July 28, 2021

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

The scene: In the summer months preceding a presidential election, demonstrators peacefully protesting in the nation's capital are dispersed with tear gas and routed from the area by armed, uniformed men. When the air clears and the news media question the Republican incumbent as to the necessity of such force, the president states that he was acting in defense of law and order and denounces the protestors as a violent and dangerous rabble.

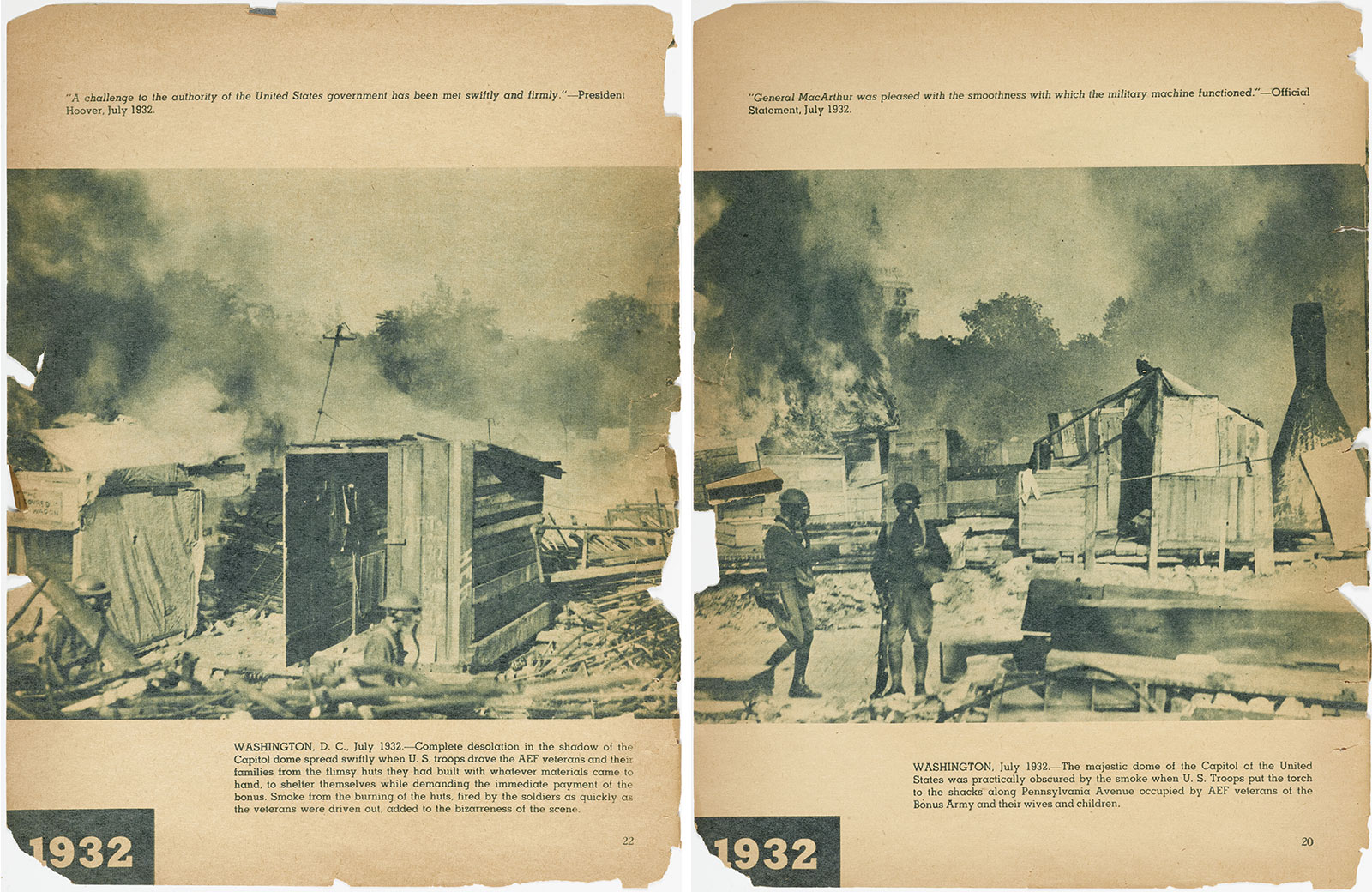

You might be surprised to learn that this describes an event from almost 90 years ago today—and not the clash between racial justice activists and police at Lafayette Park on June 1, 2021. An eerily similar incident occurred on July 28, 1932, when President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army to disperse the Depression-strapped First World War veterans who had gathered to ask Congress to pass legislation aimed at compensating their wartime service. The extreme use of force, the president's characterization of the veterans as "red" radicals bent on overthrowing the government, and the burning of the veterans' "Hooverville" (or shanty town) on the Anacostia Flats outskirts of the city did not help Hoover's bid for re-election.

