February 19, 2021

Citizen 13660, by Miné Okubo

Book, Citizen 13660, 1947 (first printing 1946)

Miné Okubo (American, 1912–2001), author and illustrator

Columbia University Press, New York City, publisher

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, 83.2.740

February 19 is the anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066, which ordered the evacuation of people "deemed a threat to national security" to relocation centers away from the West Coast. The order led to the internment of around 120,000 Japanese Americans, the majority of them American citizens, in concentration camps spread out across the western United States.

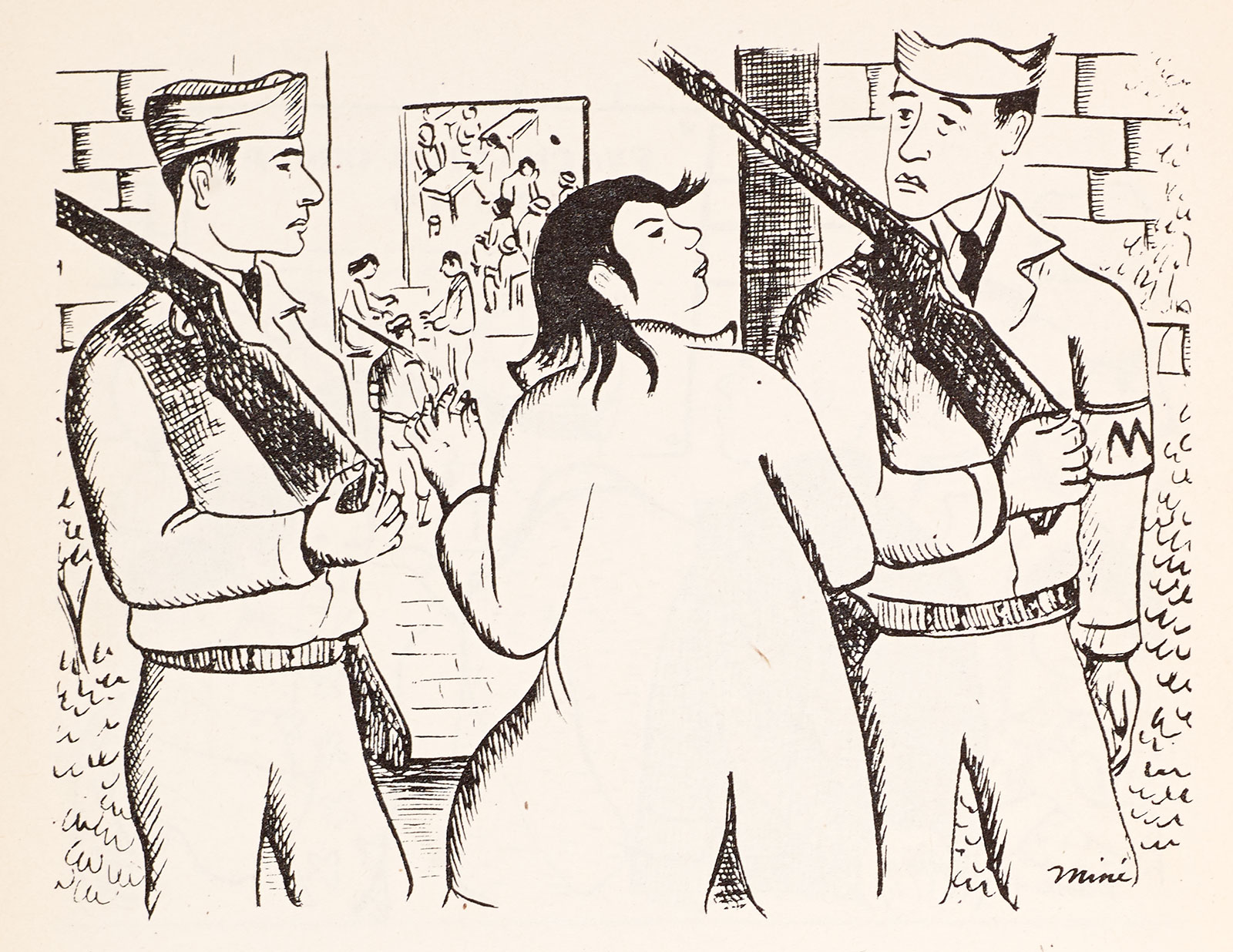

Japanese-American artist Miné Okubo wrote and illustrated Citizen 13660 in 1946, making it the first published account of life in Japanese internment camps during the Second World War. Decades later, it remains a vital historical record and a remarkable work of art. Early in her career, Okubo studied under Fernand Leger in Europe, worked with Diego Rivera on the epic mural Pan-American Unity for the 1939 San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition, and created her own murals and mosaics for federal buildings as part of the New Deal. In 1942, however, she and her family were forced to evacuate their homes and report for internment—first to Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, and then to Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. Okubo would later remark on the irony of producing artwork for the U.S. government one day and finding herself its prisoner the next.

