October 7, 2021

By Molly Seghi, Museum Studies Intern

There is no image more compelling to me, an avid wearer of a "We Can Do It!" sweatshirt and owner of a Liberty Leading the People phone case, than an empowered woman during wartime. Surrounded by historic propaganda during my Wolfsonian summer internship, I came to consider what these images might have meant to women at the time. In particular, I examined First and Second World War artwork used to remind the nation that women played an irreplaceable role in these war efforts.

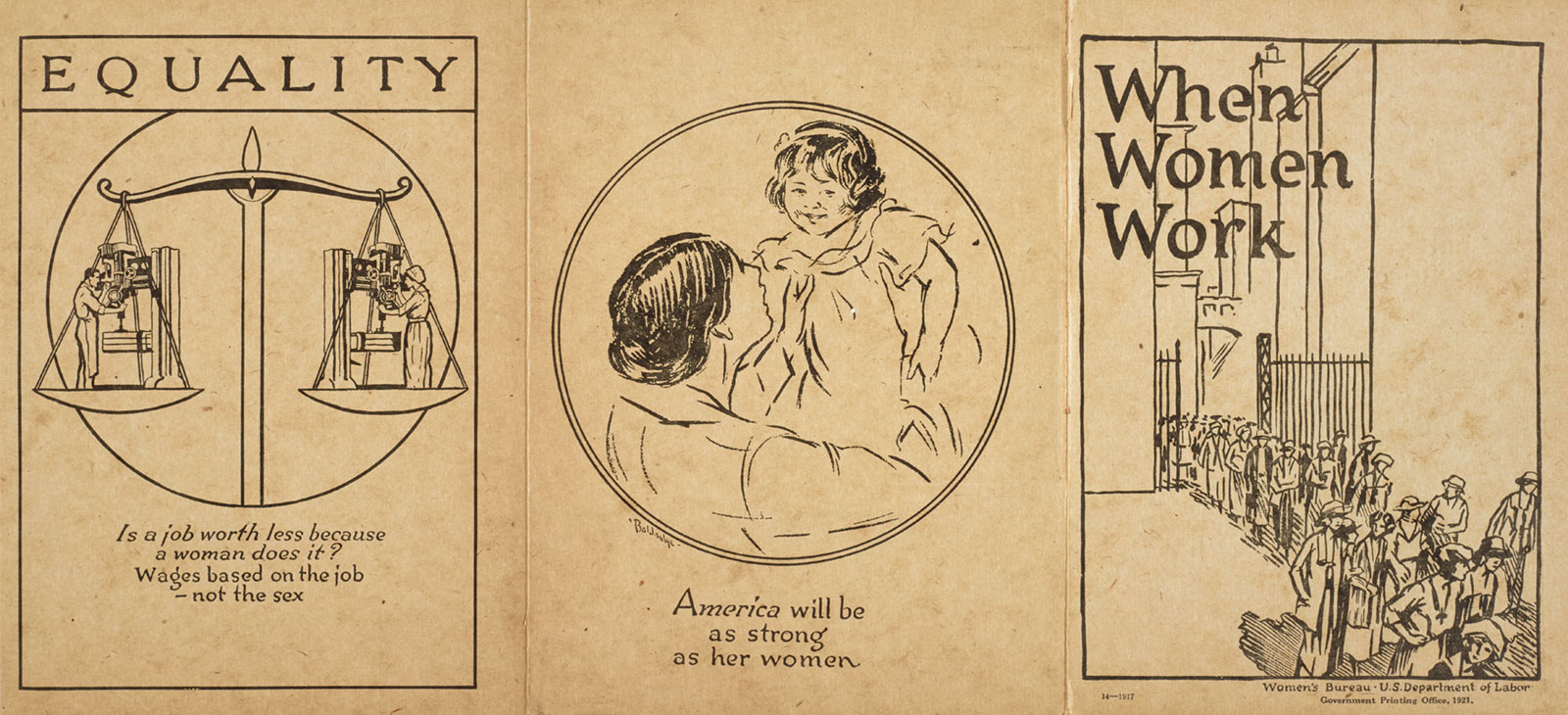

In the late 19th century, as women's access to college education and wages grew, the idea of the New Woman emerged, reshaping what roles society determined were proper for women. Independent, well-educated, and white, the New Woman redefined what femininity and masculinity meant in American culture by advocating for the growth of women's political and legal rights, however progress proved slow and it was rare for a woman to have true political and economic independence. While the women's suffrage movement made important gains in 1914 when 8 states began recognizing women's right to vote, universal suffrage remained elusive. Suffragettes were commonly dismissed as masculine and aggressive, culturally frowned-upon traits that were in contrast with the traditional ideal of women as feminine beauties and mothers.