The men who had either volunteered or been drafted into the American Expeditionary Forces in Woodrow Wilson's "War to End All Wars" had received considerably less compensation for their heroic service than the war industry workers on the home front. In response, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act in 1924 to provide veterans with a "bonus" based on their service records.

There was only one catch—the bonus certificates, deridingly nicknamed the "Tombstone Bonus," would only mature and be redeemable in full on each veteran's birthday in 1945. When tens of thousands of veterans lost their jobs and were evicted from their farms and homes as the Great Depression dragged on, many signed petitions pressing for an early payment of the bonuses. After President Hoover vetoed the Patman Veterans Bill in 1931, one unemployed vet, Walter W. Walters, living in Portland, Oregon, rallied local veterans and organized a trek to the nation's capital to lobby Congress directly and press for immediate disbursement.

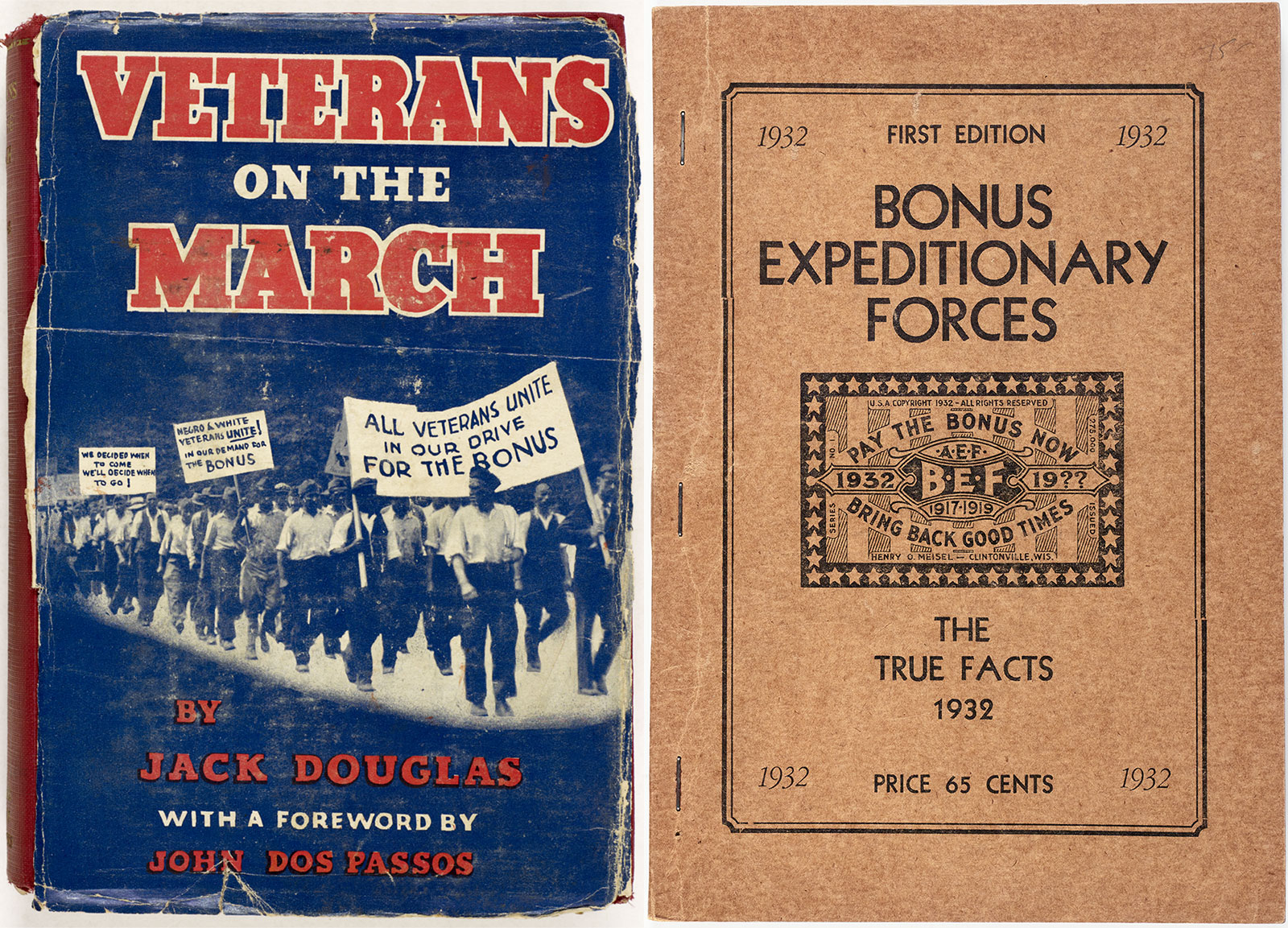

Dubbed the "Bonus Army" by the press, Walters's group inspired many thousands of ex-servicemen from across the nation—some accompanied by their families—to join his Bonus Expeditionary Forces, hop trains, hitchhike, and join the caravans descending on Washington. Arriving in Washington, D.C., in July 1932, the veterans camped out on the grounds of the Capitol building. As their ranks swelled into the tens of thousands, they established their makeshift camp.

