September 18, 2021

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

Just this week, the ultra-popular Broadway productions of The Lion King, Hamilton, and Aladdin reopened to the public after an 18-month hiatus occasioned by the coronavirus pandemic. The financially ruinous closings and hopes for a revival in the fortunes of Broadway are not unique to our times—they are, in fact, reminiscent of earlier struggles endured by the producers of live theater, vaudeville, and Broadway musicals.

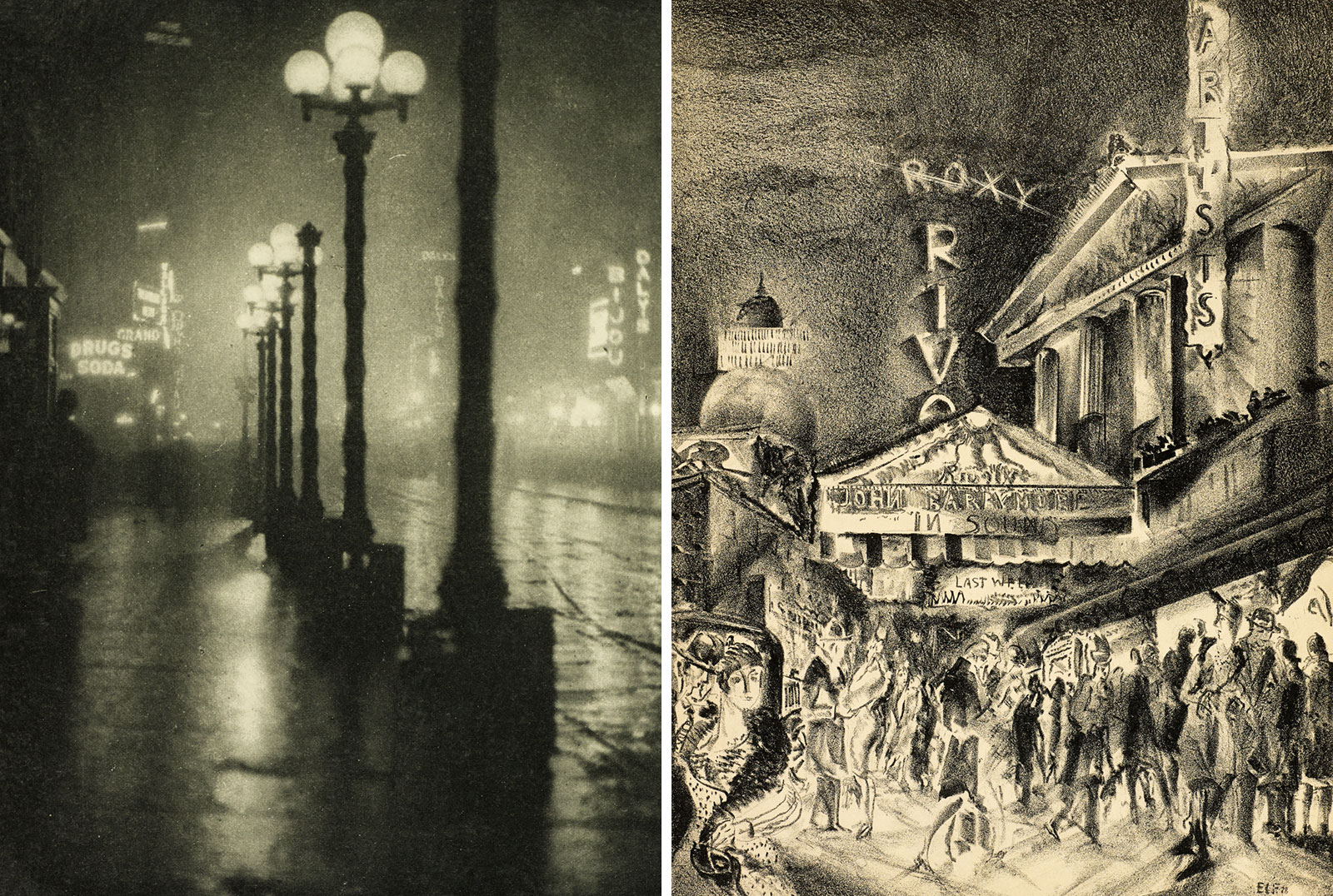

It was during the last decade of the 19th century that Oscar Hammerstein first opened the Olympia theater even before streetlights had been installed on Broadway. In illuminating the façade and marquee of his grand theater with brilliant electric lighting, Hammerstein started a trend taken up by so many other theatrical producers that the area gained international fame as the "Great White Way."

The Broadway theater district would flourish in the decades that followed. As America entered the First World War, war-themed musicals and plays swept Broadway, with even the Ziegfeld Follies patriotically wrapping themselves in the flag. The simultaneous spread of the dread Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918/1919 forced the closure of theaters and public entertainment venues across the nation, with one exception: New York's commissioner of health adopted a "keep calm and carry on" approach. He defiantly (and dangerously) refused to shutter the city's theaters, vaudeville shows, playhouses, and cinemas, believing that they were critical to maintaining morale in time of war and epidemiological crisis. The only concessions to the contagion were orders to stagger curtain times to cut down on crowding and to authorize ushers to remove (by force if necessary) "sneezers, coughers and spitters" from the audience!

Not surprisingly, Broadway venues experienced lots of empty seats in the worst days of the crisis, and the city witnessed steep spikes in new cases of the deadly flu. More than 20,000 New Yorkers would succumb to the influenza epidemic, though admittedly that number remained lower than rates in other large East Coast cities; more than 600,000 Americans would die from influenza or pneumonia nationwide.

