February 4, 2021

Spurred by 2020's Black Lives Matter protests, cultural organizations are taking a hard look within as centuries-old practices and attitudes are examined with critical eyes. More respect, better representation, improved access, and richer storytelling have been a long time coming in the museum field, and now many institutions share a keen interest in reshaping the system from the ground up.

Our founder, Micky Wolfson, believes that the collection is a window into the modern age—each object, a mirror of its maker and culture. This approach is core to our museum and mission, and in this spirit, we preserve and acquire works that provide a three-dimensional understanding of humanity. Though The Wolfsonian has reached beyond the expected since the beginning, studying materials many others have discarded or forgotten, today we must push even further to ensure our holdings contain more than the stories written by history’s privileged. We're considering the contributions of women; the experiences of those who lived under the yoke of colonialism rather than simply those who profited from it; and the agency, achievement, pride, and daily life in communities of color, to list just a few facets of our thinking.

The Wolfsonian can and will bring 21st-century values to bear on the historical events and conditions of our past. The following items are a tiny fraction of our collection's material relating to marginalized groups; some are recent gifts and purchases, while others are old standbys. Here, our team shares their takes on these selections, all examples of a fresh direction and renewed interest in areas of the collection to be more deeply explored.

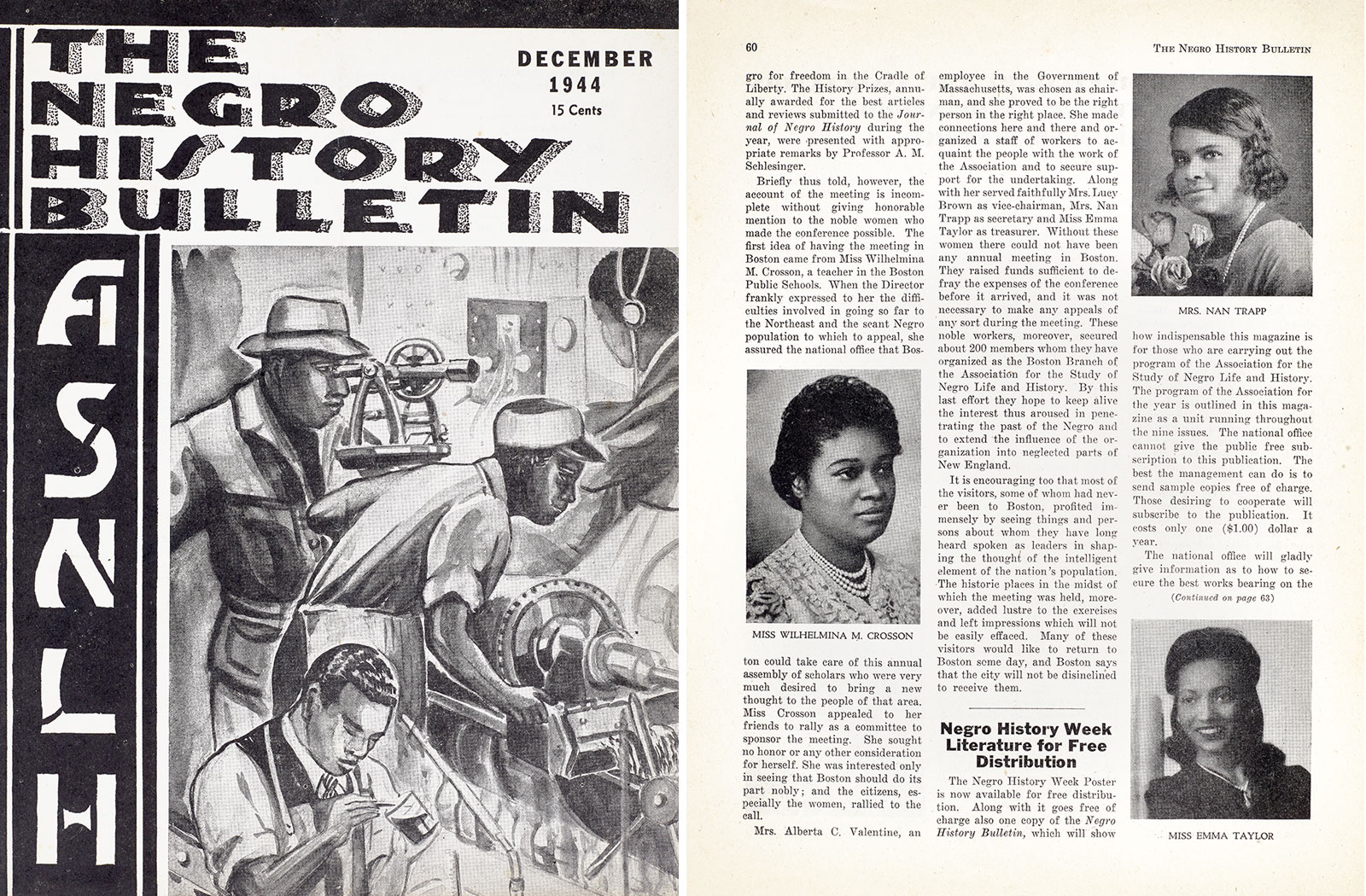

The Negro History Bulletin

