February 28, 2022

Augusta Savage’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing”

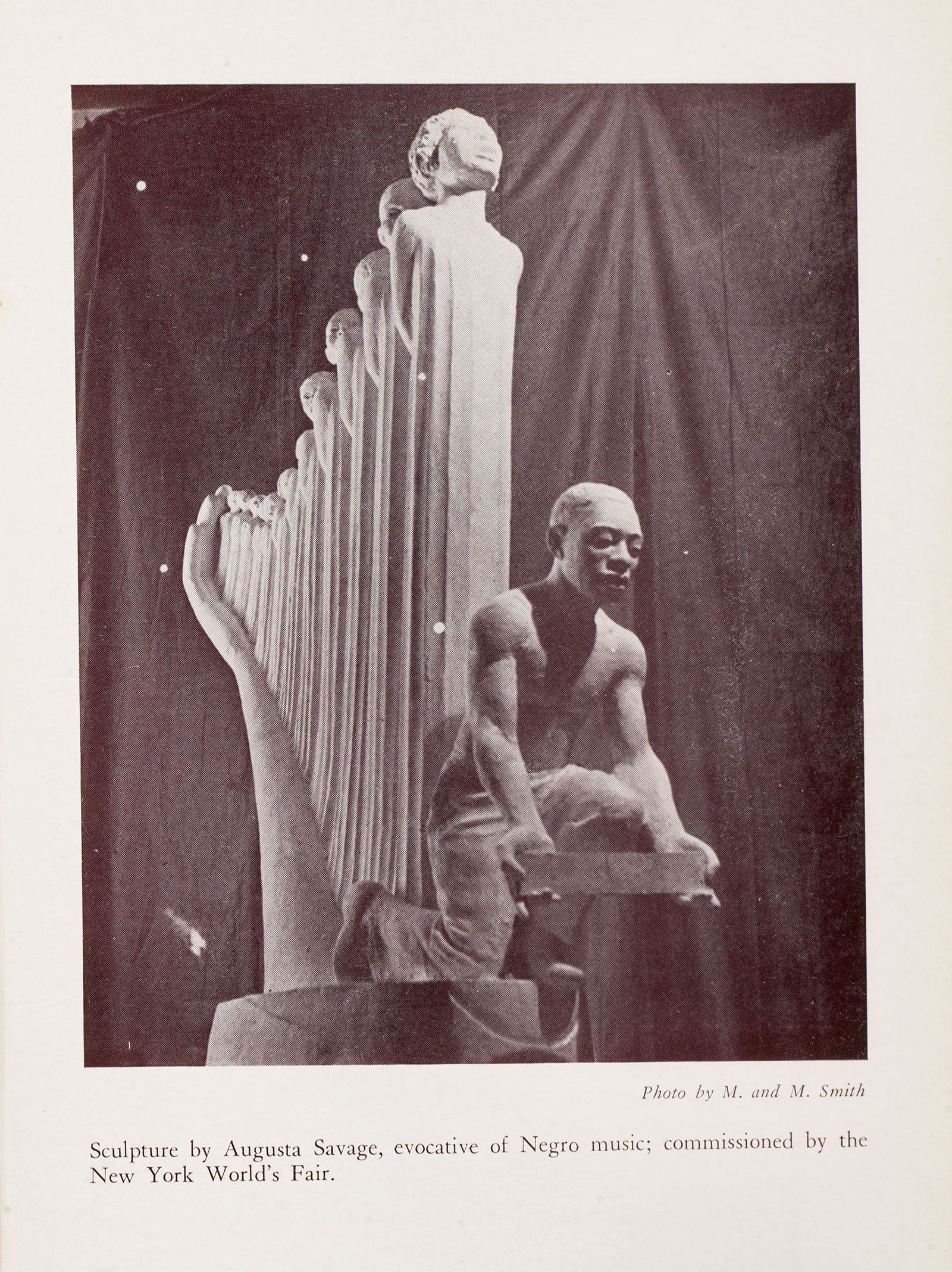

Book page, "Sculpture by Augusta Savage, evocative of Negro music; commissioned by the New York World's Fair," from Harlem: Negro Metropolis, 1940

Augusta Savage (American, 1892–1962), sculptor

Morgan Smith (American, 1910–1993) and Marvin Smith (American, 1910–2003), photographers

Claude McKay (American, 1890–1948), author

E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc., New York City, publisher

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Historical Design, New York City, XC2019.02.1.12

An intriguing image of a sculpture appears in Jamaican American poet and writer Claude McKay's 1940 publication, Harlem: Negro Metropolis. A narrative on the history of Harlem and its most notable African American residents, the book includes photographs taken by Morgan and Marvin Smith, twin brothers who studied under Black artist Augusta Savage in the early 20th century. Their photographic portrait of what is a likely a maquette of her monumental work for the 1939 New York World's Fair, Lift Every Voice and Sing, remains a rare material artifact of a fair centerpiece since lost to time, and a clue to the importance of her high-profile commission for American culture and Black artistry.