While the House of Representatives passed a bonus bill, it looked unlikely that the Senate would approve it. On June 17, 1932, thousands of veterans gathered on the grounds of the Capitol building to maintain a vigil as the Senate was scheduled to vote on the legislation. The chants and an ironical rewording of a First World War tune "The Yanks Are Starving" could be heard in the Senate chamber even as that body overwhelmingly voted the bill down, with members beating a hasty retreat through back doors and underground tunnels under Congress to avoid facing the thousands of ex-servicemen loitering outside. Rather than greeting the disappointing news of the bonus bill's defeat with rioting, Walters led the veterans in singing "America the Beautiful" before peacefully disbursing.

Hoover expected and encouraged the veterans to vacate their squatter camp and "go home," and while many did pack up and go, thousands of veterans and their family members—jobless and homeless and without better options—remained. Walters and other veteran leaders also encouraged them to stay and continue to press for their bonus until the adjournment of Congress in July. Retired Major-General Smedley Butler visited the Bonus Compensation Army camp and had been impressed by the comradery of the campers and the orderliness of their tent and shack "city," which accommodated more than 11,000 and was democratically arranged in streets and blocks without regard to rank or race. Addressing the veterans, he told them that "It makes me so damned mad that a whole lot of people speak of you as tramps. By God, they didn't speak of you as tramps in 1917 and 1918." Telling them that they had "just as much a right to lobby here as any steel corporation," he assured them that they had the "sympathy of the American people" and encouraged them to remain positive and refrain from any actions that might lose it.

