May 6, 2021

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

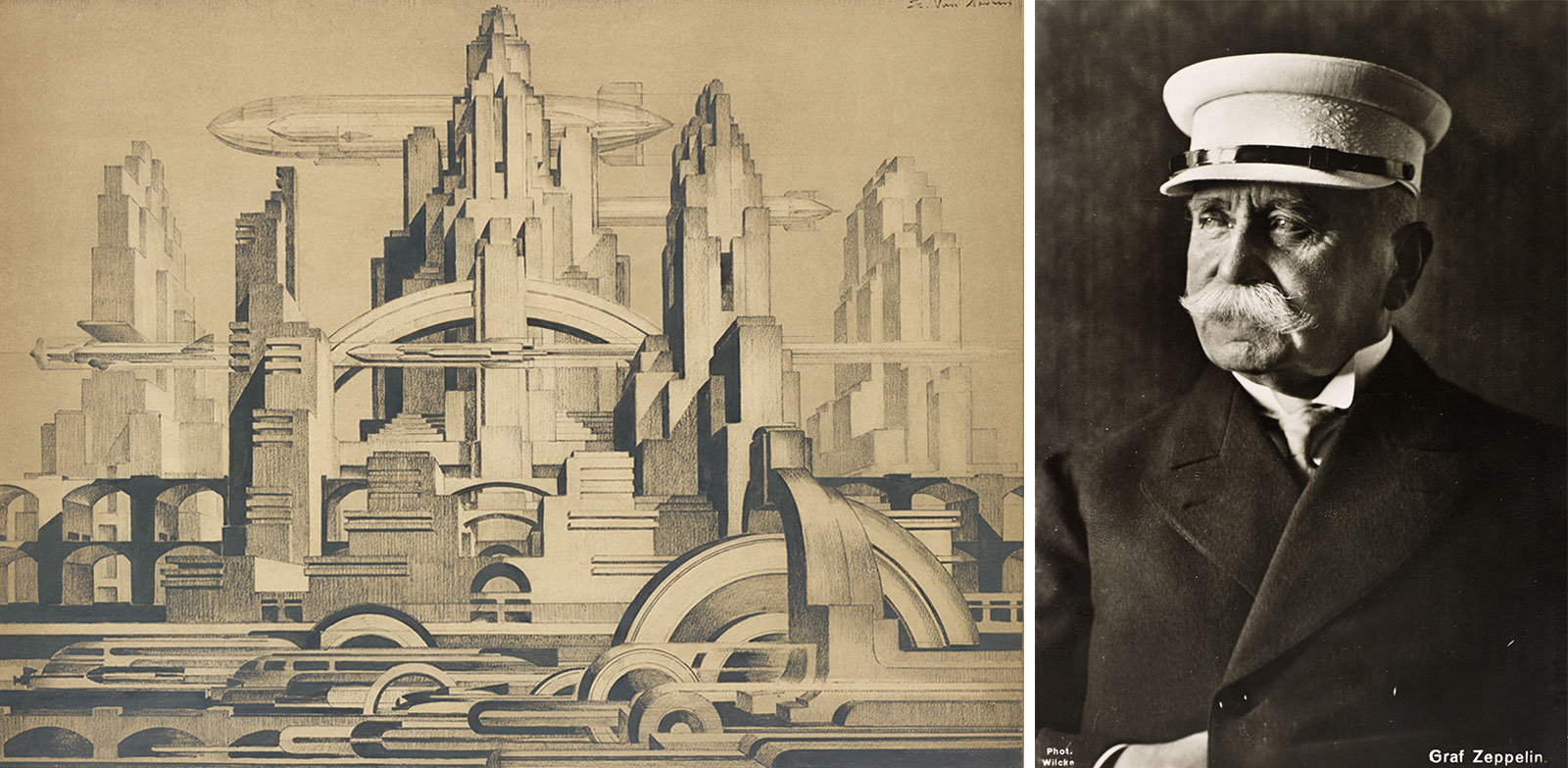

When most of us travel long distances, we almost invariably take flight as passengers in winged airplanes. But despite the ancient legend of Icarus and Leonardo da Vinci's inventive dreams of winged flying machines, the earliest aircraft that enabled human beings to ascend into the skies were balloons and their successors, zeppelins. Before the fiery crash of the LZ Hindenburg was captured by a radio announcer and film crews at Lakehurst, New Jersey, lighter-than-air zeppelins (rather than airplanes with their limited flight range) were expected to be the primary mode of the speedy, comfortable, safe, and luxurious long-distance air travel promised for the future.