The Negro History Bulletin, known today as the Black History Bulletin, has been published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) since 1937. ASALH was established in 1915 by Dr. Carter G. Woodson with a mission to create and disseminate knowledge about Black life, history, and culture. Woodson, the son of former slaves, firmly believed in the importance of education for securing and making the most out of one's right to freedom. In 1912, Woodson became the second African American to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard University, and to combat the lack of information on the accomplishments of Black people, he founded ASALH soon after.

ASALH's first periodical was the Journal of Negro History, a research and publication outlet for Black scholars. At the request of ASALH board member Mary Jane McLeod Bethune—founder of Bethune-Cookman College, advisor to President Theodore Roosevelt, and later vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP)—Woodson and ASALH began publishing the Bulletin as both a resource for educators and as an easier read for the general public than the high-level writing of the Journal. With several women on the editorial board and increasing numbers of article contributions written by women teaching in public schools, the Bulletin quickly became a largely women-led operation. The pages of the Bulletin include historical overviews, book reviews, contemporary accomplishments, and a children's section to foster an appreciation of history in all ages.

Along with The Crisis, published by the NAACP, The Negro History Bulletin is an important example of Black publishing in The Wolfsonian Library. Future collecting goals include expanding our holdings of Black publications to tell a fuller story of the rich history of African-American publishing in this country.