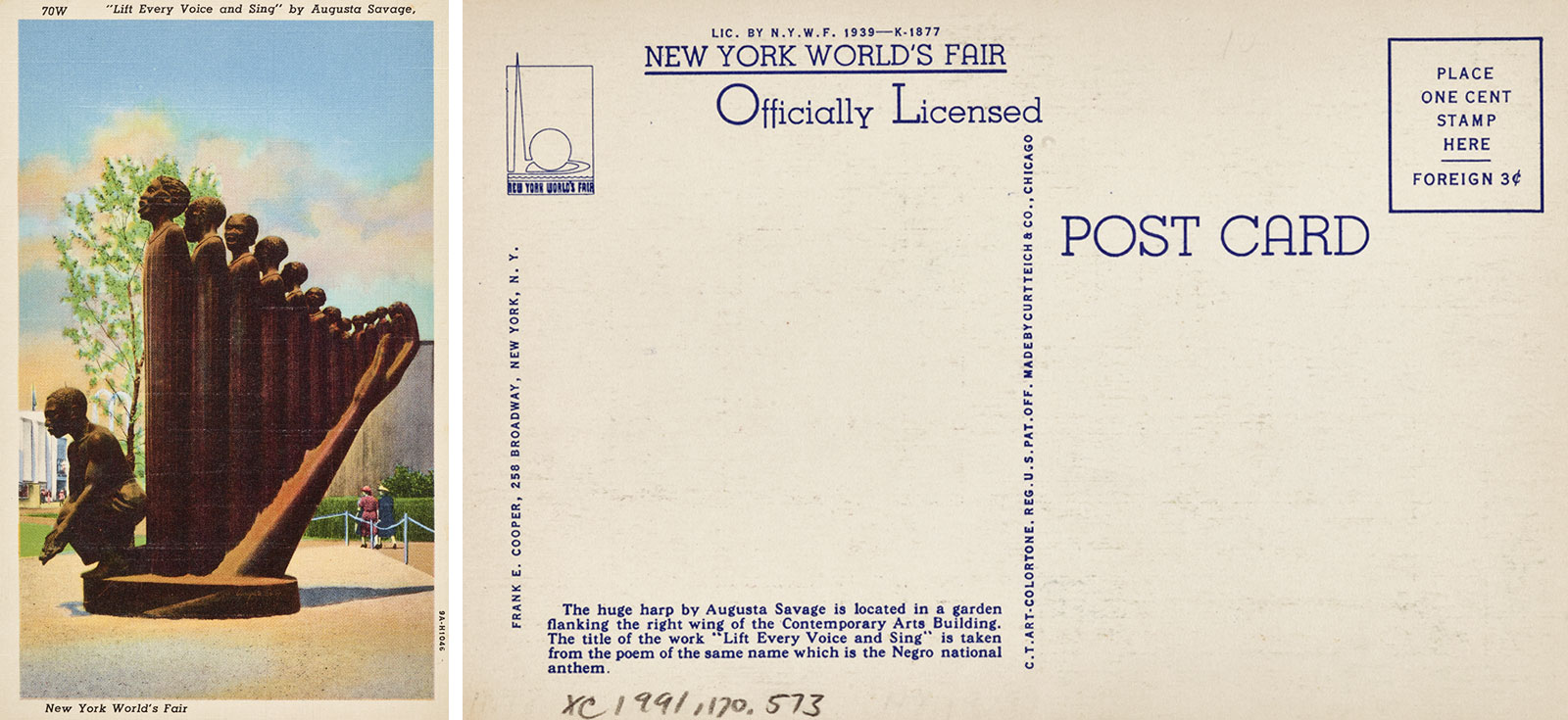

Standing at 16 feet in height and one of only two works by African American artists featured in the exhibition, Savage's plaster sculpture took its name from James Weldon and J. Rosamond Johnson's "Lift Every Voice and Sing," a hymn of particular meaning within Black communities. Savage modeled the piece after themes found in the song—unity, perseverance through faith, and pride, all of which are reflected in her musical scene. The harp's form is defined by a long arm and hand cradling 12 singers in choir robes, their strong stance and the folds of their garments evocative of strings. A young man kneels in the lead holding sheet music and carrying a pensive expression on his face, uplifted (we imagine) by the beautiful melody and the image the eponymous hymn's words recall.

"The Harp," as it became known, was a major achievement for Savage. Born Augusta Christine Fells in Green Cove, Florida, February 29, 1892, she was raised by a Methodist minister who opposed her creative interests. Over her father's objections, Savage returned again and again to sculpture throughout her youth and—after marrying, having a child, and becoming widowed by her early 20s—committed her focus to the arts and moved to New York City with less than $5 in her pocket. Savage quickly became a recognized talent in the art world and a vocal advocate for equal rights, generating media attention when an American selection committee revoked her award of a summer study-abroad scholarship to Paris because of her race. Defying these obstacles, Savage self-funded and completed a 4-year arts degree at The Cooper Union in 3 years, fundraised for her own trips to France to exhibit at prestigious sites like the Salon d'Automne and Grand Palais, and earned an array of accolades ranging from a Carnegie Foundation travel grant to the distinction of being the only African American member admitted into the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. By 1937, the 1939 New York World's Fair Board of Design reached out to her with the idea of a large-scale sculpture symbolizing the legacy of African American music.

Though 44 million guests had the chance to witness and admire Savage's triumph at the 19-month exhibition, unfortunately the work was destroyed when the fair ended, a scenario not uncommon for temporary works and pavilions. Promotional postcards and documentary photos like the one in McKay's book, however, paint a picture of the song and sculpture's true impact and continued resonance. Today, "Lift Every Voice and Sing" is still widely celebrated as the "Black national anthem" (recently and memorably performed at "Beychella") and metal replicas of Savage's 1939 tribute—a testament to the inspirational power of the Black church and indomitable nature of the human spirit—are held in collections such as those of the Schomburg Center in Harlem and Columbus Museum in Georgia.

– Carlos Ascurra, FIU Humanities Edge curatorial intern