Born in Konstanz, Baden (part of the German Confederation), in 1838, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin became fascinated by aerial flight. Having received a military commission in 1858, the count took a leave of absence in 1863 to travel to America and act as a military observer for the Union Army during the Civil War. He visited the balloon observation camp during the Peninsular Campaign and afterward traveled to St. Paul, Minnesota, met with the German-born balloonist John Steiner, made his first balloon-tethered ascensions, and became a lifelong advocate of lighter-than-air travel. Even as he rose in the ranks of German military command, Zeppelin remained obsessed with the possibilities of flight, expressing in his diary his ideas for large-scale airships as early as March 25, 1874. After Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs successfully created and tested their own non-rigid airship, La France, for the French Army a decade later, Zeppelin sent a letter to the King of Württemberg insisting on the military necessity of dirigibles and warning of the dangers of falling behind.

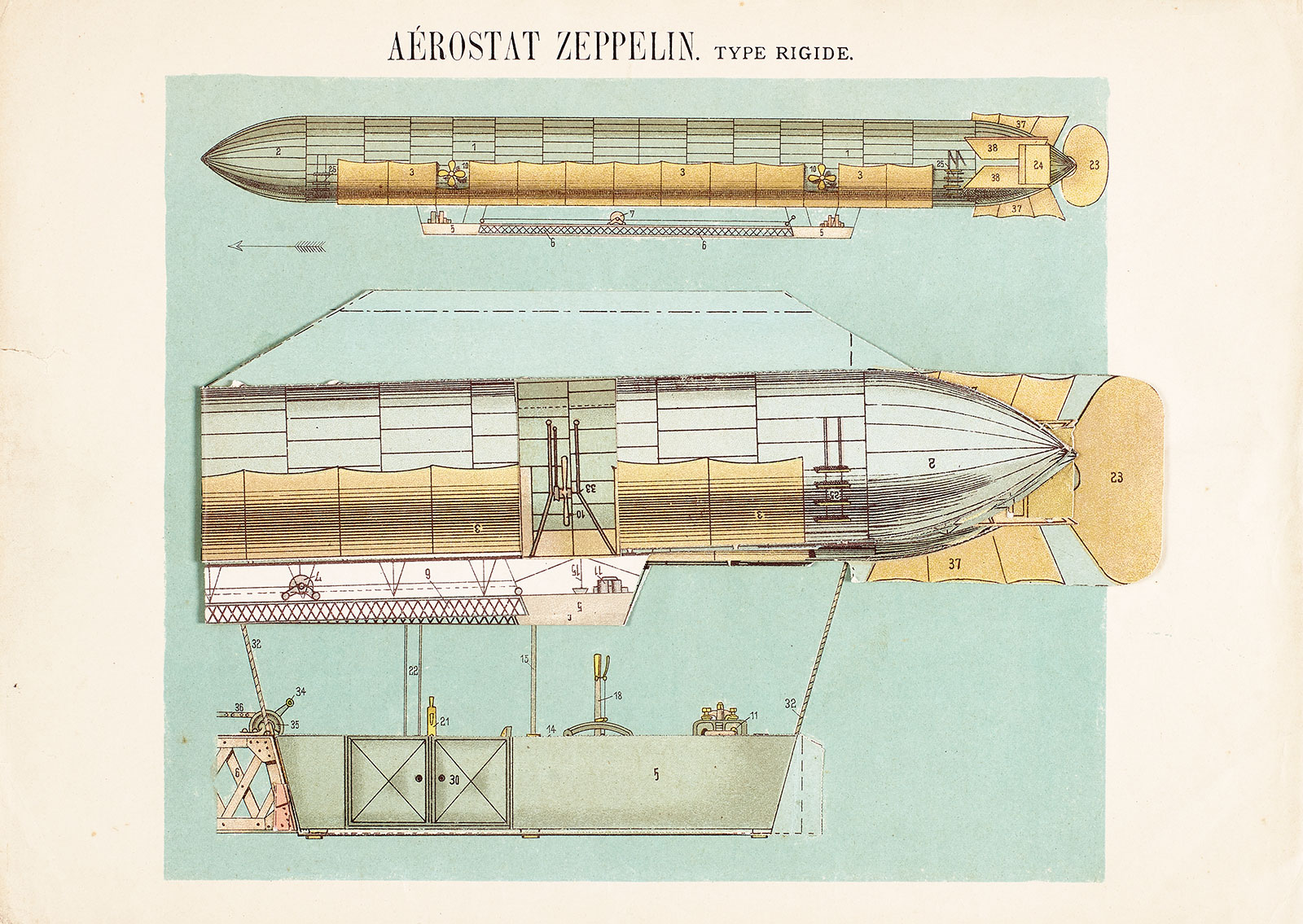

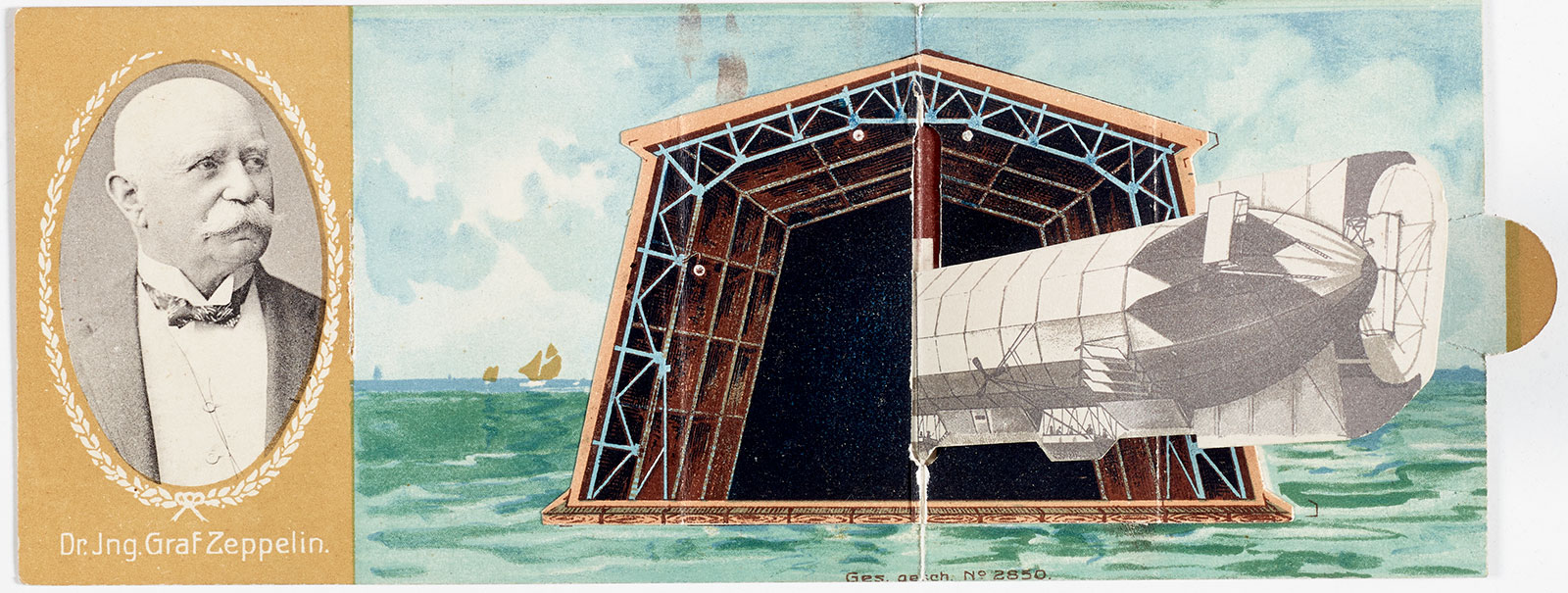

Resigning from the army in 1891, the 52-year-old count decided to devote the rest of his life and much of his family fortune to developing airships along the lines of his original idea: an exterior rigid duralumin envelope covered in fabric; a modular internal frame containing several cells filled with hydrogen gas; and external engines, a command control, and a gondola protruding from the underbelly.