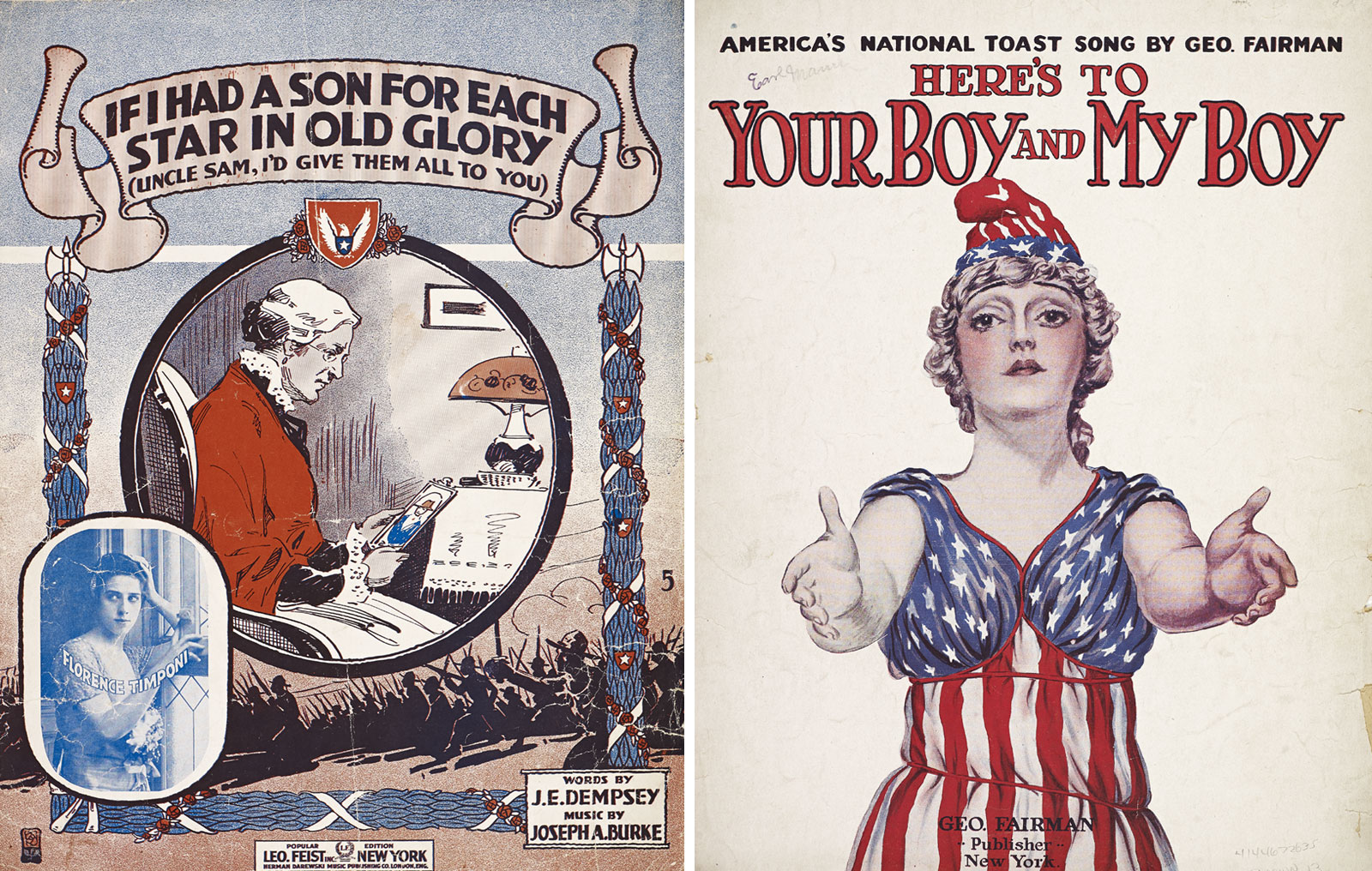

During the First World War, gender roles did not fundamentally shift, but rather readjusted to meet the needs of wartime. War created a situation in which men tested their masculinity in combat while women were expected to retain their traditional roles as kind-hearted homemakers waiting for their soldier husbands, fathers, and brothers to return. To spur patriotism and cheer on the fighting men, images on materials like posters and sheet music covers portrayed women as gentle sweethearts, mothers, and saviors—sources of comfort and encouragement for those protecting the homefront.