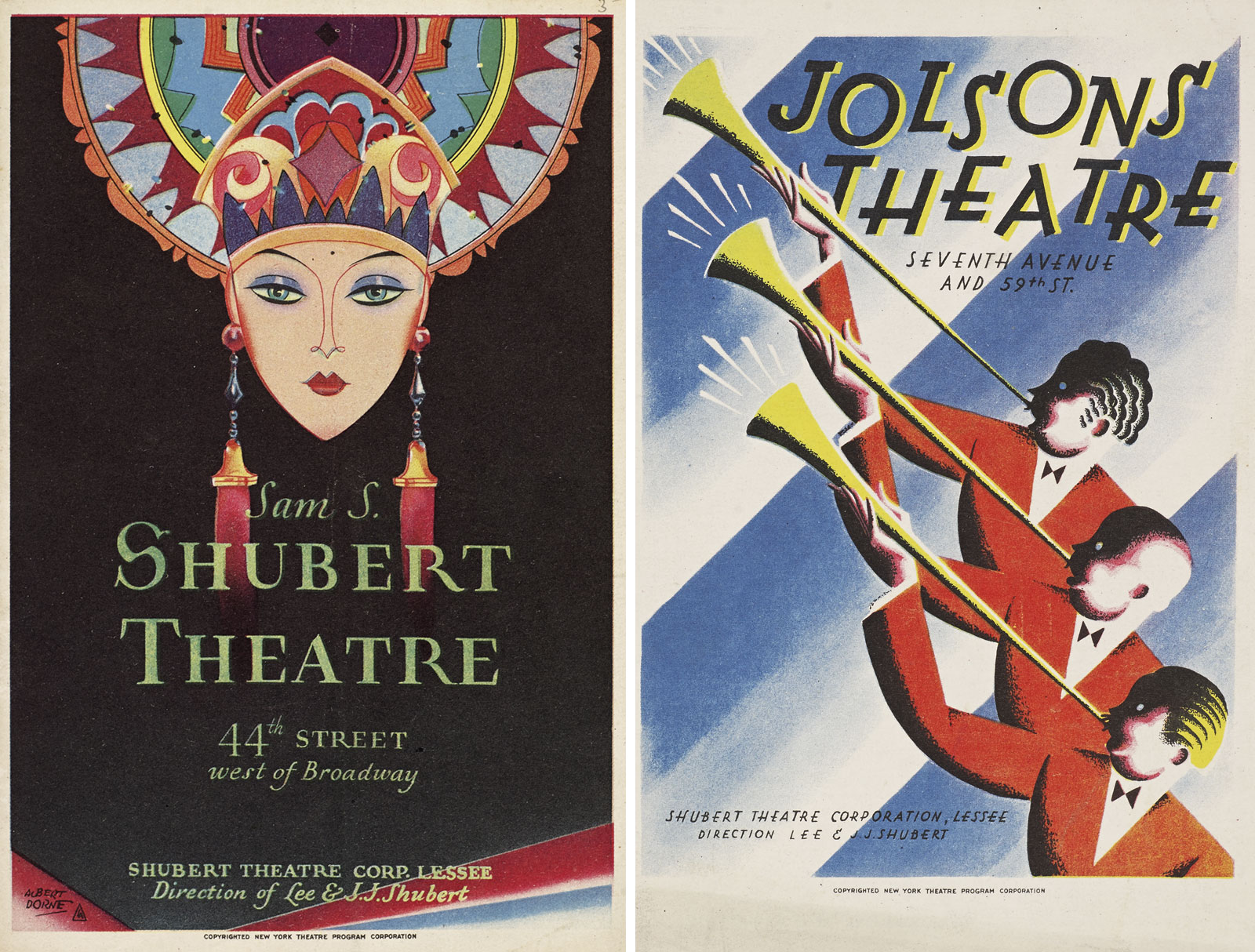

The October 1929 Stock Market crash had a far more devastating effect on Broadway than the 1918/1919 pandemic, bringing down the curtains of many major playhouses. During the decade-long depression that followed the crash, ticket sales dropped precipitously, leading to mass layoffs of actors, set designers, costume-makers, directors, and ushers, and to the bankruptcy and closure of many theaters. An indication of hard times, even the New York publishers of Theatre Magazine ceased printing their monthly in 1931.