– Erin Heffron, Library Collections Specialist

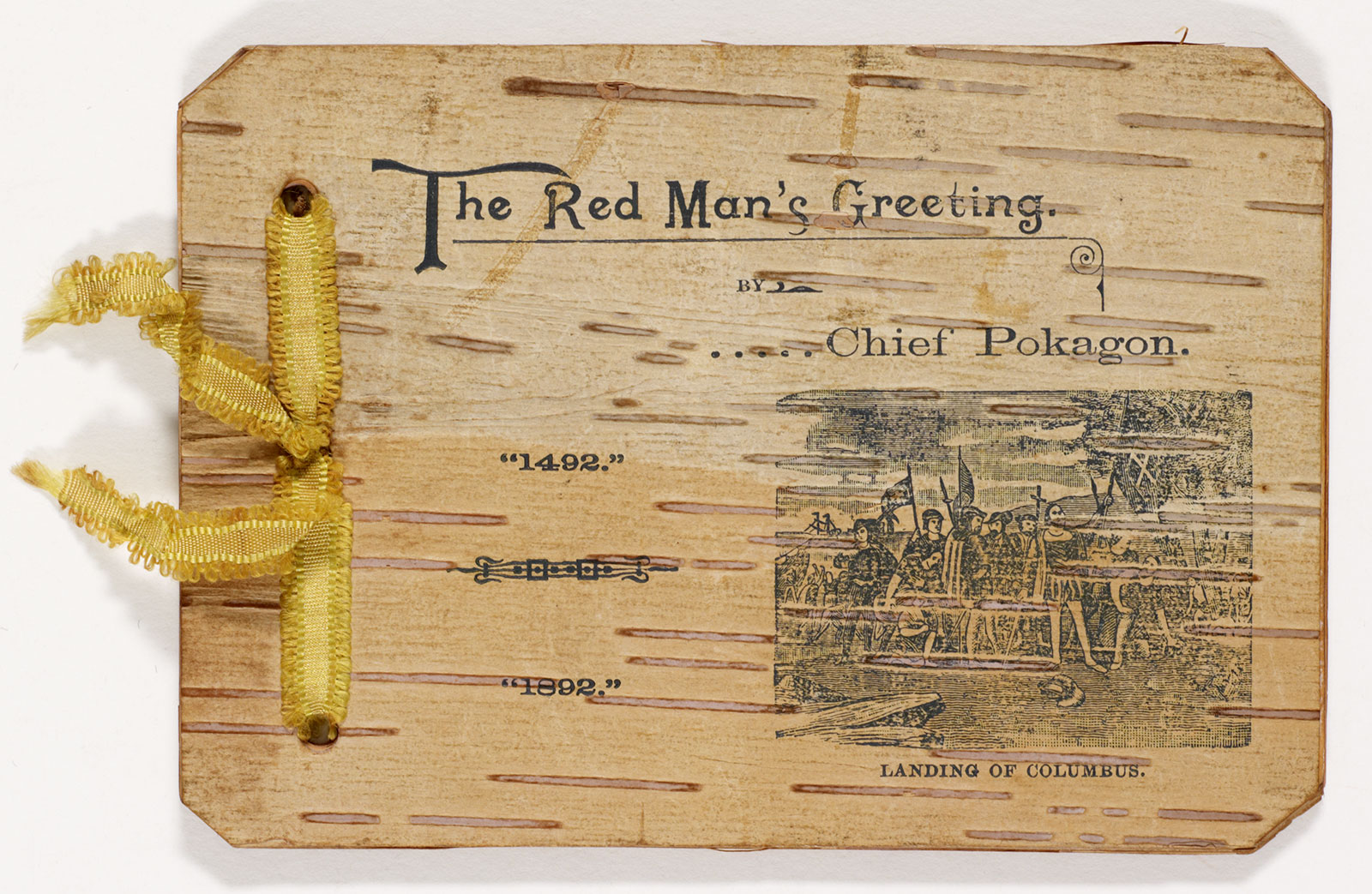

Chief Pokagon's Book

Celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' "discovery" of America, the city of Chicago organized the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. Simon Pokagon, a chief of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians of the Great Lakes region, chastised organizers for stereotyping depictions of Native Americans on admission tickets and in fairgrounds sculpture, arguing that these portrayals ignored his people's contributions "as if nothing that we had done—or given or given up—had contributed to America."

His criticisms found voice in a scathing pamphlet titled Red Man's Rebuke, which he published to remind fairgoers that his own people had "no spirit to celebrate…our own funeral, the discovery of America" with the "pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes." Pokagon's fiery reproach was afterwards reprinted on the bark of a white birch tree and distributed as The Red Man's Greeting. It included the author's poetic lament to his people and their traditions, which, he noted, were "vanishing from our forests," like this tree. To deflect any negative publicity, organizers invited Chief Pokagon to speak at the fair on October 9, 1893. Although dressed in a modern suit, he wore a feather headdress in tribute to his native heritage as he addressed a crowd of 75,000.

Red Man's Greeting provides a rare Native American perspective of a world's fair, occasions that often appropriated indigenous imagery and culture to celebrate European conquest of the New World. Pokagon's "rebuke" dovetails nicely with other Wolfsonian artifacts, including a series of children's books written by educator Ann Clark, illustrated by the Navajo artist Van Tsihnahjinnie, and published by the Bureau of Indian Affairs that incorporated native voices and folktales in both the English and Navajo languages.

– Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

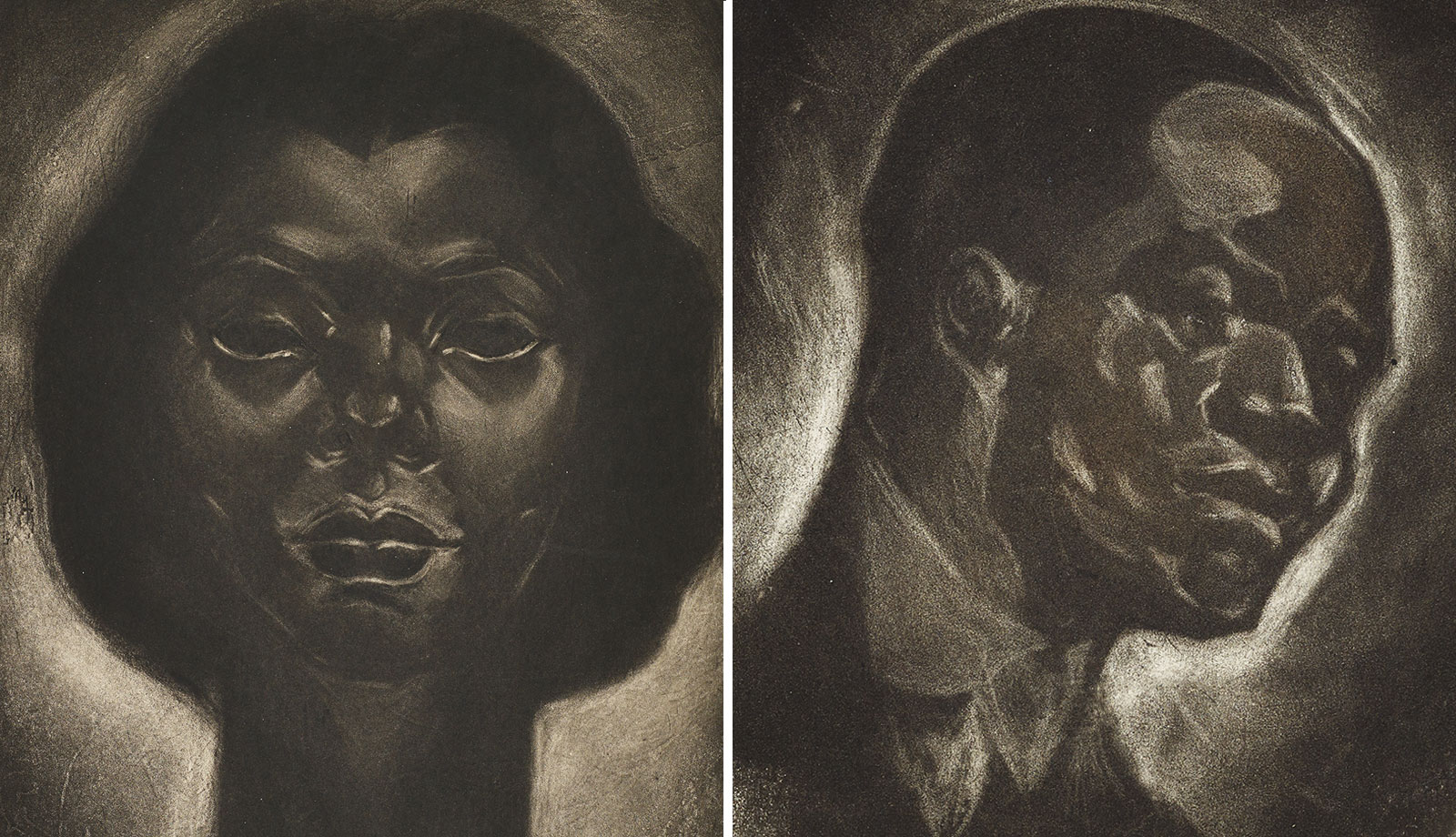

Dox Thrash Prints

Miss X is one of several portraits in the Wolfsonian collection by African-American painter and printmaker Dox Thrash. The enigmatic female face is generally identified with Edna McAllister, Thrash's future wife, and could be the counterpart of Mr. X, an earlier self-portrait by the artist. Edna, a dressmaker in Philadelphia, was introduced to Thrash by his lifelong friend, African-American painter Samuel Brown (1907–1994), whose portrayal, Samuel, is also documented in our collection. Thrash's distinctive portrait heads delineate images of individuals proudly affirming their Black identity. The frontal depiction of Miss X captures the dignified bearing of the woman with her elongated neck and her sculptural features, while Samuel is represented looking down in a meditative pose. Thrash used a particular printing technique, the so-called carborundum mezzotint, that allowed him to surround his subjects with a dramatic aura of light and shade. He elaborated this new printing process in 1937 with fellow WPA artists Hubert Mesibov and Michael Gallagher at the Fine Print Workshop of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project in Philadelphia. Using a carbon-based abrasive on copper plates, Thrash created a print image that allowed a broader tonal variation and a richer chiaroscuro, as seen in these two portraits.