Because of the spatial and airlift requirements for his airship, Zeppelin built a huge floating hanger on Lake Constance, tethering it by a single anchor to ensure the entrance was always lined up with the wind. Zeppelin's first airship, the LZ 1, ascended into the air and hovered over Lake Constance for 20 minutes on July 2, 1900—nearly 3 1/2 years before the Wright brothers made their groundbreaking flights in a powered, winged airplane. Larger and more refined models of the first zeppelin soon followed, and in October and November 1908, successful test flights of the LZ 3 that included the Kaiser’s brother and crown prince as passengers convinced the German government to award Zeppelin the Order of the Black Eagle and to commission the refined L II design for military service.

Even before the outbreak of the First World War, Zeppelin's military contract kept his airship company afloat, while the business manager of the Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin firm capitalized on the popularity of the airships by establishing a civil and commercial passenger service. As many as 37,250 passengers embarked on more than 1,600 flights aboard airships before 1914 without a single incident or accident, dominating the skies and delivering the promise of fast and comfortable travel through the air.

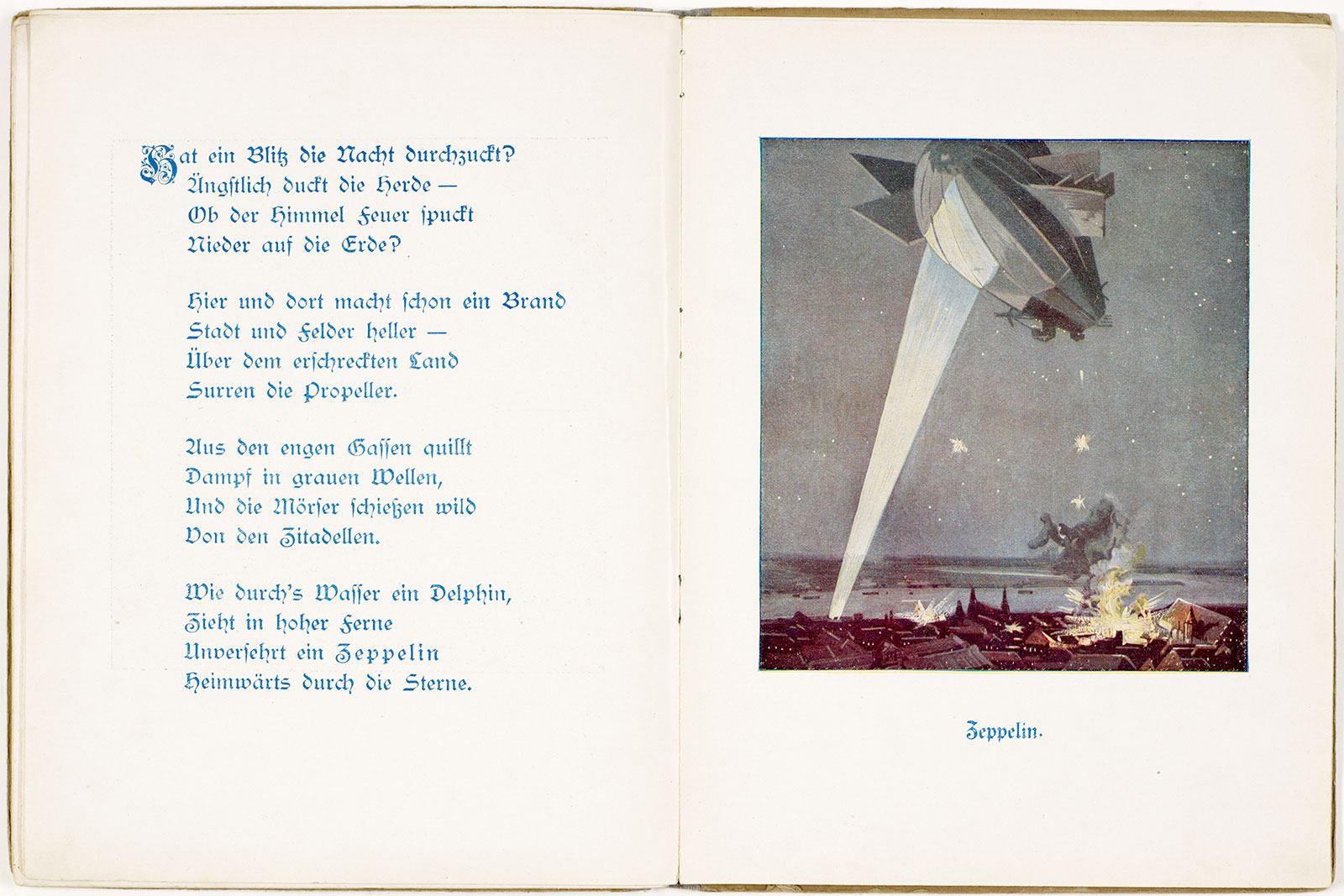