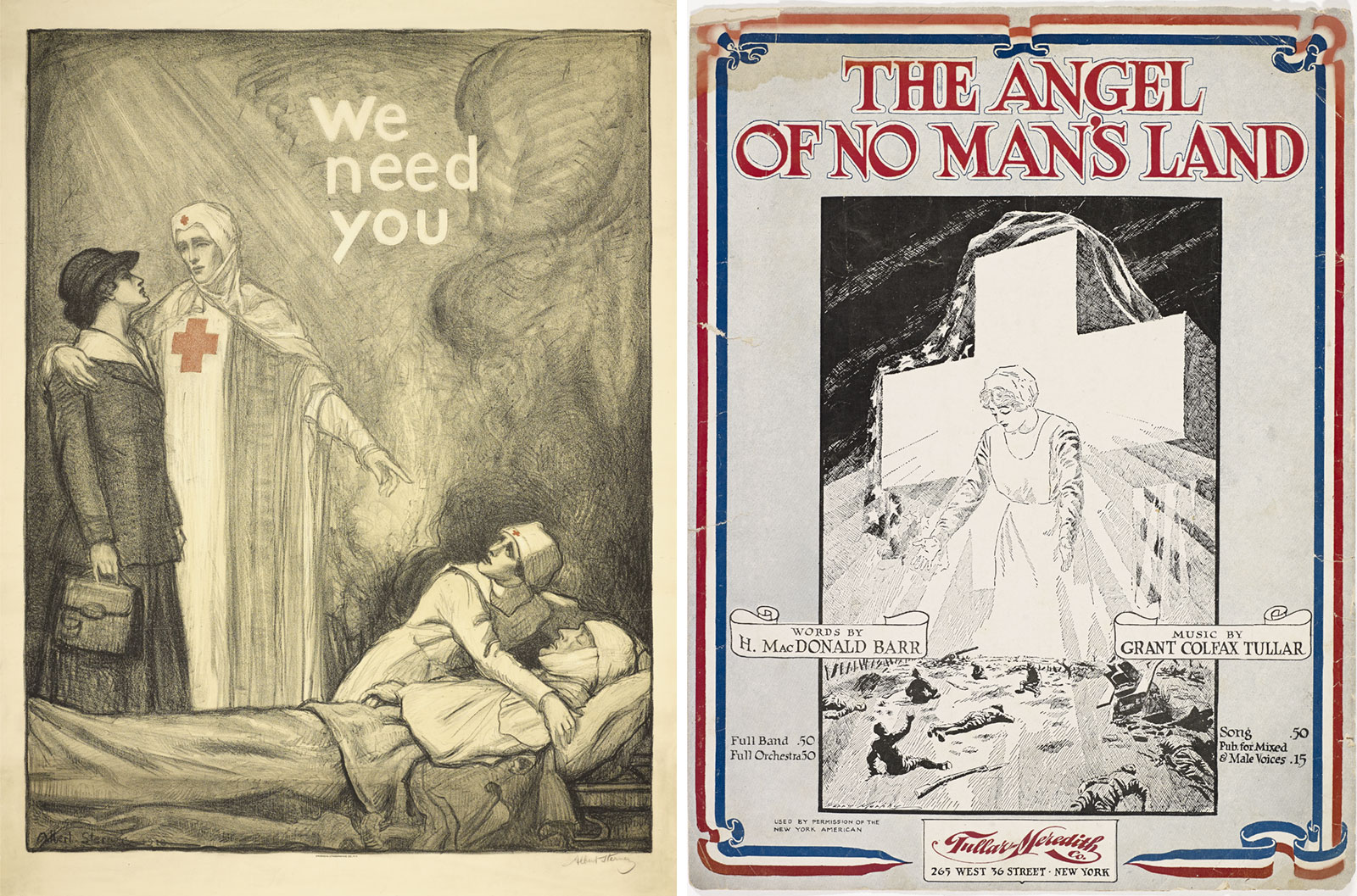

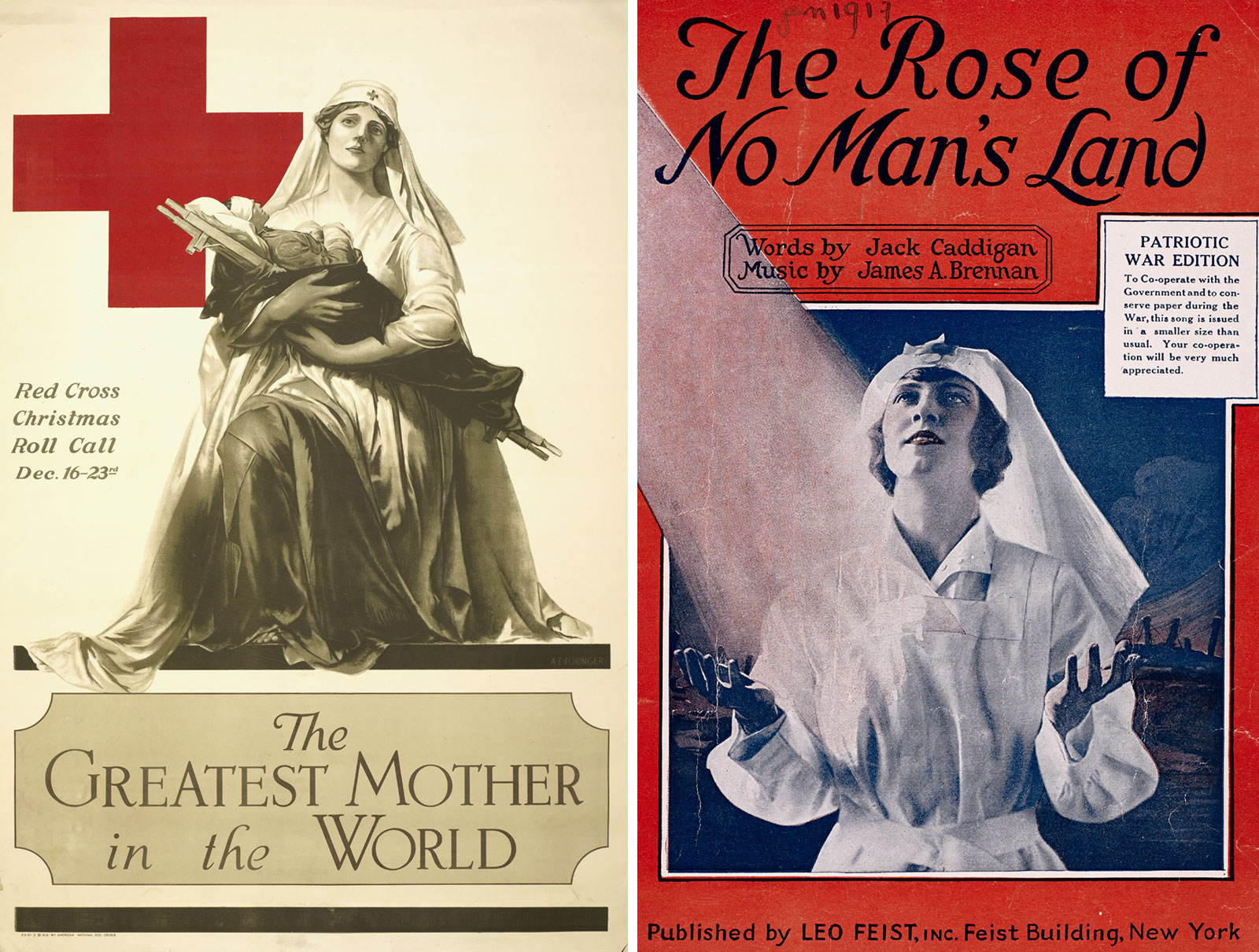

Because of the growing need for traditionally women-dominated roles such as nurses, women began working as unpaid laborers who volunteered their time and efforts to the Red Cross, some even traveling overseas as health workers. The cultural shift of women becoming the "protectors" and "saviors" of men, who were presented as fragile and in need of salvation, created a blurred line between masculinity and femininity and inspired a new double identity for nurses that bordered on celestial. To recruit female nurses, the Red Cross produced posters advertising the position as charitable, patriotic, and necessary, without breaking through gender-specific markers of domesticity and femininity. As reflected in the 1918 poster We Need You, the nurse form shifts to one more angelic and sexless, her robe erasing her feminine figure and hair. Her hands, welcomingly open, illustrate the continuity of acceptance and grace radiated by women, while their larger size evokes new strength and power. In comparison, The Greatest Mother in the World presents the Red Cross nurse in a more maternal light, with its more feminine-appearing subject shown cradling the wounded as a mother would a child.