Born in Georgia, Thrash left home as a teenager to pursue an artistic career. While working, he attended night classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, and during the First World War he fought in France. After he settled in Philadelphia in 1926, his work began to earn public recognition in the 1930s. At the beginning of the Second World War, like many other WPA artists, Thrash left the Fine Print Workshop. He applied for a job as an insignia painter on aircraft at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and though a war veteran, he was denied the job because of his race.

– Silvia Barisione, Chief Curator

Credo Altar

Viennese sculptor Annie Eisenmenger created this massive ceramic triptych altar for an international exposition of modern Christian art in Padua, Italy in 1931. Depicting the coronation of the Virgin Mary in its central panel and scenes from the life of Christ at either side, the triptych folds neatly for travel, its closed doors spelling "Credo" in bold, interlocking, wrought-iron letters. A brief mention in a 1932 Viennese publication stated that the work had been universally applauded.

Annie went on to produce work throughout her life. She collaborated with Konrad Lorenz, the Nobel Prize-winning founder of the study of animal behavior, illustrating his book Man Meets Dog. In 1960, she created a mosaic mural of Saint Francis of Assisi at the Schoenbrunn Zoo in Vienna. Despite Annie's many accomplishments, there is little known about her; it is almost as though she didn't exist. Even her date of death had never been correctly recorded, leaving a void in her biographical data. Fortunately, after tracking down her great niece, who was able to provide her actual death date, we updated the Zentralfriedhof—Vienna's central cemetery where Annie is buried. The fact that Annie had almost disappeared from the historic record underscores the enormous challenges facing women, especially in the early 20th century, as they struggled to navigate within a patriarchal, gender-biased culture. As The Wolfsonian moves forward in growing its collection, we will continue to seek out women artists, so often overlooked and sometimes even forgotten, and bring their stories to light.