At the start of the First World War, the German Army deployed its several zeppelins on reconnaissance missions. But as the Western Front's trench warfare created a stalemate, the German military command used the aerial juggernauts to strike fear in the enemy, leveraging the zeppelins' ability to travel at speeds of 85 miles per hour, easily cross the Channel, and drop bombs on English towns and cities. The zeppelins' reign of terror killed a total of 500 civilians and injured over 1000 more before the British met the zeppelin threat by exploiting the airships' vulnerability, firing explosive bullets into the behemoths filled with flammable hydrogen gas. The Germans discontinued the zeppelin raids in 1917—the same year that Zeppelin died, after 77 of the 115 military airships had been downed, destroyed, or disabled—and in the following year the Royal Air Force was formed to engage the German heavy bomber airplanes supplanting airships. After the war, the Treaty of Versailles forced a provisional cessation of the zeppelin program.

After the war, Dr. Hugo Eckener assumed control of Zeppelin's airship company. Although limited from building large airships, Eckener persuaded the American government to permit him to build the LZ 126 for delivery to the U.S. Navy as part of German reparations. Eckener captained and delivered the airship (rechristened the USS Los Angeles) to Lakehurst, where it remained the Navy's longest-operating rigid airship and was memorialized in such decorative arts objects as a hanging lamp.