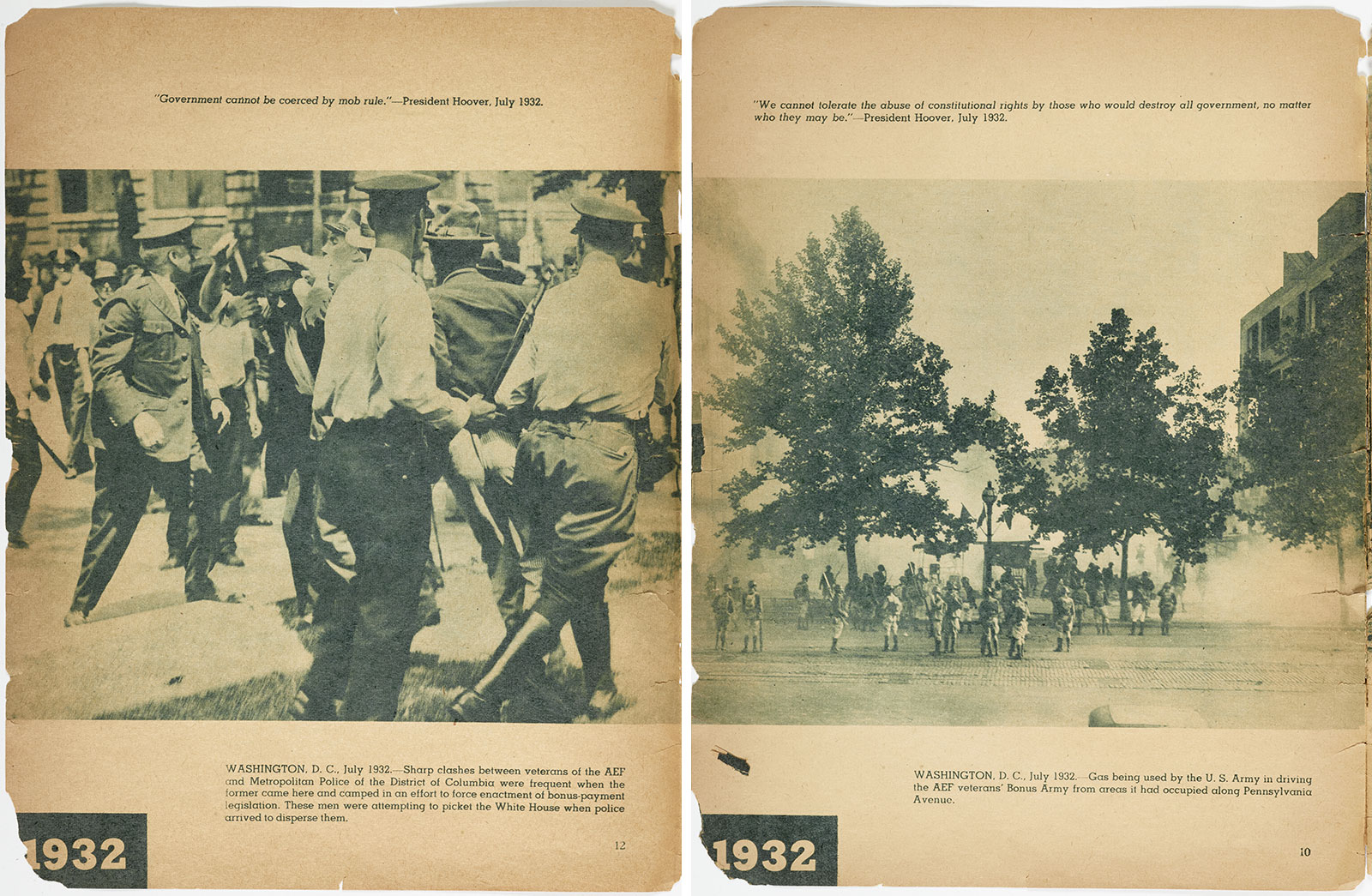

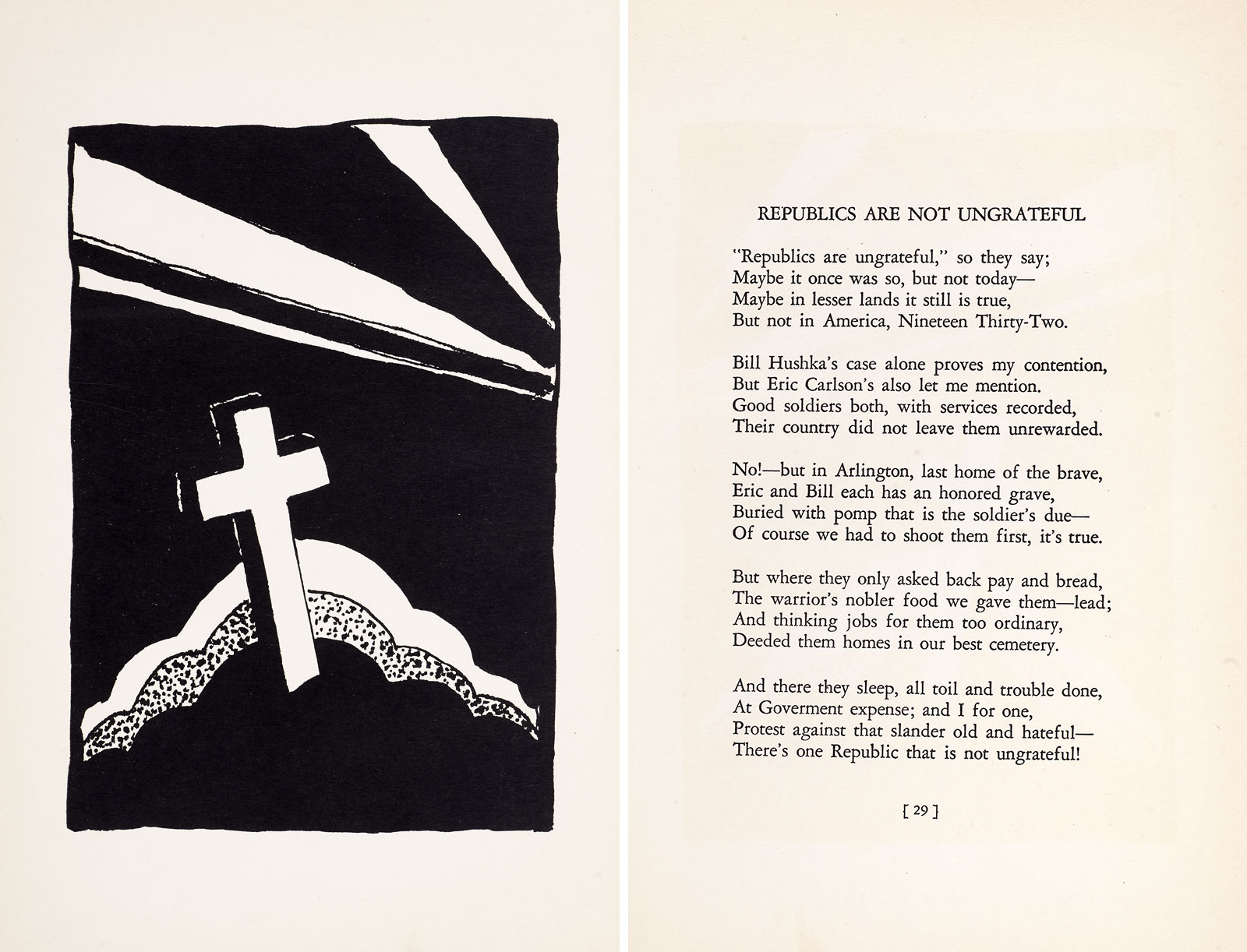

But following Congress's adjournment on July 16, President Hoover ordered the evacuation of the veterans from downtown Washington. As the police tried to forcibly evict veterans squatting in half-demolished buildings on July 28, bricks began to fly; two police officers shot into the crowds, leaving one veteran dead and another mortally wounded.

Hoover ordered General Douglas MacArthur and the Army to clear the city, deploying 200 saber-wielding cavalrymen and 400 infantrymen with bayoneted rifles, a force backed up by tanks and armored vehicles. After someone threw a stone, the troops donned gas masks and hurled smoke bombs and tear gas grenades, driving the choking veterans and their families from the streets. Numerous marchers were wounded, one malnourished 4-year-old died in the clash, and a 3-month-old child caught in the gas attack succumbed some days later.

Although Hoover told MacArthur not to advance on the veterans' camp across the Anacostia River, the general disregarded the president, crossed the bridge, and ordered his troops to burn down the shacks even as vets and their families rushed to salvage their meager belongings. According to one account, a soldier stabbed a boy in the leg as the child was trying to return to his burning shack to save his pet rabbit.