The First World War also saw seismic shifts in factory workforce demographics, which further muddied the boundaries of conventional roles and created a new sense of gender fluidity. To cover the jobs left behind by soldiers and to help production during the war, women began entering the factory and wearing the more androgynous clothes required by physical labor. In For Every Fighter a Woman Worker, we see a middle-class woman proudly wearing this uniform—plain and utilitarian in style, with roomy pants and rolled sleeves for easy movement. Counteracting this masculinity and reassuring women that their femininity would not be compromised by demanding and dirty work, the poster shows her as a classical beauty, young and without a touch of grime.

Following the First World War, more women entered the workforce than ever before, though often as domestic workers or in feminized professions such as schoolteachers and nurses. Unlike men, they hadn't earned military or veterans' benefits for their wartime contributions, and thus they were prohibited from enjoying political freedom; meanwhile, the nature of marriage started to change during the Flapper era as access to birth control gave women more freedom in their personal lives. As my history teacher would say, this "pendulum swinging" of the immediate postwar period came to a stop when the Great Depression hit—once again, men were primarily the breadwinners and received priority for scarce jobs. This did not last long, as the Second World War had different plans in mind.

The success of women working at the homefront during the First World War primed the pump for the Second World War, when the number of men needed in combat quadrupled from about 4 million to 16 million. Propaganda posters from this time—which mobilized middle-class women as the new temporary faces of the workforce by appealing to their patriotism and emotion—reflect society's newfound conditional acceptance of women in the workplace.

The More Women at Work the Sooner We Win! promised women that their contributions could bring their men home faster. The woman embodies the desire to retain femininity in the workplace through painted polish and red lips. Although she is doing major factory work, she is still perfectly put together, even wearing jewelry that could prove dangerous among industrial machines. Another example of this idealized, ladylike laborer is my personal favorite, Rosie the Riveter, a romantic and heroic figure who has become one of the most popular icons of female empowerment. Rosie made her first appearance in Norman Rockwell's painting on the cover of a May 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post; there, the muscular riveter was depicted casually desecrating Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf, which brewed concerns about fluctuating gender roles. In response, Howard Miller created the famous We Can Do It! poster illustrating a feminized and attractive Rosie who was bold, but not too confrontational.