– Lea Nickless, Research Curator

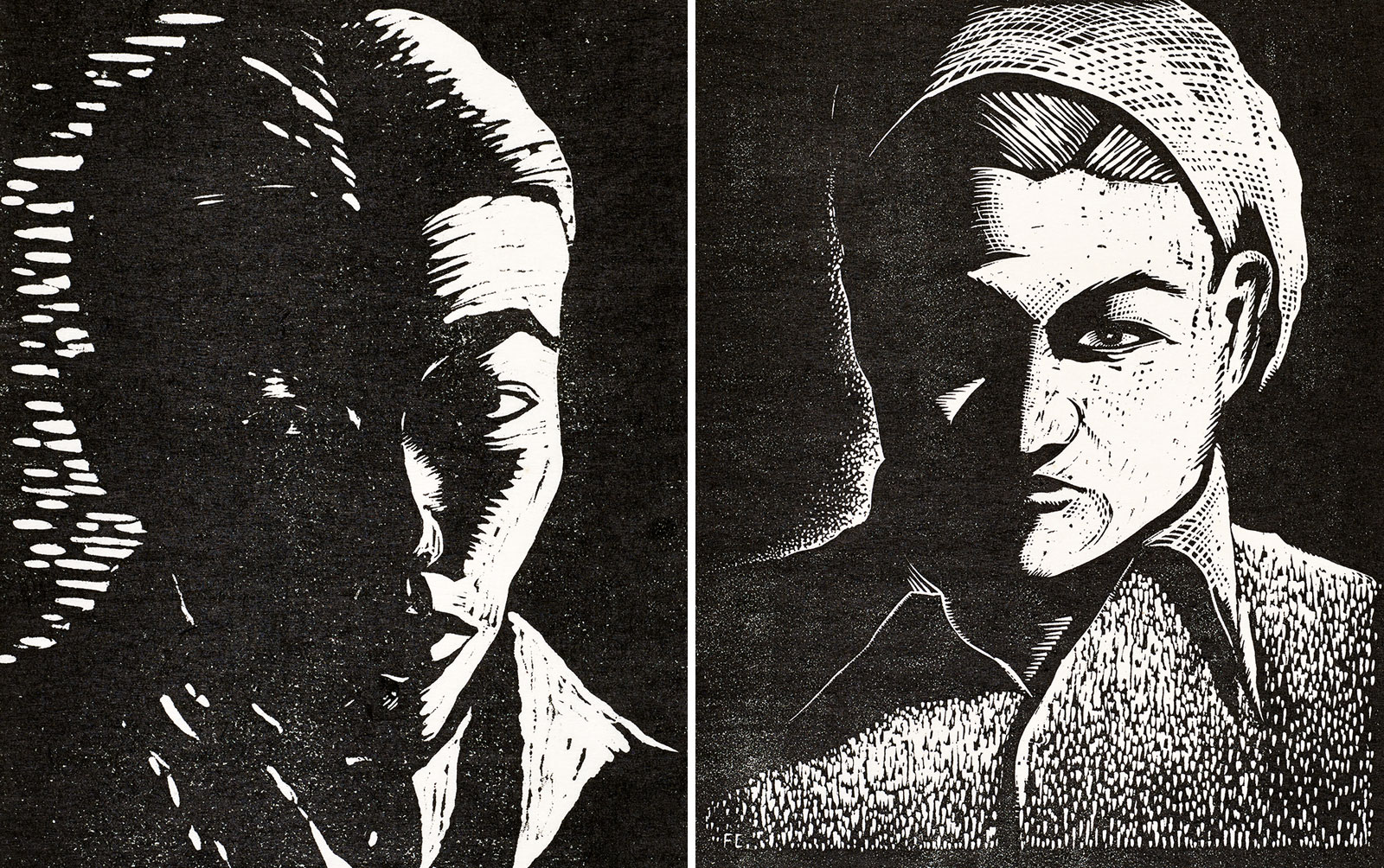

Fay Chong Portraits

As historians and critics have become aware of how art world institutions exclude or diminish people from marginalized communities, some have strived to expand our understanding of which artists from the past "matter." One example is Fay Chong, whose family immigrated to Seattle from Canton in the 1910s, a time when Chinese Americans faced discrimination that had its roots in the previous century. A just-published article by art historian James L. Ellis argues that Chong, together with his friend Andy Chinn, deserves recognition alongside the white men who are celebrated as leading artists of the Pacific Northwest.

The two friends helped form a Chinese Art Club in Seattle in the 1930s. Later in the decade, they both joined the Federal Art Project, a New Deal program that gave paying work to artists. These linocut portraits date from that period. Ellis's article focuses on landscapes they produced just before and after the Second World War, when they injected elements of Chinese techniques—mixing inks and watercolor and painting on rice paper—into their work. Ellis asserts that Chong and Chinn, together with other artists of Asian descent, contributed much to the development of the Northwest School, a regional variant of Abstract Expressionism. But these artists have remained in the shadows, while almost all the acclaim went to four white artists (Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves, and Mark Tobey) with whom they associated and who learned from them. As we continue to enhance our knowledge about our collection, I suspect that we will uncover more artists and designers who are overdue for recognition.