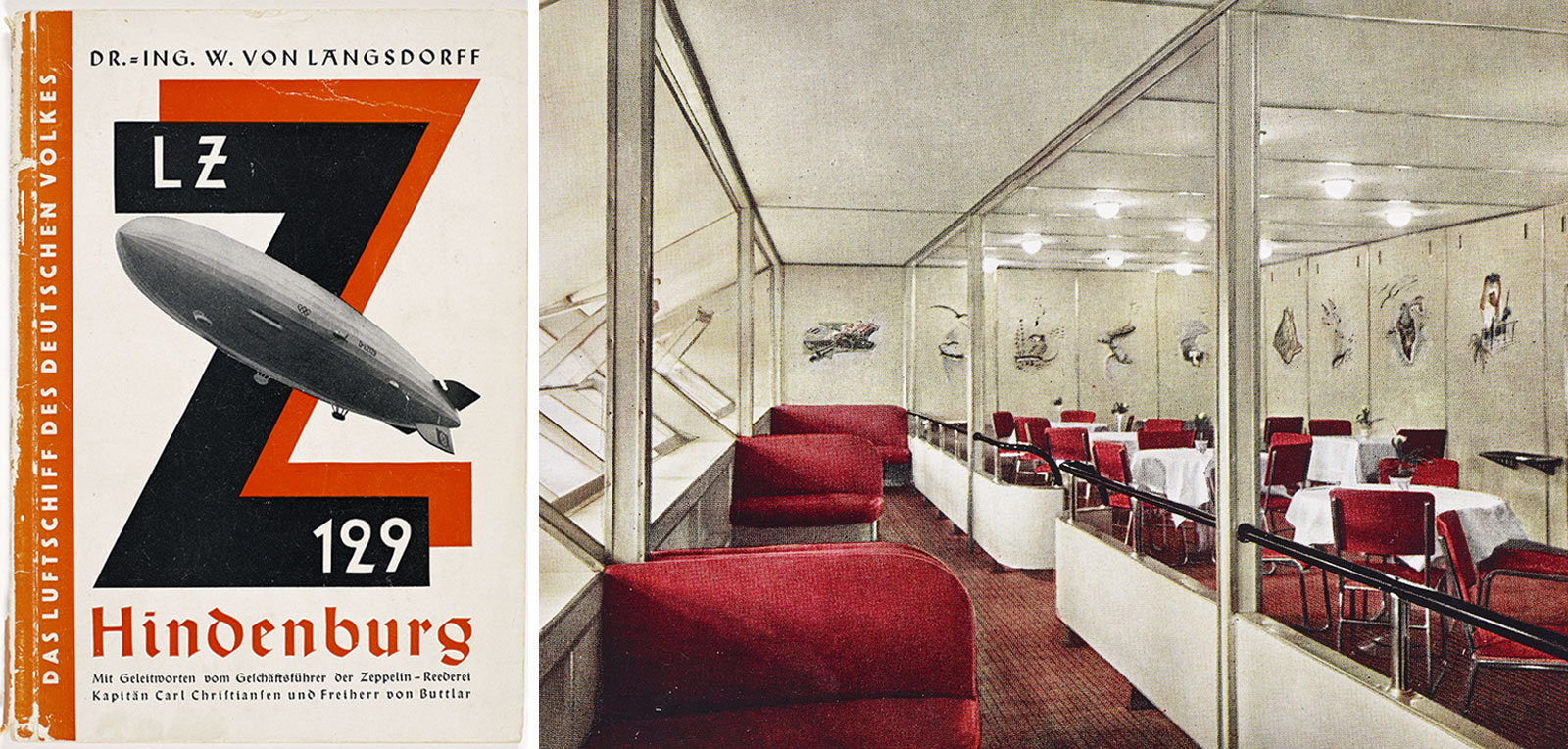

As postwar Germany's Weimar government lacked the funds to revive the zeppelin, Eckener promoted the construction of the LZ 127 with a national lecture tour. Eckener's dream of creating a luxury airliner came to fruition and the great airship was christened the Graf Zeppelin. Eckener captained the airship on its first flight to the United States and all of its record-setting flights: the 1928 intercontinental passenger flight, an around-the-world flight in 1929, and a flight to the Arctic in 1931. Because of Eckener's insistence on "safety first," not a single passenger sustained a serious injury over the course of more than a million flight miles.

Eckener became so popular a figure in Germany and so outspoken a critic of the National Socialists that after Adolf Hitler took power in 1933, the Nazis nationalized the zeppelin industry and minimized Eckener's influence by appointing party loyalists as managing directors and air pilots. In 1936, the Nazis completed construction and testing on the LZ 129 Hindenburg, the largest hydrogen-filled airship ever entered into service.