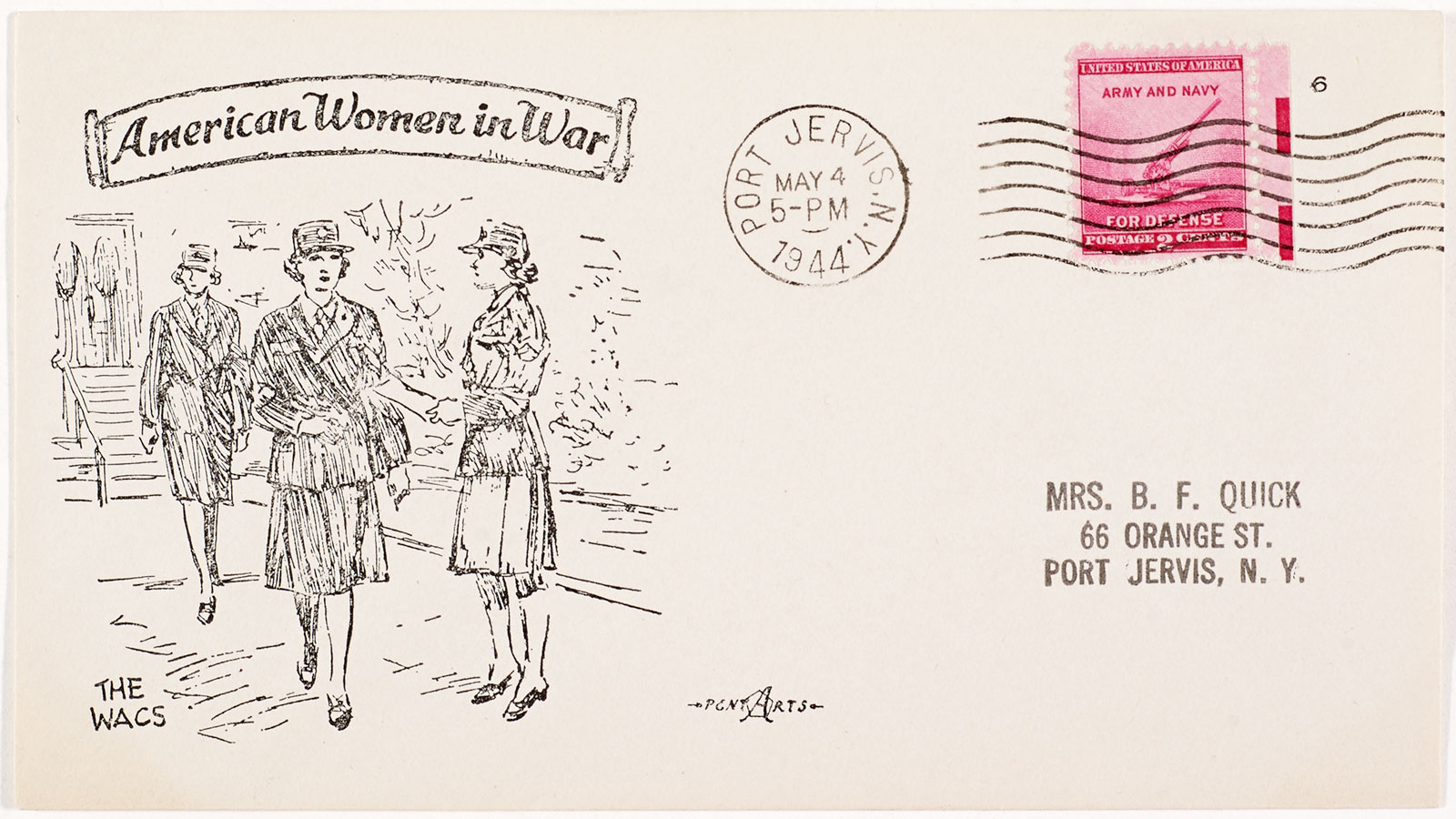

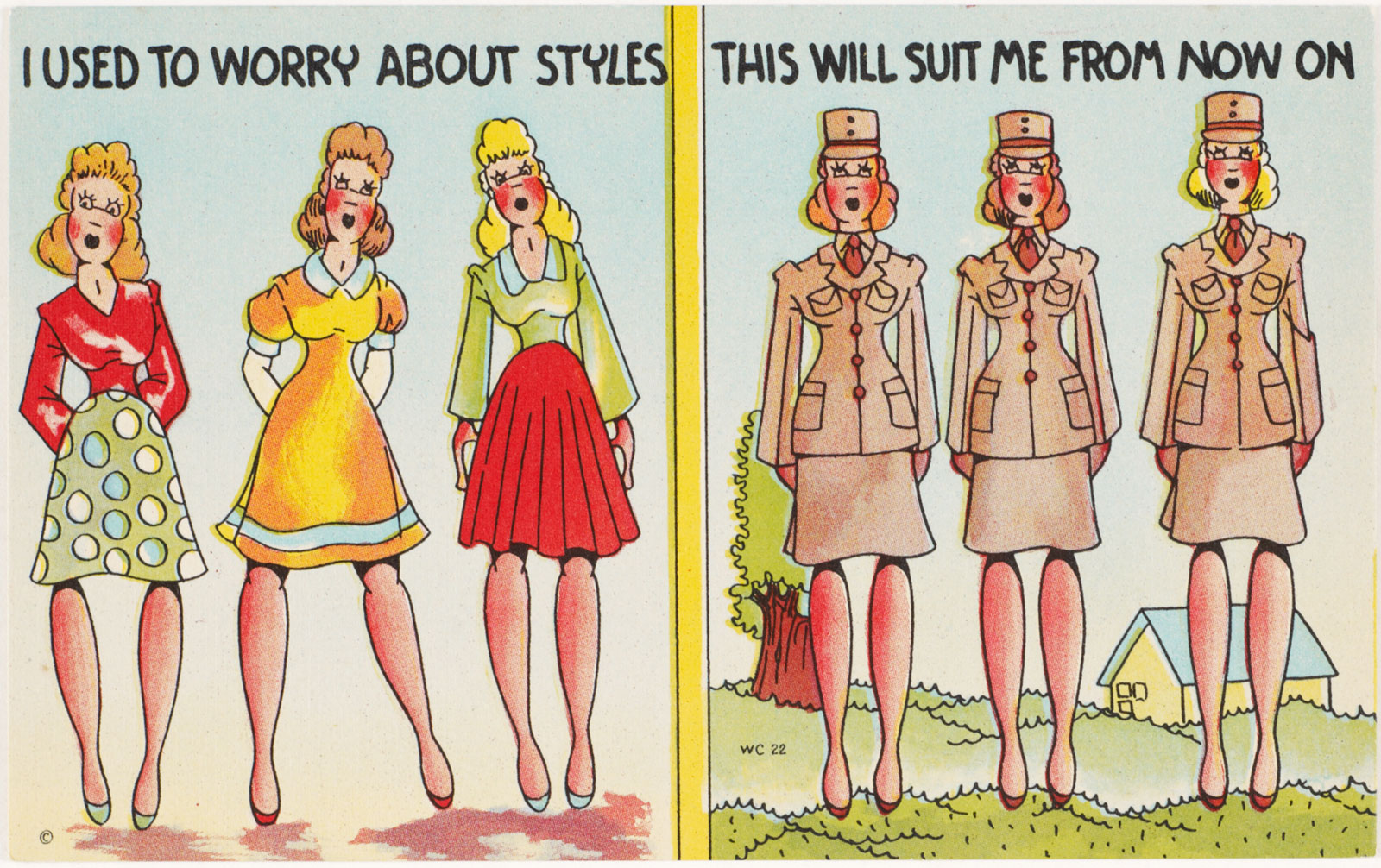

Nationally, there was an understanding that these women's jobs were temporary. WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and WAAC (Women's Auxiliary Army Corps) both allowed women to serve their country, but they also made it clear how their services were "auxiliary" and needed for an "emergency" only. Promotional campaigns to bring women into the workforce were successful, resulting in an increase from 12 million to 16 million women in less than 4 years.

However, as the number of women in the labor market swelled, social problems arose, such as heightened demand for childcare and the new pressures of balancing housework, employment, transportation, and raising a family. Nevertheless, working women tried (mostly unsuccessfully) to keep their jobs after the war—though layoffs, demotion in rank and pay, and outright firings all but eliminated women from their wartime positions. Instead, they were employed in pink-collar jobs such as secretaries or waitresses. There was a clear shift in the zeitgeist, as women were encouraged to get back into the home—magazines began focusing exclusively on suburban life, pushing advertisements marketing state-of-the-art home appliances designed to make the life of a homemaker easier and more efficient.

Although the urgency for women in the factories diminished and advertisements began to focus on homemaking, more women than ever before entered the peacetime workplace in the 1950s. They did not receive support or attention on any scale nearly like that of the war years, but the new phenomenon of a woman with a family and career continued to expand and grow (baby steps).

As a nation, we have come so far in terms of advancing women's rights and creating more inclusivity in the workplace and in the media. Growing up in the age of social media with a phone in my hand, I have trained myself to be a skeptical consumer of the media, because just like in these images, there is always an underlying motive (stream my podcast Love Yourself Without Likes on any podcast streaming service to hear more.) It is vital to be conscious of what information you are being fed, whether negative or positive, and the purpose it serves. Every day, I think about how grateful I am for the pioneering women who have made strides in creating greater equality, and I have made it a life goal to follow in their footsteps. It is important to appreciate how far we have come, but also recognize that there is much work we still must do.