– Jon Mogul, Associate Director of Research, Education + Grants

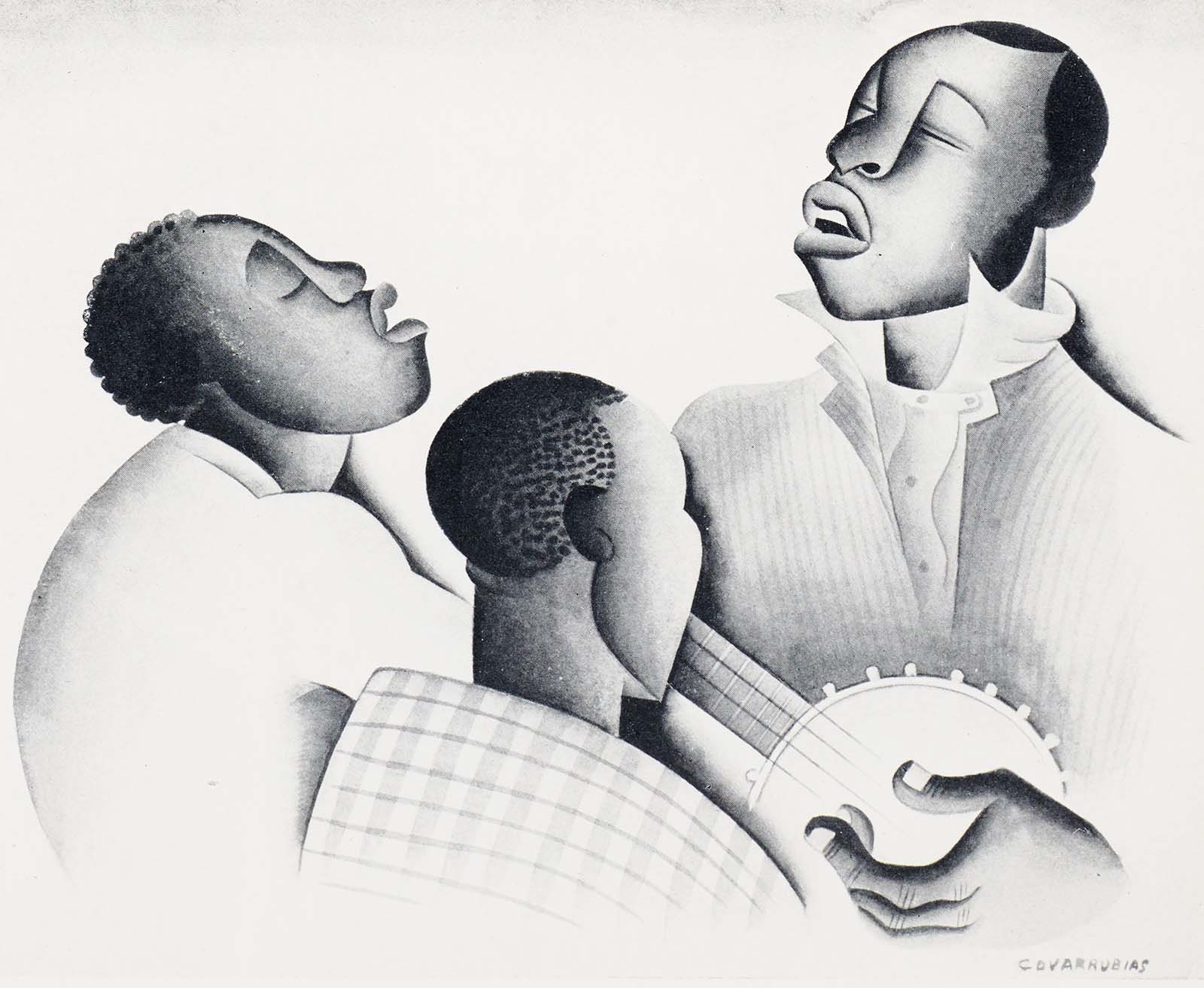

W. C. Handy's Blues: An Anthology

Among the volumes donated by Daniel Morris of Historical Design, New York, documenting the richness of African-American culture in the pre-Great Depression years is the first edition of W. C. Handy's groundbreaking Blues: An Anthology—Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs. Published in 1926, this book adds an "auditive" dimension to the literary and art works of the Harlem Renaissance held by our library.

One of the most influential songwriters of the United States, William Christopher Handy (1873–1958) was a composer and musician who referred to himself as the "Father of the Blues." His anthology records, analyzes, and describes the blues as an integral part of the South and the history of the U.S. Through this work, he elevated the blues from a regional music style with a limited audience to a new level of popularity that spread throughout the whole country and beyond. Handy's book is noteworthy for its contribution to establish the blues, rooted in the experience of African Americans, as a quintessential form of modern American music in the 20th century. Handy's anthology included modernist illustrations by Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, who contributed with drawings and other graphics to several of the books produced by Harlem Renaissance authors.

The Harlem Renaissance is an active area of focus for the library team as we seek to further develop our collection strengths and provide FIU's American literature and cultural studies students with rewarding primary sources for their academic research.