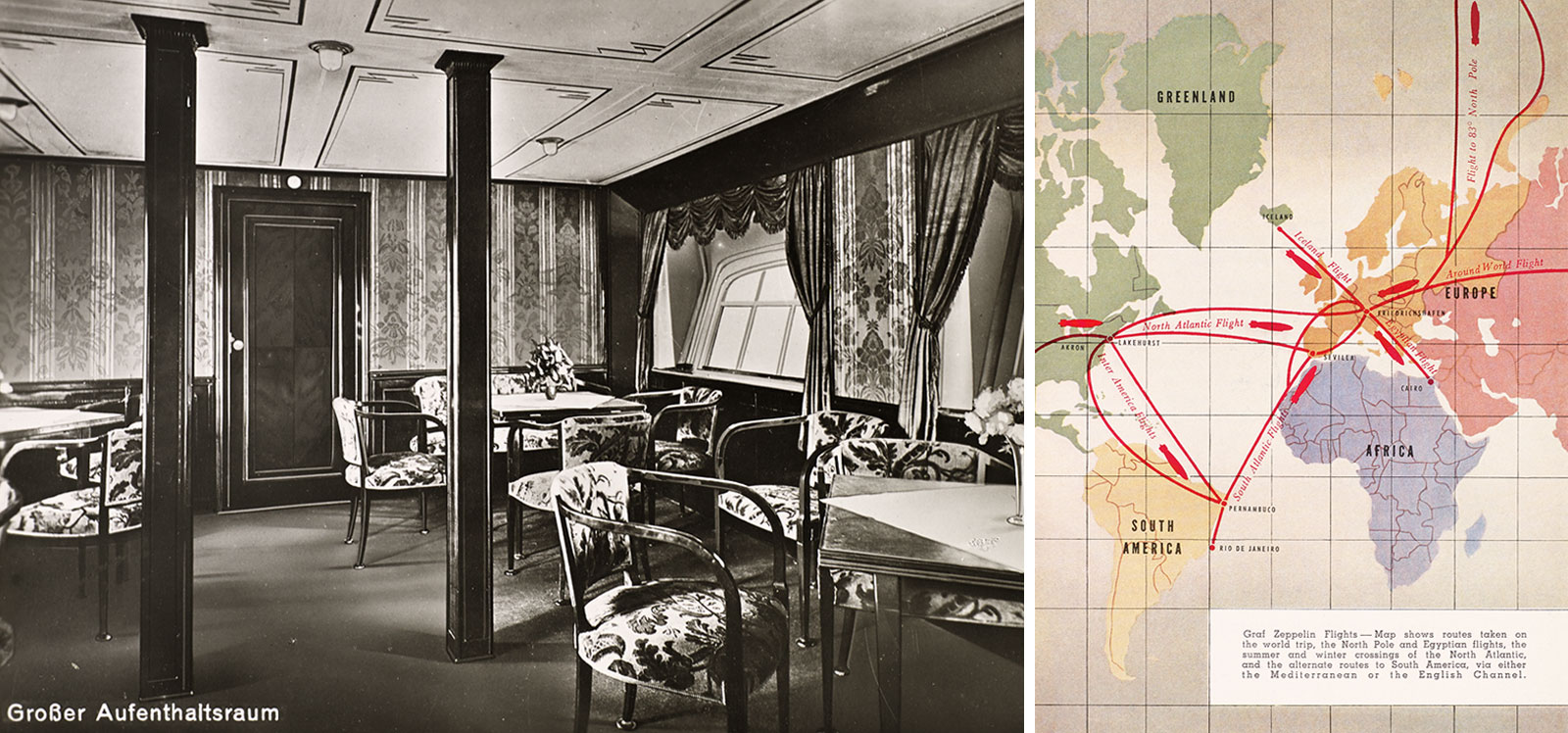

After 62 trial and publicity flights, the 13-story tall, ocean liner-sized zeppelin made 20 successful crossings of the Atlantic in a single year. Designed for commercial service, the Hindenburg offered its passengers all the comforts one might expect aboard a luxury liner, including private staterooms, a dining area, reading room, and a bar and lounge equipped with lightweight but comfortable tubular aluminum furniture.

While the costs of travel by airship excluded all but the very wealthy, this was also true of air travel generally at the time. The zeppelin afforded its passengers the ability to walk freely about the gondola and enjoy spectacular views; by contrast, even the most luxurious airplanes of the period confined passengers to cramped seating arrangements and a bumpy ride as small craft were buffeted by the winds.

