September 30, 2020

By Curators Lea Nickless and Shoshana Resnikoff

"The fascination of The Wolfsonian is due to its inversion of what the visitor expects. No logical narrative. No museum formality. No transit code. No prescribed ethic. The Wolfsonian is as equivocal as life itself. In short, not recitations, only information and the hope for understanding—at best, iridescent."

– Mitchell "Micky" Wolfson, Jr., August 18, 2020

Recently, Wolfsonian curators Lea Nickless and Shoshana Resnikoff spoke with collection founder Micky Wolfson about the history of the institution, the continued importance of objects in an increasingly digital world, and why he thinks the museum is more relevant than ever to contemporary visitors. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Lea: Given that the Wolfsonian collection ends at 1950, in what ways do you see it being relevant to people today? How can the collection be something that connects with visitors in their daily lives?

Micky: The Wolfsonian is a secular assembly for the understanding of peoples—a cult of curiosity. It is a presentation, through objects, of the immediate past imperfect. We wade through this documentary information and we begin to see that the references of our period (1850–1950) still resonate with us and with the human condition today. It's closer to us than a distant past, so we can see it as well as hear it through the language of objects presented. The collection provides evidence of our recent past, removed by only a few generations. You can disguise the past—the past perfect—but you can't disguise the immediate past, because it is imperfect. We know that, we are haunted by that, and we still refer to it in our daily lives.

This is what Thomas Friedman meant when he recently commented in The New York Times: "For me, this is our generation's D-Day or E-Day. Think about it. The American soldiers who landed on Normandy Beach, under a barrage of Nazi artillery fire, on June 6, 1944, were actually voting with their lives so that the rest of us could vote with our ballots—in person or by mail—in every election from that day forth, even if it was in the middle of a pandemic."

So the references are eerily close to hand. The period of The Wolfsonian's collection provides references for thinking about the world today, imperfect as it may be. The Wolfsonian offers a radical form of visual study.

Lea: You talk a lot about the language of objects, how they can be read and heard and understood. Can you speak more to that?

Micky: The objects are a bridge between you and me, and between older and younger generations.

Shoshana: What I think is so interesting, Micky, is that you argue for digital engagement with the recent past but maybe it goes in the opposite direction as well—that there's something that young people today can learn from objects that they can't necessarily learn from the digital world. I'm a Millennial and not so far from those considered "digital natives," but I'm wondering how you see objects speaking to my generation or to Gen Z?

Micky: This is why younger visitors have to learn from the language of objects. Because you are the experiential generation, you are now trying to reconstruct your parents' world. Because you missed it, it lapsed—your parents and grandparents wanted to be done with it . . . . After the Second World War, we were protected. We were told we could forget the past. We could forget it because the new world was arising. We were free, and what were we free of? A past that wasn't pretty. The Europeans let it go. The Americans let it go. They drew the curtain down, marking a demarcation—then and now—and giving us a false sense of assurance and righteousness about the past. "You don't need to investigate that; it's over and done with, no need to worry." And now we're trying to raise the curtain so that you can experience that period, and understand the forces—good, bad, and ugly—that shaped your ancestors, your parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents.

Shoshana: What role does the collection play in remembering, particularly for younger visitors?

Micky: It confronts you, it challenges you, it provokes you, it invites you for a new experience. Millennials and Generation Z want to experience everything immediately, they want to be engaged. With The Wolfsonian, the subject is the recent past, where the lives and motivations of people, while different from ours, are at least somewhat familiar to us today. It's only 100 years ago—you're just stepping one foot backwards, not ten.

Shoshana: I think young people—my generation—we're looking for meaning. Maybe I should just speak for myself, but I often feel that I was born into one world and have now grown up into a very different one. I think that disjunction drives us to make sense of the world, and of the past.

Micky: Absolutely, and that's what The Wolfsonian attempts. Objects are terribly helpful because they exist concretely. And if you see things that are concrete, you can understand them better than if they are abstractions. They can be a language of communication, one that young people understand because they are sophisticated and critical viewers of images and objects. Objects act as a bridge to meaning, both the good and the shameful. They can expand one's worldview.

Lea: And do you think that it's important for The Wolfsonian to confront visitors with the uglier parts of history?

Micky: Well, I never mean to be inflammatory, I mean to be provocative. But we are not dictatorial, we do not impose. I'm not going to tell visitors what to think. That's what historians and literary figures do. The Wolfsonian is a novel! We don't tell people how to read the novel or tell them the moral of the story, but we present the picture in all its angles, and that includes darker moments. You mustn't reject the shameful, you must learn from it.

