March 11, 2021 (updated March 18, 2021)

By Jon Mogul, Associate Director of Research, Education + Grants

You may not know Lucienne Bloch's name, but if you're the kind of person who reads museum blogs then there's a pretty good chance you know her work. As a young artist, just returned to the United States from several years studying and working in Europe, Bloch happened to be seated next to Diego Rivera at a dinner in New York City in 1931. The two struck up a conversation, and Bloch ended up working as Rivera's assistant. She became close friends with him and, especially, Frida Kahlo, and it was Bloch's Leica camera that captured many iconic photographs of Kahlo over the next year or two.

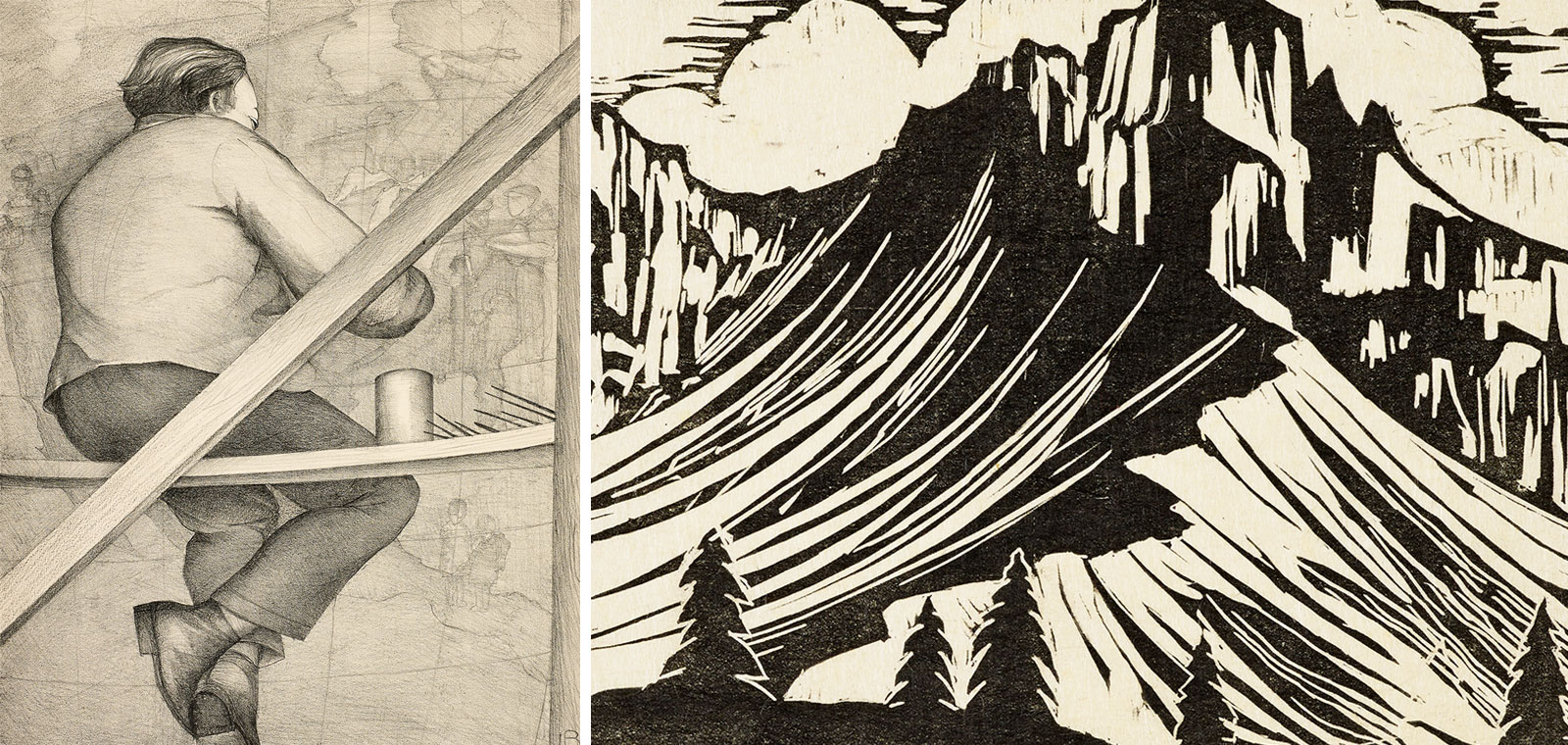

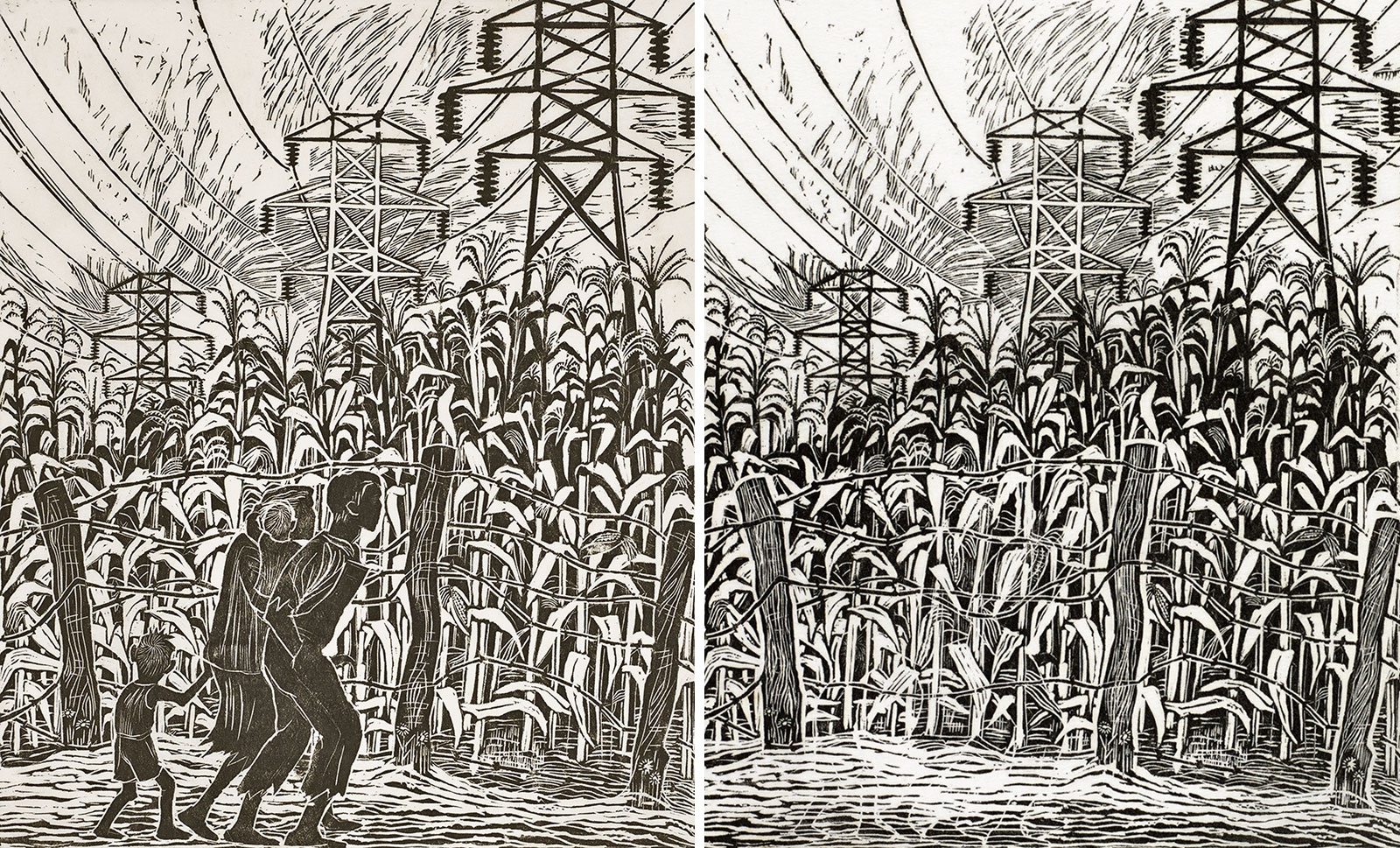

But Bloch's career was much bigger than her association with the two legendary Mexican painters. She also made woodcuts and lithographs, several of which are represented in The Wolfsonian's collection. They show a range of interests and influences. Probably her best-known among these is a woodcut called Land of Plenty—a piece of Depression-era social commentary about rural economic inequality in the United States. Intriguingly, after printing one edition showing a family in front of the barbed wire fence, she modified the block to remove the family and produced a second edition, two years later, without human figures. An inscription that she later added at the bottom of the print in our collection reads: "After I printed 30 with the figures, I printed 10 more removing the figures because it seemed more subtle to have just the fence! At the bottom one can see vaguely the footsteps!"