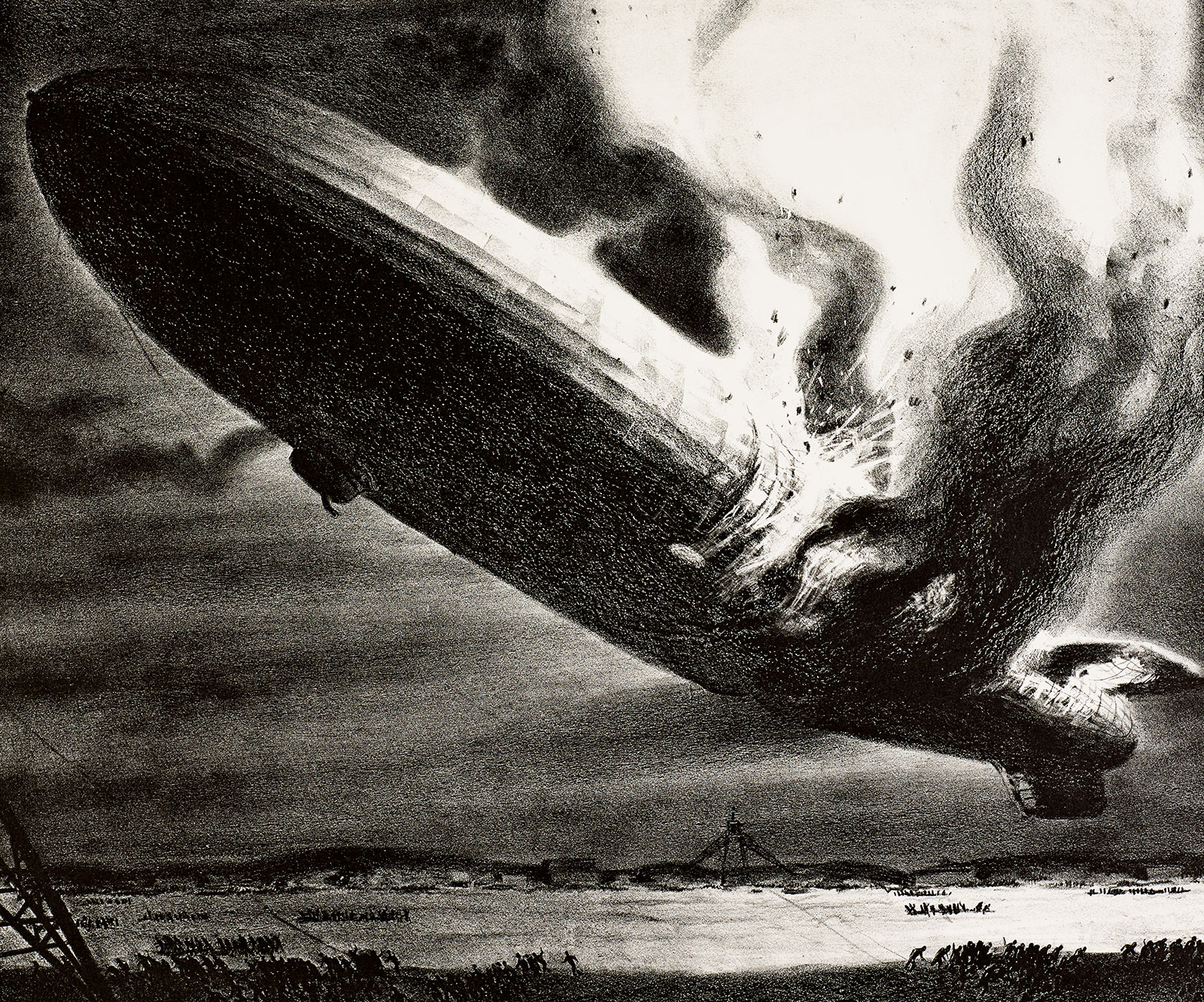

Although airship pilots doubled as expert meteorologists to ensure fast, safe, and comfortable passage, the fact that the zeppelins were filled with highly flammable hydrogen gas made them extremely vulnerable to sparks or lightning storms. On May 6, 1937, as Hindenburg was still 60 meters above the ground and attempting to land at its mooring mast at Lakehurst, a presumed leak in one of the airship's gas bags ignited, and within 34 seconds each of the hydrogen-filled gas bags inside burst into flames until the giant canvas-covered structure was consumed in a fiery crash.

Of the 97 people aboard, 29 died at the crash site and another 6 succumbed to their injuries at the hospital. A young radio announcer, Herbert Morrison, had been on hand with a film crew there to capture the landing. The fiery Hindenburg tragedy was neither the first nor the deadliest airship disaster, with 62 persons surviving, but the verbal and visual record of the event ensured worldwide exposure and negative publicity.

While Eckener oversaw the building and commission of the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II in 1938–39 and hoped to substitute noncombustible helium gas for hydrogen, the United States remained the sole source of substantial helium reserves and refused to allow shipment to the Nazi regime. Consequently, Eckener refused to put the Graf Zeppelin II into service as a commercial passenger ship and Air Marshall Hermann Goering decided to scrap the ship and its hangars to provide material for building military planes after the start of the Second World War. Only in the last few years has the idea of reviving airships been floated as more ecologically sustainable means of transporting goods and people to otherwise inaccessible places on the planet.