Shoshana: So it's not just about a dark past.

Micky: The Wolfsonian is about engagement with life. It documents the vicissitudes of human nature. It expresses human longing, curiosity, creativity. It is only through rigorous scrutiny of our individual, communal, national, and global identities that we can gain understanding and new perspectives. Ultimately, our goal is tolerance and understanding—an understanding of human nature, that none of us is static, and we never were.

Lea: Tell us about your relationship to Miami Beach. Why did you make this city The Wolfsonian's home?

Micky: Miami Beach is a modern microcosm of the larger world, a reproduction of style, a glamorous invention paralleling The Wolfsonian's time period. I was lucky—my family was part of the early fabric of this community, my father serving on the city council and then becoming the first Jewish mayor of Miami Beach. I was born at Jackson Hospital, brought home to Pine Tree Drive. I was a small child when my father went off to Europe to fight the noble fight in the Second World War, and Miami Beach became a training ground for the army. In many ways, the story of Miami Beach and the story of The Wolfsonian are very similar—struggle, growth, war, economics, multiculturalism, etc.

Later, as an adult, I wanted to participate in expanding the cultural offerings of Miami Beach—hence The Wolfsonian. It was enlightened self-interest!

Lea: What is the future of The Wolfsonian, as you see it?

Micky: I've spent a lifetime reaching out for "things," for objects, which lead to meaning. Now I think that evolution means looking forward and also looking closer—at the collection, at history, and at the past and present. This cultural evolution will be the main driving force for the future. Ultimately, though, this is an intuitive institution, an entity full of people constantly learning, just as in life. And that learning that we do, we do for the visitors, so that they can join in the discovery.

The Wolfsonian provides the raw materials for interpretation, references, and connections. So if we can guide someone to think "I never thought of that," or "I never knew that," or even "I see that reflected in my own life," then we've succeeded.