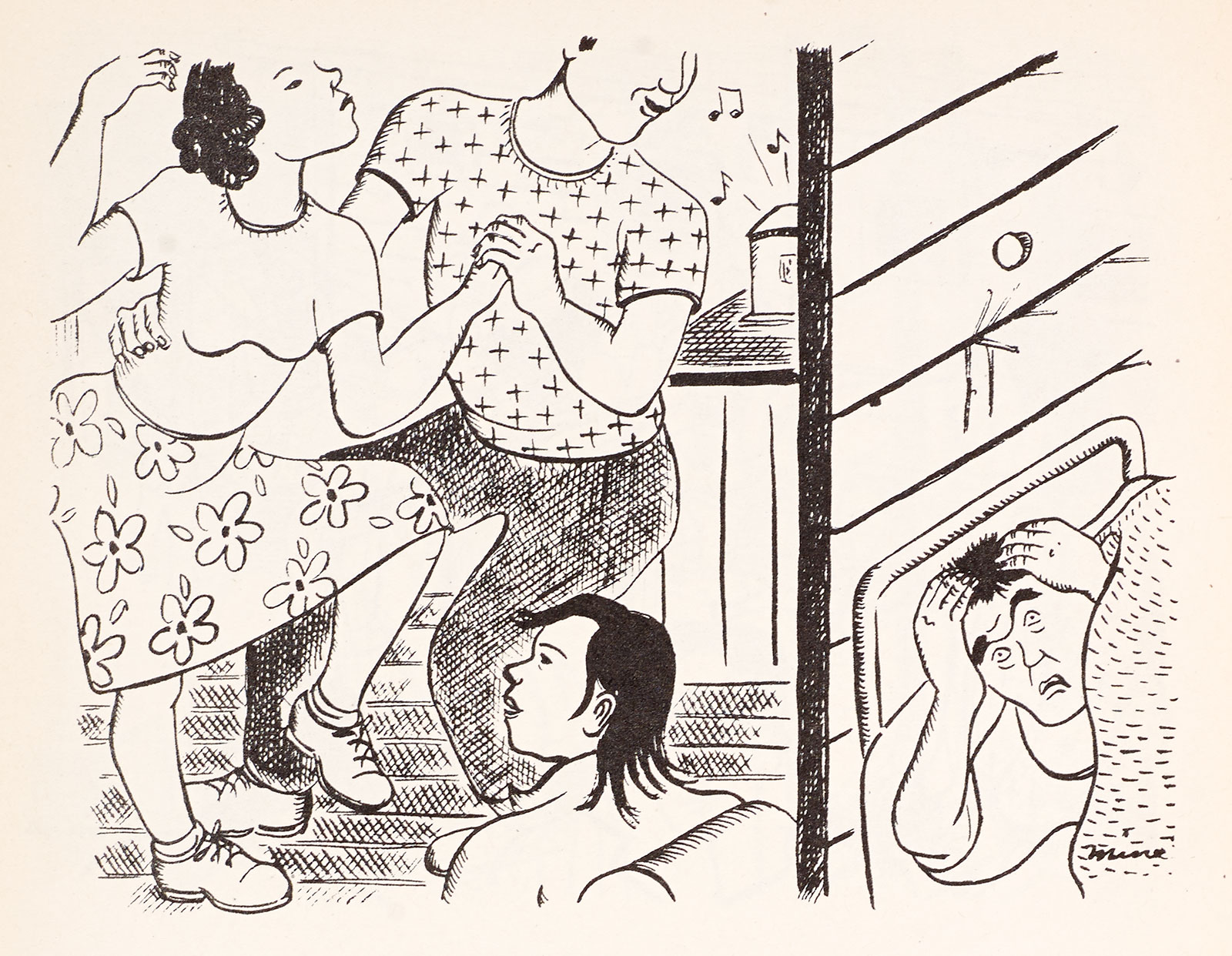

Citizen 13660 takes its name from the number assigned to Okubo and her brother when they entered into the concentration camp system. She began documenting her experience through drawings almost immediately, capturing both everyday life and her own internal thought process. Okubo's style is straightforward, even simple, letting the personalities of her fellow inmates shine through, and her lines are weighty, imparting both humor and frustration in a single scene. On page 66, for instance, she describes the camp's crowded living quarters, showing how residents could not avoid becoming embroiled in each other's troubles, small victories, and late-night jitterbugs. Her use of black and white began as a necessity—based on what she had regular access to in the camps—but it was also an aesthetic decision. Later, she explained, "I like solid things… if you use color, you might end up being pretty."