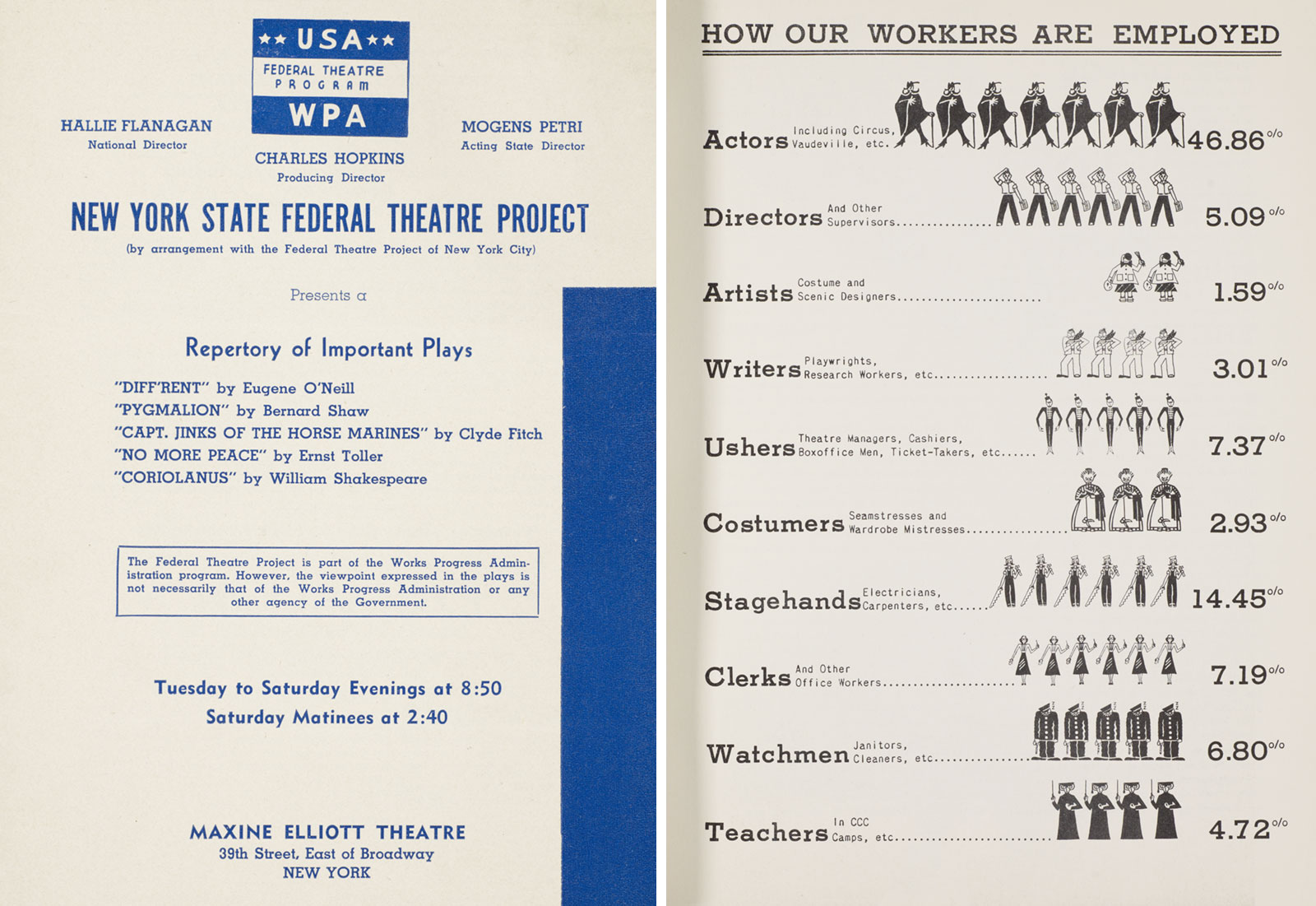

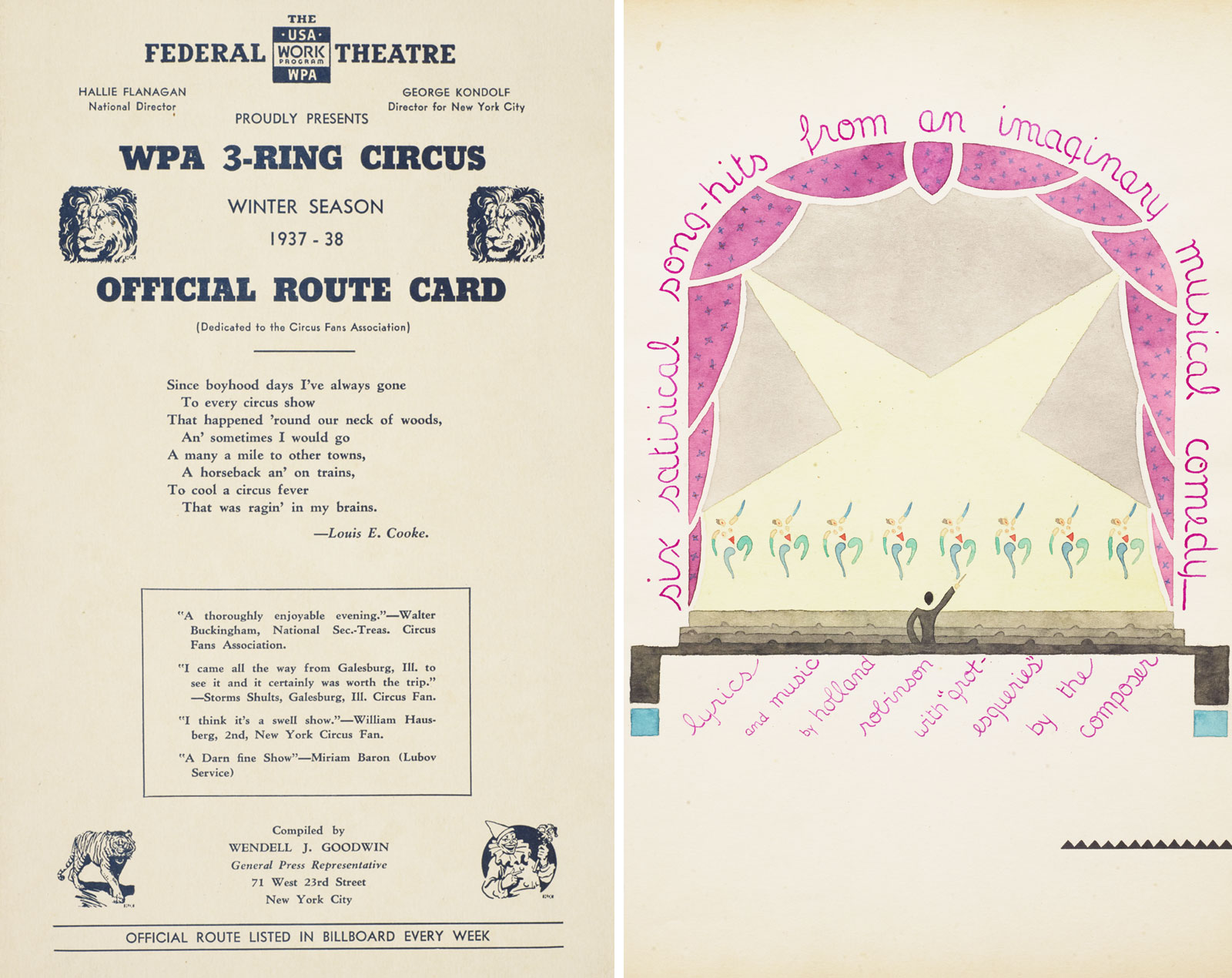

With so many theaters being shuttered up and turning off their lights, the Great Depression threatened to stamp out culture before Present Franklin D. Roosevelt's Federal Theatre Project came to the rescue. Between 1935 and 1939, the FTP reopened numerous theaters and employed 13,000 professional theater workers while producing 64,000 performances that reached an audience of 15 million.