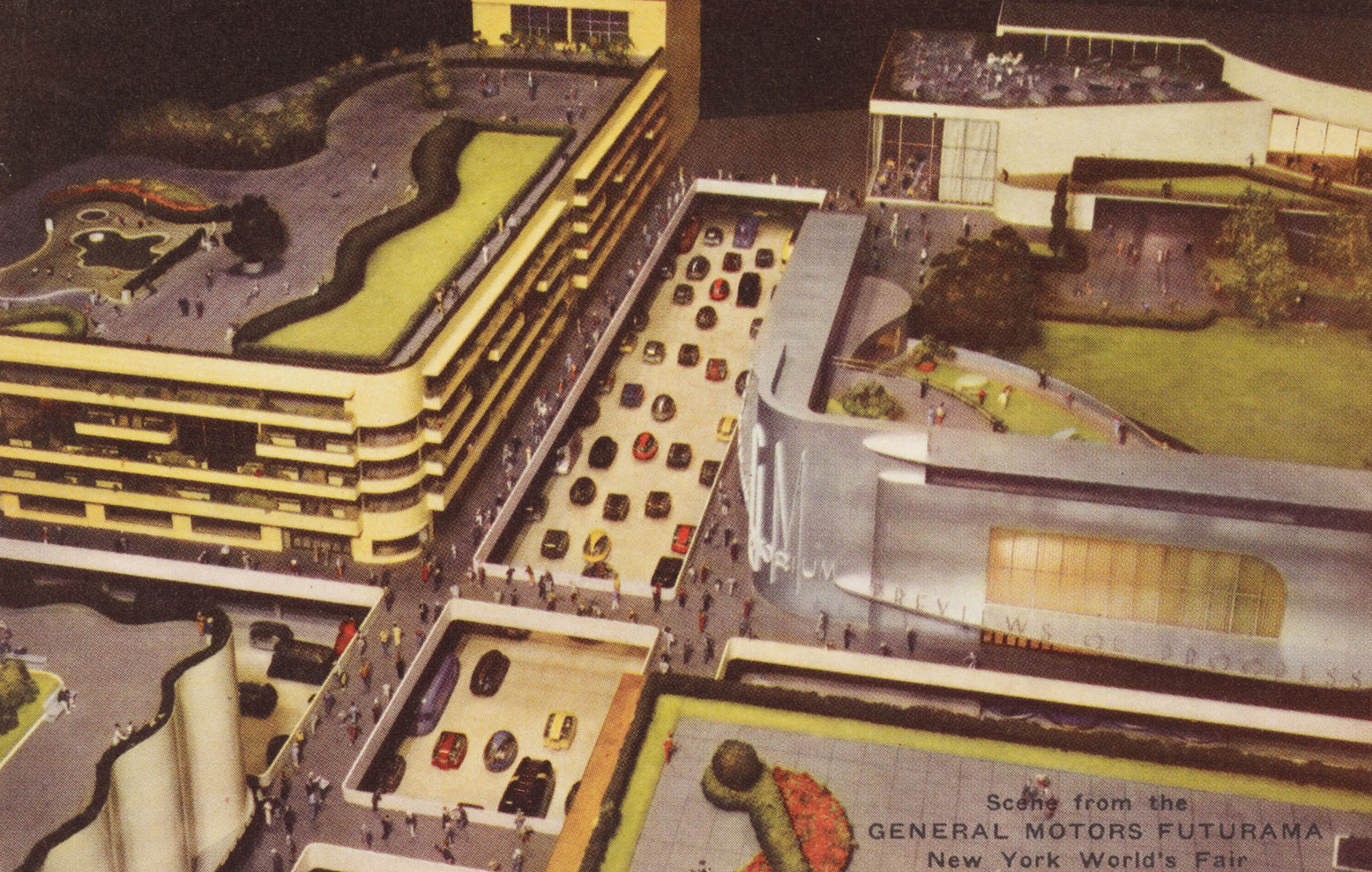

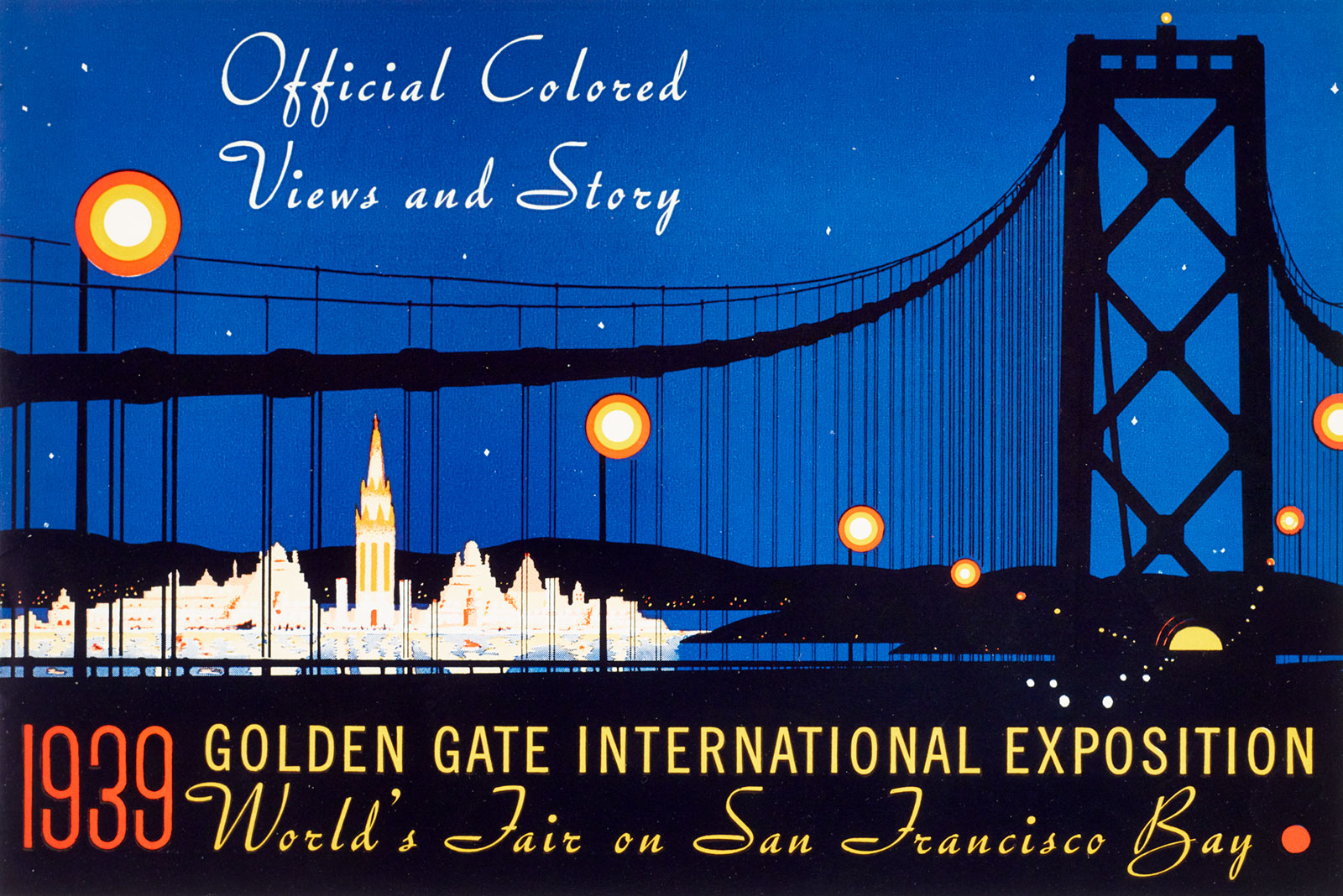

