January 17, 2022 (Martin Luther King, Jr. Day)

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

January 17, 2022 (Martin Luther King, Jr. Day)

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

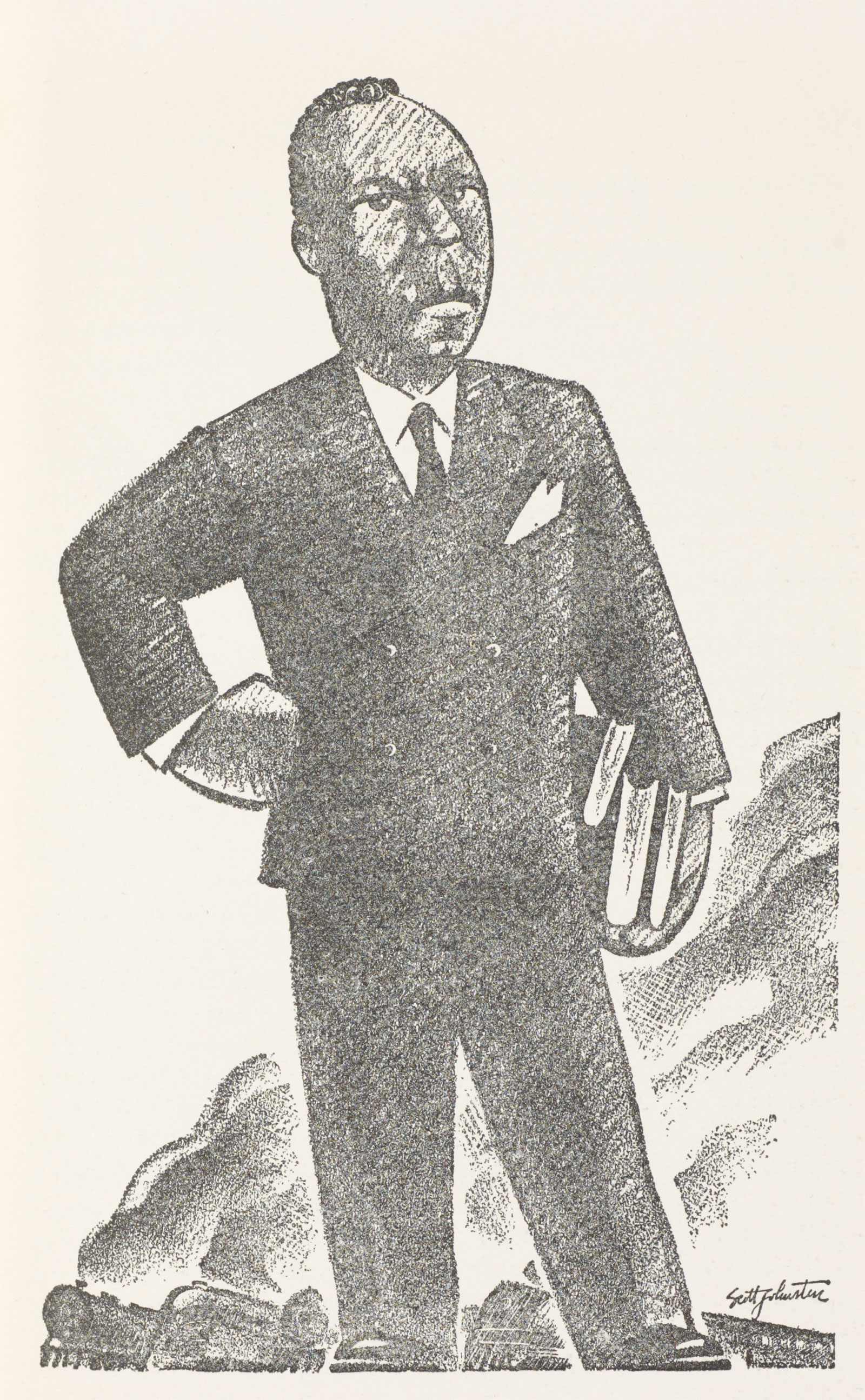

Book illustration, "A. Philip Randolph," from Men Who Lead Labor, 1937

Scott Johnston (American, 1903–1982), illustrator

Bruce Minton (pseudonym for Richard Bransten, American, 1906–1955) and John Stuart (pseudonym for Jacob Winocur, American, 1912–), authors

Modern Age Books, Inc., New York City, publisher

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Christopher DeNoon Collection for the Study of New Deal Culture, XC2010.09.7.135

As we commemorate the birthday of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., many of us conjure up the sights and sounds of his 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered near the Lincoln Memorial and broadcast live across the nation. A crowd of more than 250,000 civil rights activists attended the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, an event that helped spur the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the National Voting Rights Act the following year. Before listening to King's address, the participants first heard from other speakers, including the march chair and organizer, Asa Philip Randolph.

Featured in the 1937 publication Men Who Lead Labor, Randolph—a former editor and publisher of the influential African American magazine Messenger and head of the all-Black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters—recognized that the Second World War's outbreak in Europe would create a manpower shortage in defense industries, increasing the demand for Black workers and offering leverage in the fight for civil rights. To convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to support ending discrimination in this highly segregated sector of the economy, Randolph began organizing a March for Jobs aimed at bringing 10,000 peaceful protestors to the capital. The response to his outreach was overwhelming; ten times that number were expected to participate.

President Roosevelt met with Randolph hoping to forestall the demonstration, concerned that an anti-discrimination march would embarrass the administration. As a result of their negotiations, the President banned racial discrimination of industry and government workers via executive order and created the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to investigate incidents and enforce compliance with the new policy. Randolph agreed to call off the march with these goals achieved, and due to his pressure on Roosevelt, the number of African Americans employed in defense industries and government jobs increased threefold by 1945.

Congressional committees defunded the FEPC after the war's end, and another 20 years would pass before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission—still in place today—would be empowered to combat workplace discrimination. Randolph never ceased advocating on behalf of civil rights, and his plans for a March for Jobs demonstration in the nation's capital lived on. The next generation of civil rights activists (including King) built on Randolph's success with nonviolent action and pressure tactics, securing major progress in civil rights and creating a blueprint for protest and change for decades to come.