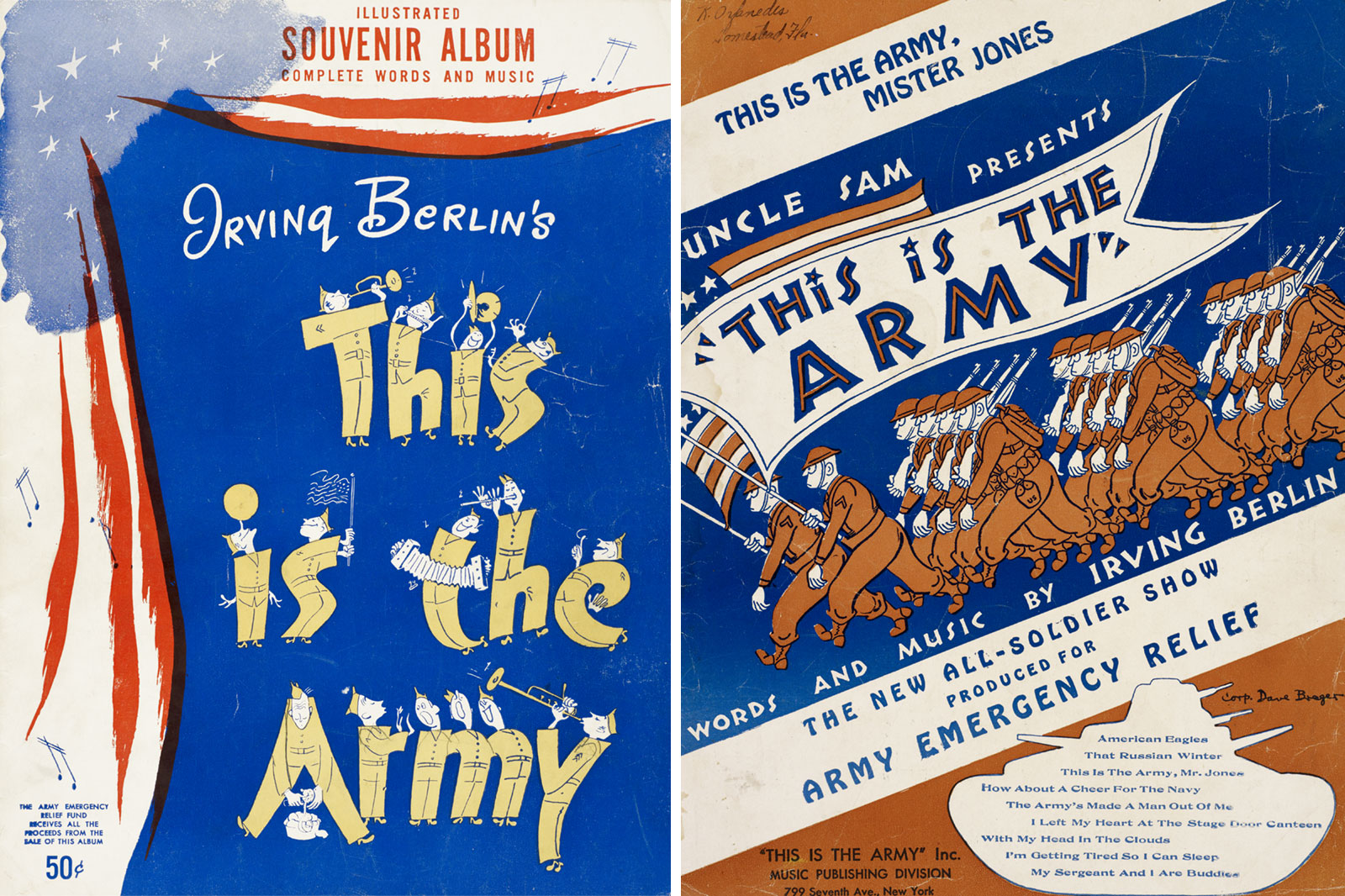

Overnight, the FTP's "negro" unit became the single largest employer in Harlem, where African-Americans typically suffered a staggering 50% unemployment rate. FTP productions included such diverse public events as circuses and marionette performances for children; popular Gilbert and Sullivan musicals; and serious dramatic adaptations for adults by ancient and contemporary playwrights such as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, George Bernard Shaw, and Eugene O'Neill. The legendary Orson Welles cut his teeth directing and performing in Federal Theatre Project plays. Broadway survived the Great Depression and flourished once more in the post-war era. As it had during the First World War, Broadway adapted to its sequel, producing a battery of patriotic musicals during the Second World War.

