May 1, 2021

Donald Vogel's Subway Maypole

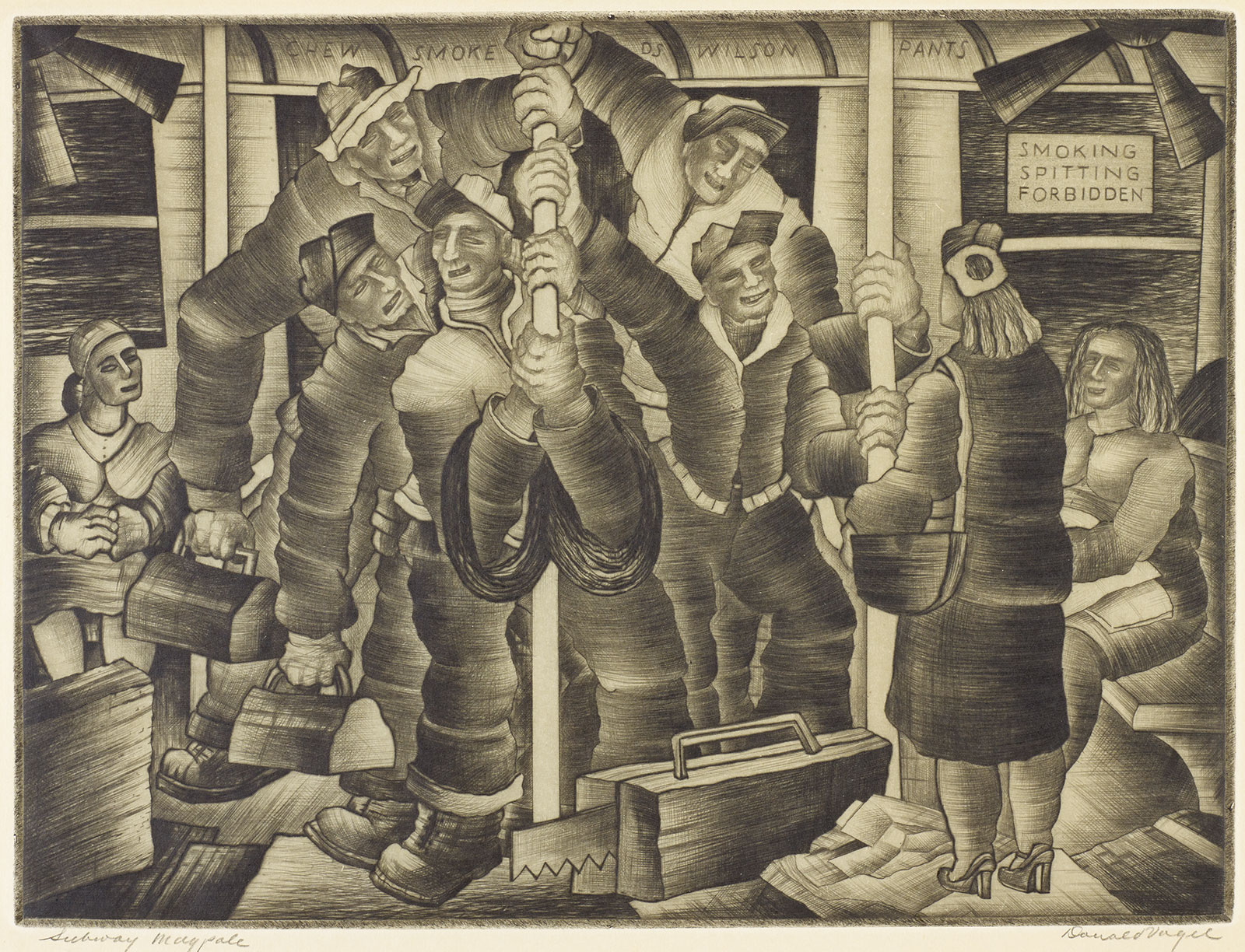

Print, Subway Maypole, c. 1940

Donald Vogel (American, b. Poland, 1902–1986)

New York City

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, TD1989.87.3

Dark, somber, and cramped, Donald Vogel's Subway Maypole is a far cry from the colorful, idyllic countryside maypole dancing that many of us associate with the first of May. May Day stems from an ancient festival that featured dancing, singing, and cake in celebration of the start of spring, however in 1889, May 1 also became associated with the idea of work when socialist and labor parties refashioned the public holiday as International Workers' Day to commemorate the 1886 bombing at Haymarket Square in Chicago. This deadly event—which began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour workday—led to May Day's recasting as Labour Day (not to be confused with September's Labor Day in the U.S.), with parades by trade unions and labor associations.

Subway Maypole, produced around 1940, speaks to so many issues contemporary to the artist's time: urban life and transportation, increased crowding in cities, a growing sense of disillusionment, even the largely male labor force. Vogel—who was born in Poland in 1902, emigrated to the U.S. at age eight, and studied at the Parsons School of Design and Columbia University—frequently focused on city life in his work and, as with other post-Depression era artists like Miriam Tindall Smith and Daniel Ralph Celentano, reflected an interest in social realism by spotlighting the socio-political conditions of the working class.

Though usually more literal in his gritty life depictions, Vogel takes a more philosophical approach with Subway Maypole, reimagining a rural scene for a city setting. The celebratory agrarian maypole, often depicted surrounded by young women and girls, is now merely a functional urban maypole for grimacing, mostly male workers, tools in hand. The no spitting/smoking sign just above them makes perfect sense in the confined spaces of municipal transportation and echoes an 1896 ordinance that made spitting illegal in New York public areas after bacteriologist Robert Koch linked the spread of tuberculosis—like so many other diseases—to spittle. Vogel's perspective meshes the centerpiece of traditional May Day with the spirt of modern Labour Day, and though not intentional, perfectly encapsulates the shift from agrarian to industrial economies that fueled many of the machine-age works featured in the Wolfsonian collection.

– Marlene Tosca, art director