Bloch was accomplished in other artistic fields as well. She designed glass sculptures for the Leerdam Glass Factory in the Netherlands. These works caught the eye of Frank Lloyd Wright, who invited her to teach at Taliesin East—an offer that she seems to have considered but did not accept. She also illustrated children's books. And, beginning with her work for Rivera, she became a prolific muralist, whose works graced the walls of schools, businesses, places of worship—and a penal institution, the Women's House of Detention, in New York City's Greenwich Village.

The Women's House of Detention served both as a pre-trial detention center and as a prison for women convicted of offenses. An Art Deco building designed by the firm Sloan & Robertson and completed in 1932, it replaced the notoriously overcrowded and unsanitary Jefferson Market Prison at the corner of Greenwich Avenue and West 10th Street. It was meant to embody the relatively new ideal of prisons as places of social reform, rather than punishment. The prison's director was quoted as saying:

"A major portion of the women who will be confined . . . represents social problems. It is our task to help them in readjusting to society's demands. Aside from their distressing need of physical rehabilitation, we hope to contribute towards their moral and social rehabilitation, proving that a prison can be a place for restoration as well as for punishment."

Bloch got a commission to paint a mural in the 12th-floor recreation room through the Federal Arts Project (FAP), a New Deal agency that offered work to struggling artists. She wanted not only to brighten the room, but—in the spirit of rehabilitation—to provide encouragement to the confined women by showing them a picture of what their lives might be like after their release. The plan was to create frescoes for three walls of the room, collectively titled The Cycle of a Woman's Life. She managed to complete only one wall, a scene of women and children enjoying themselves on a New York playground.

As a newspaper article from the time makes clear, the House of Detention—whatever its aspirations to social reform—practiced segregation, and the 12th-floor recreation room was meant for Black inmates. In planning the project, Bloch, a white artist, visited the prison and spoke with both staff and the incarcerated women. She recounts that she showed a group of the latter a print she had made several years earlier in Detroit depicting a group of Black youth on a playground. While they liked the theme of women and children, they also requested that she paint a scene of racial integration—and Bloch complied. Her mural advanced what was, for its time, a progressive vision of race relations (it calls to mind a famous passage in Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech).

Since Bloch did not get a chance to add her frescoes to the two side walls, it's not certain exactly how she planned to picture the "cycle of a woman's life." There are some clues though. Bloch was one of the artists included in Vassar College Art Museum's 1976 exhibition 7 American Women: The Depression Decade. That show's catalogue lists (sadly, without illustrations) three sketches on tracing paper that she made in preparation for the mural. They are titled: School, Childhood, Family; School, Work; and Playground, Family.

This House of Detention project was just the second mural that Bloch completed, and it made her a minor art world celebrity. The project got a lot of positive press (including a long write-up in The New York Times) and earned her a place in Vanity Fair's "Hall of Fame" for 1935. It launched her as a sought-after muralist, leading to another FAP commission in the 1930s, for George Washington High School in upper Manhattan. Among her many postwar projects were a mural for Temple Emanuel in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and an abstract mosaic for the façade of a San Jose IBM building—one of the first structures in what became Silicon Valley.

The House of Detention, demolished in 1973, is long gone, but it had its own fascinating history (the subject of a forthcoming book by historian Hugh Ryan). The roster of inmates is practically a "who's who" of politically radical and/or socially non-conformist women: Ethel Rosenburg, Dorothy Day, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Andrea Dworkin, Angela Davis, Afeni Shakur, and Andy Warhol's would-be assassin, Valerie Solana. Because it was the landing place for women who were arrested during NYPD sweeps of lesbian bars, it became a center for queer life in Greenwich Village and a target for gay rights protests. It was also notorious for unsanitary conditions and abusive treatment of prisoners, as detailed in newspaper exposés as well as a 1970 interview given by Angela Davis. The city shut it down in 1971 and transferred prisoners to a new facility on Rikers Island. When they arrived, they would have seen a newly commissioned mural by Faith Ringgold that reflected an updated vision of women's roles (a vision that I suspect Bloch would have embraced).

An earlier version of this post included two watercolor studies from The Wolfsonian's collection previously attributed to Lucienne Bloch. We have since learned that these works were probably not made by Bloch, and likewise not related to the House of Detention mural.