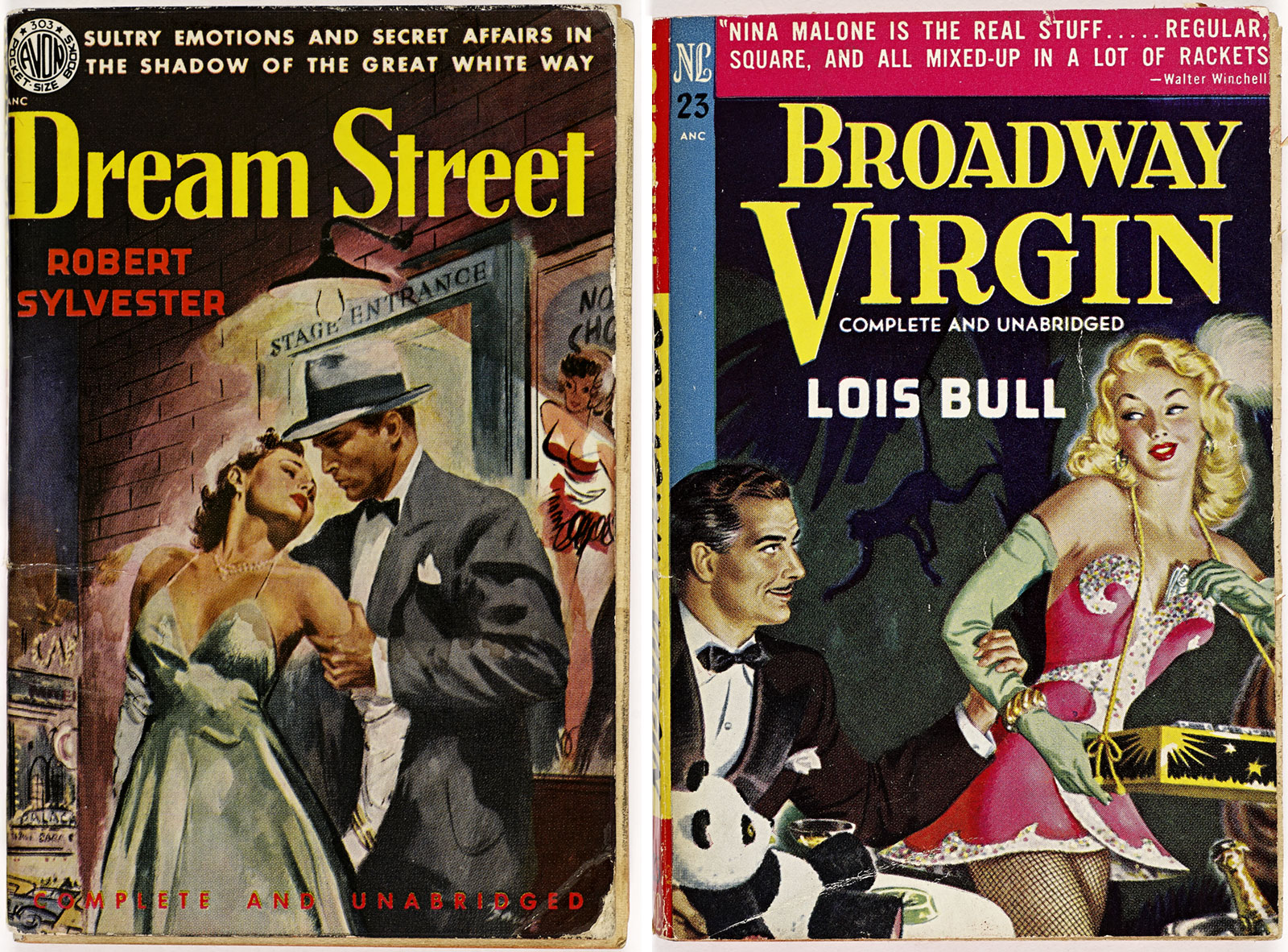

In the post-WWII period, Americans and tourists flocked once more to New York's most celebrated theater district, and Broadway even served as the setting and backdrop for salacious pulp fiction paperbacks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed the latest challenge to Broadway. Even as the live theaters and musical venues are beginning to reopen, theatrical producers, performers, and the public are keeping an eye on the fast-spreading Delta variant. We can only hope that the newest mutation of the virus does not derail and undo much of the progress made by adopting physical distancing, wearing personal protection, and getting vaccinated.