– Niki Harsanyi, Associate Librarian

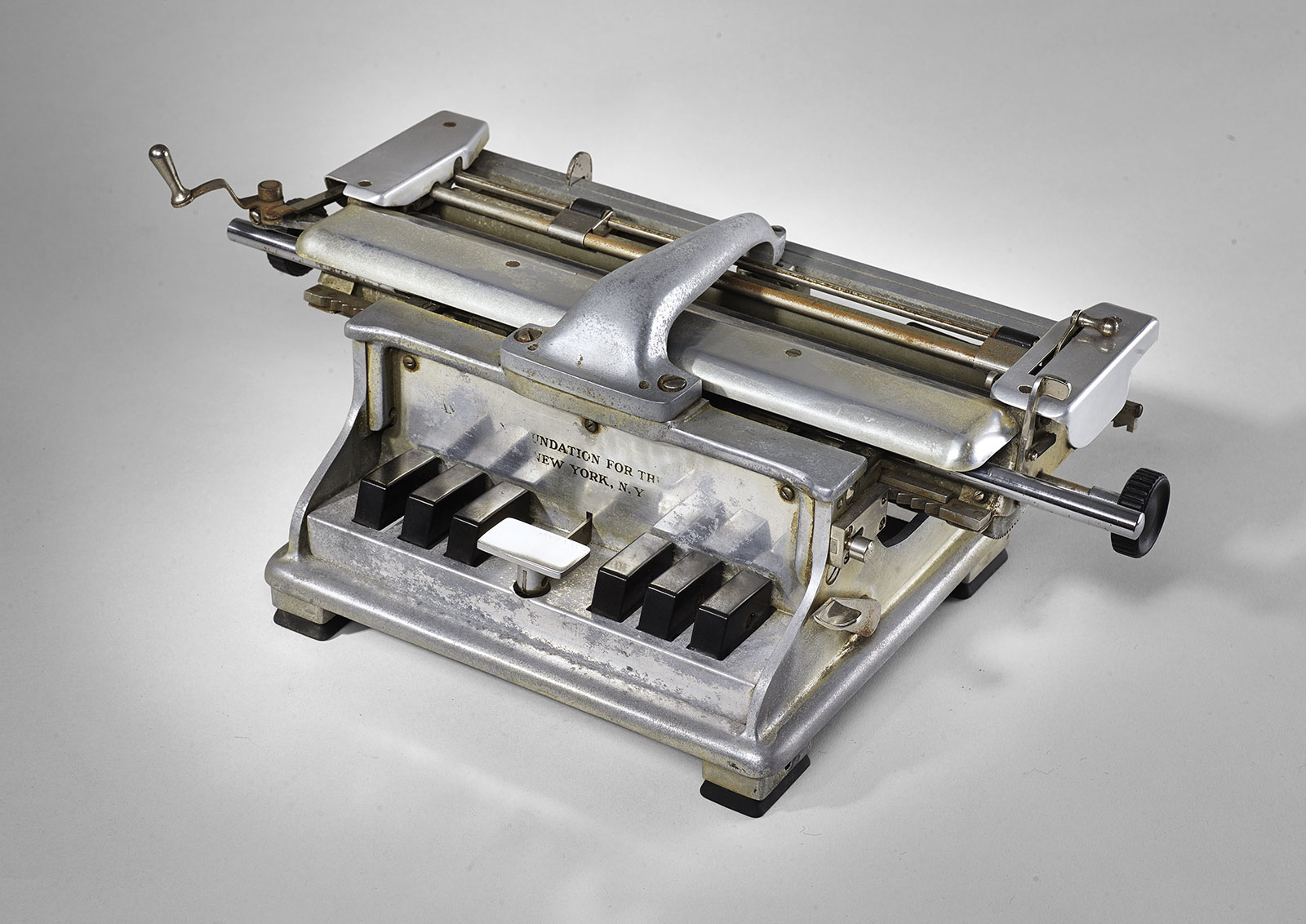

Braille Writer

Here, a Braille typewriter is a pathway into the support network available to visually impaired Americans in the first half of the 20th century. Unlike standard typewriters, Braille "writers" do not produce letters—instead, Braille is a tactile system of raised dots that form a code that can be used across languages. Production was often supported by community organizations such as the Lions Club, which sponsored the development of a 1928 "pocket Braillewriter" manufactured by IBM, or The American Foundation for the Blind, whose research and experimentation led to the Foundation Writer. Manufactured by L.C. Smith & Corona Typewriter Company, the design incorporated a paper roller, back space key, and a levered return. Because blind and visually impaired people were not considered a large consumer base, these manufacturing innovations required the support and financial commitment of nonprofit organizations—a reminder of the role of community action in making real change in the lives of everyday people.

The category of "disabled" is the only marginalized—and protected—class that anyone can enter at any moment in their lives. Disability makes itself known explicitly in objects like the Foundation Writer, but it is also woven into the Wolfsonian collection in ways far less obvious. For instance, the injuries that would require a soldier in the Second World War to need Charles and Ray Eames's plywood splint might lead to disability, while our many workplace safety posters remind viewers of the potential for permanent harm. As we continue to grow the collection, our staff look to add more objects like the Foundation Writer that show the autonomy and community of people with disabilities.

– Shoshana Resnikoff, Curator