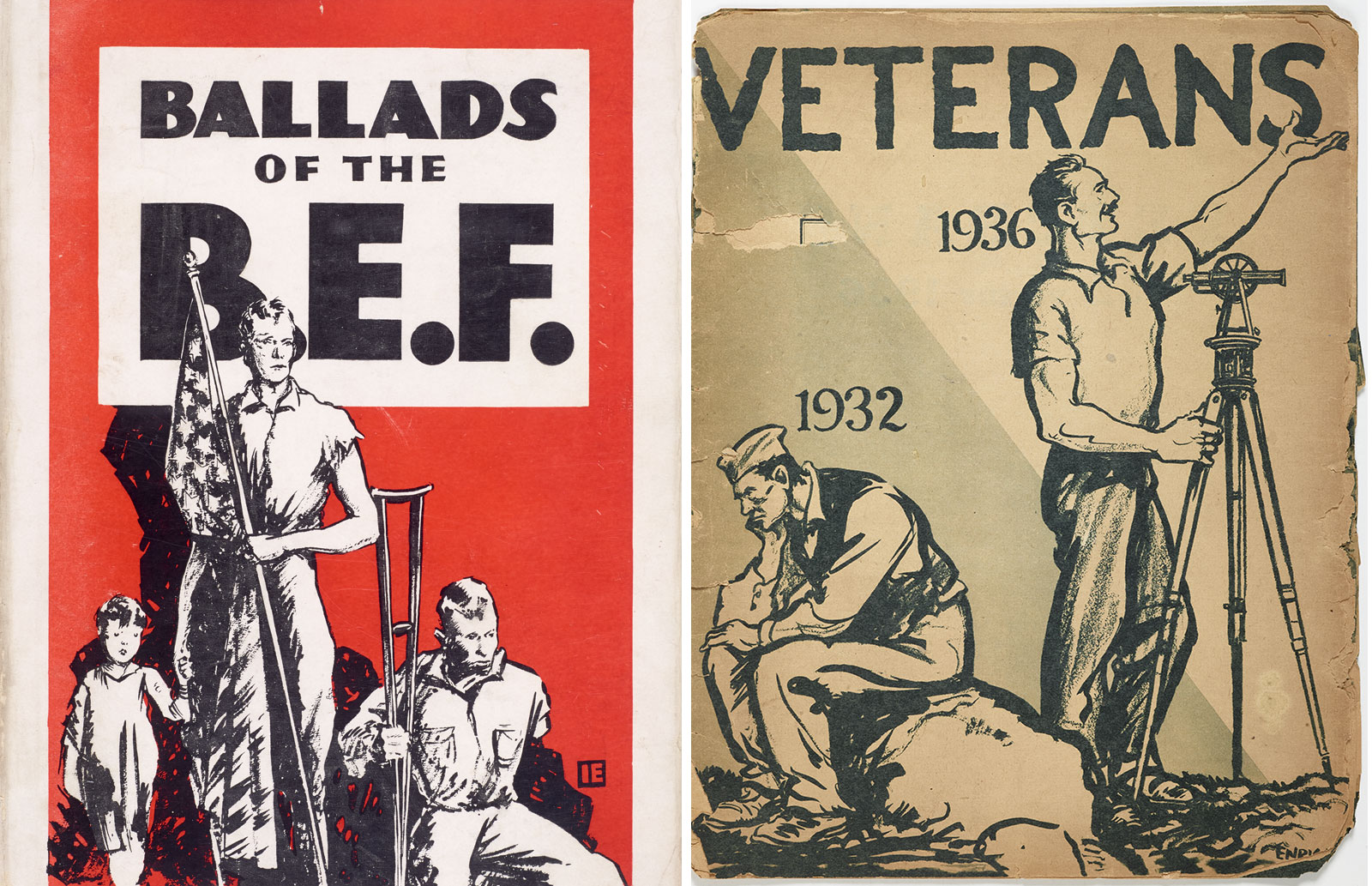

Newsreels showing the veterans' camp being razed shocked and horrified the American public. Attempting to justify the military action, President Hoover claimed without substantiating evidence that the remaining veterans had been manipulated and misled by Communist provocateurs intent on overthrowing the Republic. But the press and public rallied to the defense of the B.E.F. Upon learning of the firing on the Bonus Army encampment, General Butler officially declared himself a "Hoover-for-Ex-President Republican." The Washington Daily News also condemned the military action, editorializing that "if the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America."

The plight of the Bonus Army entered the American consciousness in two films released just before and after the 1932 presidential elections. The Washington Merry-Go-Round (1932) told the story of a newly elected representative who arrived in the capital city determined to smash the political machine that put him in office and to expose and turn out the corrupt politicos beholden to powerful lobbyists. Publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst also jumped on the Hollywood carousel, contributing much of the financial backing and editorial rewrites of another screenplay intended to turn Hoover out of office. In dramatic contrast to President Hoover's refusal to meet with Bonus Army leaders, the president in Hearst's film, Gabriel Over the White House, intercepts the veterans on their march on the capital, wades into the crowd against the advice of his Secret Service detail, and offers the vets jobs rather than handouts, promising to transform them from an "Army of the Unemployed" into an "Army of Construction." Hearst had hoped to produce the film in time to sway the voters in the 1932 presidential elections against Herbert Hoover and towards his own nominee, but the film was not released until the early months of 1933. The public did not need Hearst's prodding, however, as they overwhelmingly went to the polls and voted Hoover and his party out in a landslide election.