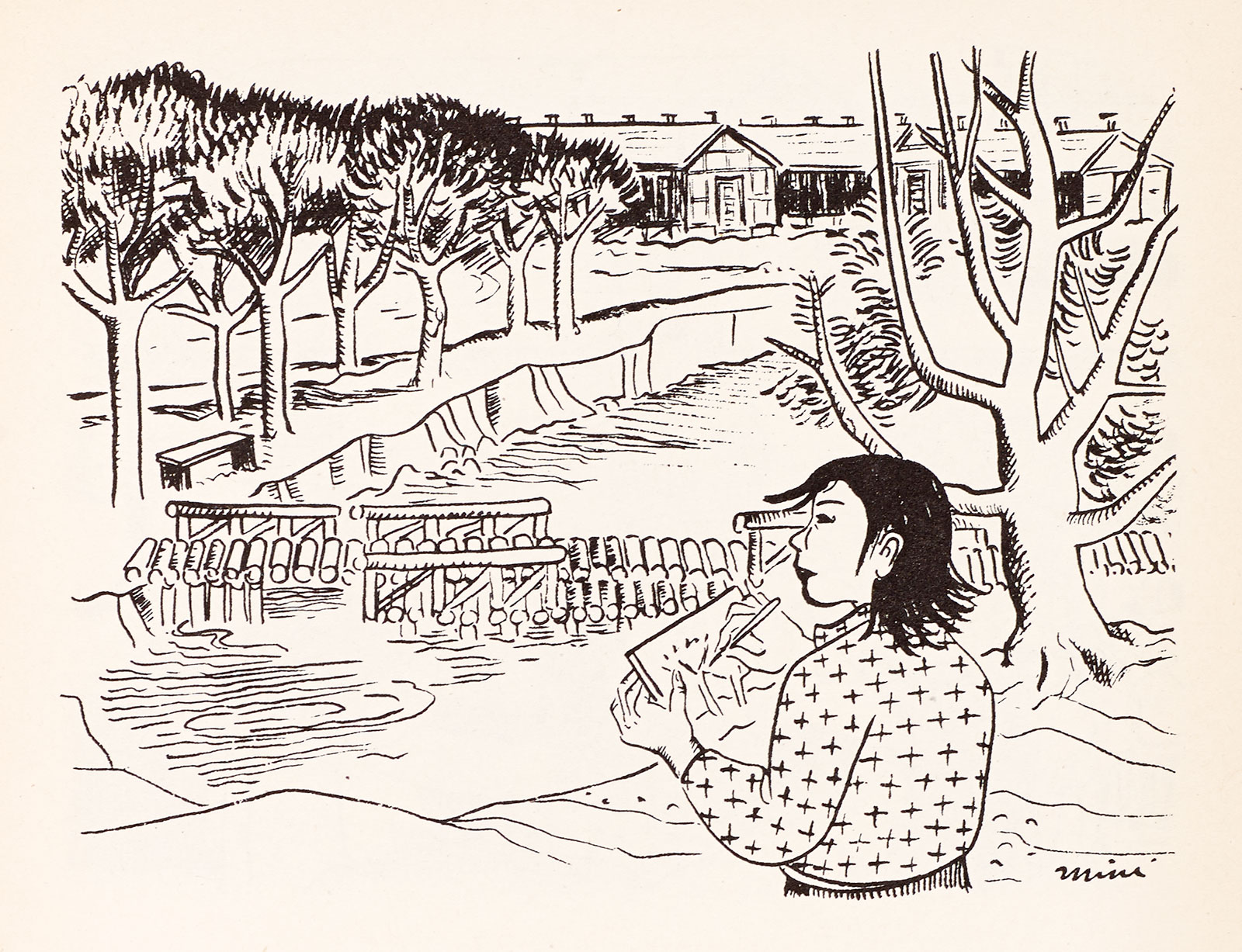

While Okubo documents the indignities of life in the camps, she also captures moments of joy and solidarity. On page 99, for instance, she tells the story of a group of landscape architects who, needing something to do while forcibly removed from their everyday lives, transformed a desolate corner of the camp into a verdant landscape and lake. That balance—the bitter irony of memorializing slain Japanese-American soldiers against the delight of an evening dance party in the barracks—was perhaps carefully calibrated to avoid having the book blacklisted for its criticism of internment, but it also helps the reader see Okubo and her fellow camp inmates as fully realized individuals rather than nameless victims of a cruel government system.

Okubo earned a work release from Topaz in 1945 and moved to New York, where she worked as a commercial illustrator and practicing artist for decades. Citizen 13660 remains the work for which she is most famous, but her art can be found in museum collections across the country.

– Shoshana Resnikoff, curator