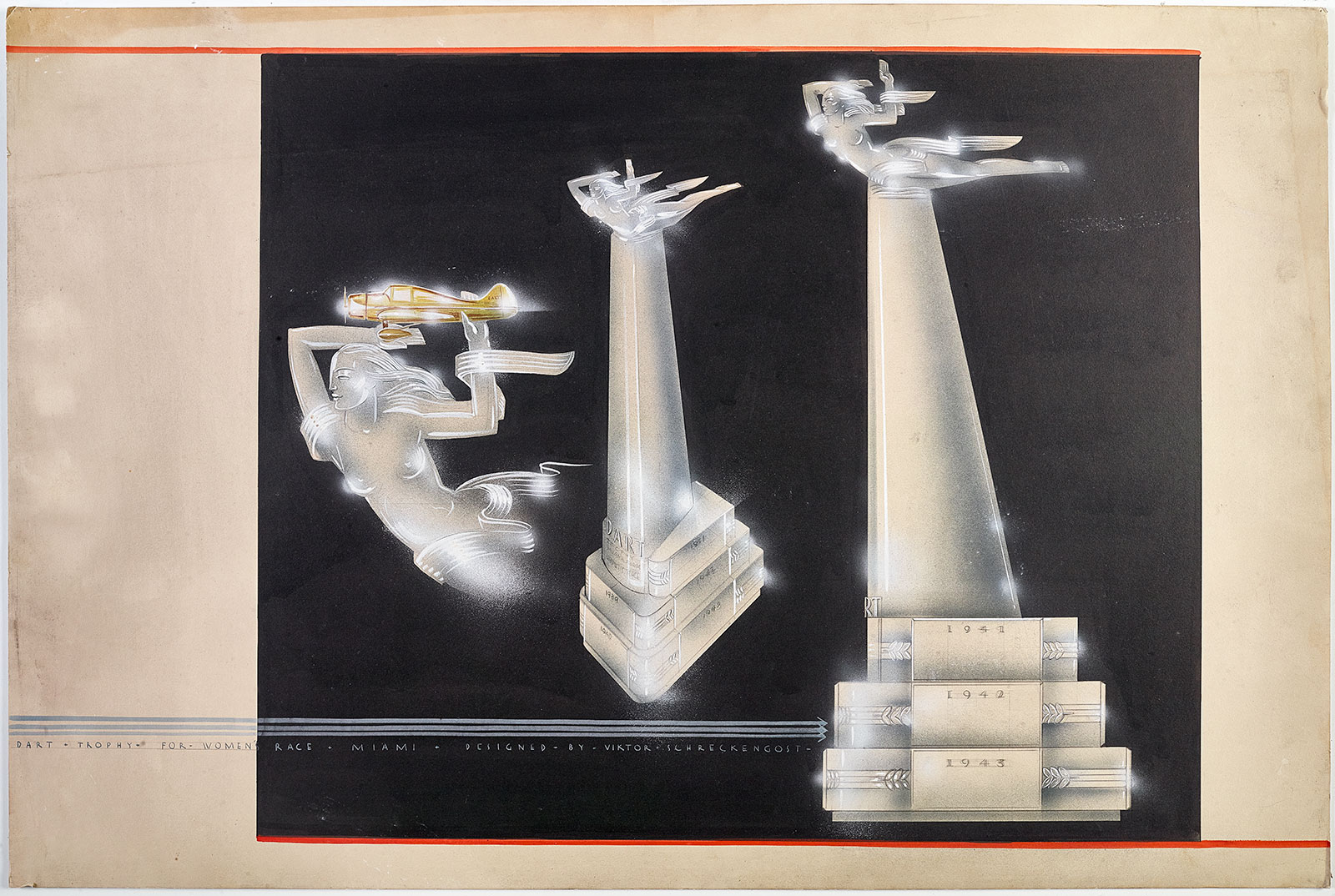

A record crowd of 18,000 gathered to witness nurse-turned-aviator Edna Gardner Whyte win a new race for female pilots—the Women's Sportsman Free-For-All—at the 11th annual All-American Air Maneuvers. The race was known as the K. K. Culver Trophy Race for the spectacular Art Deco trophy designed by industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost and commissioned by Knight K. Culver, maker of Dart airplanes. The trophy, now part of the Wolfsonian collection and on view in our current exhibition Aerial Vision, was described in the official program as "of strictly modern design, depicting the feminine spirit of flight, restless even in repose, mounted upon a symmetrical shaft."

Schreckengost was one of the most influential industrial designers of the 20th century as well as a prolific maker known for sculpture, ceramics, drawings, and paintings. His Jazz Bowl series for Cowan Pottery was famously first commissioned by Eleanor Roosevelt as a gift for her husband. He went on to design everything from electric fans and printing presses to lawn mowers. His streamlined Mercury Pacemaker bicycle for Murray Ohio Manufacturing company was launched as the "official bicycle" of the 1939 New York World's Fair. He taught industrial design at the Cleveland Art Institute for 50 years and late in life was awarded the National Medal of Arts—the highest honor that can be bestowed on an American artist by the United States government.

After learning that his work was in the collection of The Wolfsonian–FIU, Schreckengost traveled to Miami from Cleveland in 2006—at the age of 100! Wolfsonian exhibition designer Richard Miltner, who had studied at the Cleveland Institute of Art during Schreckengost's tenure, escorted him through the building, taking him to see his trophy and our collection storage. Miltner remembers Schrekengost's impact, not only on the industrial design department but also the entire Cleveland Institute of Art family: "He was the best combination of designer, teacher, and mentor."

During his visit, Schrekengost donated two proposal drawings for the trophy that provide important details, one clearly depicting a small detachable airplane to be held in the hands of the female figure that was intended to serve as the annual keepsake award. While this element was missing from The Wolfsonian's trophy at the time of its purchase and remains lost, hope remains that it will reappear in the future when someone realizes the connection.

The All-American Air Maneuvers and the K. K. Culver trophy embody the energy and enthusiasm surrounding aviation in Miami in the early 20th century. It is interesting to consider how these air-minded aspirations helped shape today's South Florida. Both in their earliest phases of development, South Florida and aviation co-existed, growing and evolving on parallel tracks. With the availability of large tracts of flat, undeveloped land and a wide protected bay for landing sites as well as its year-round good weather, South Florida was an ideal location to lure this new industry. Over the years, South Florida became home to major airlines and related businesses as well as serving as a key training site for the First and Second World Wars. Today, 111 years after that first airplane sighting, the region is a recognized hemispheric hub, its airport among the busiest in the world, providing more flights to South America and the Caribbean than any other U.S. airport. Mr. Sewell and his fellow citizens would be astounded.

For more on the K. K. Culver trophy, the Miami race, and Whyte, watch our Sky High lecture co-presented with Miami Design Preservation League for Art Deco Weekend 2020.

To see the trophy and other related items on display, visit Aerial Vision through April 24, 2022. The exhibition explores how aviation and skyscrapers, in making accessible the aerial view, transformed the way we see, experience, and interpret the world.

[1]The Miami Herald, January 8, 1931, May 27, 1911, Page 12.

[2]The Miami Herald, July 22, 1911, Page 4.

[3]The Miami Herald, January 8, 1931, Page 5.

[4]The Miami News, December 10, 1939, Page 46.