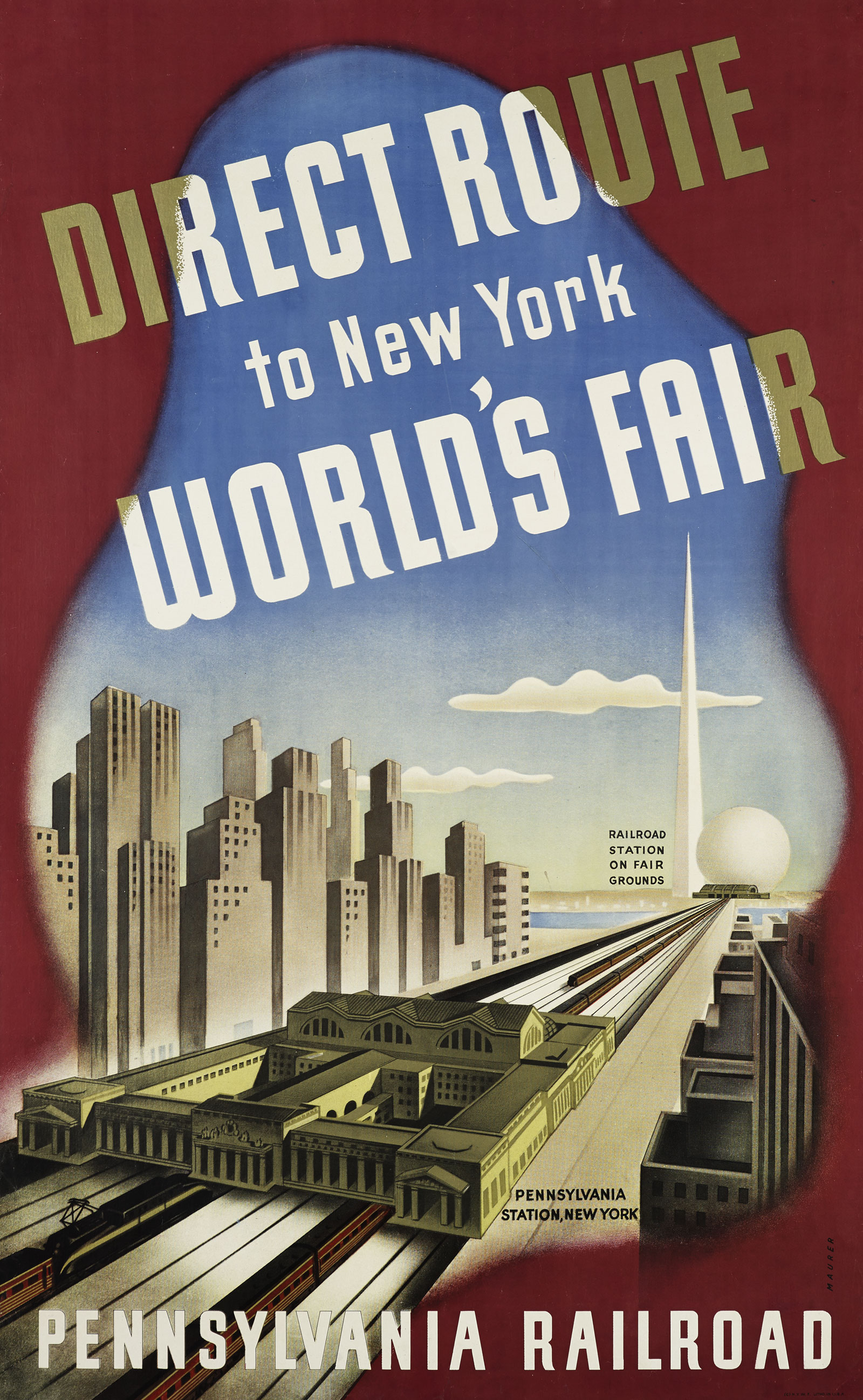

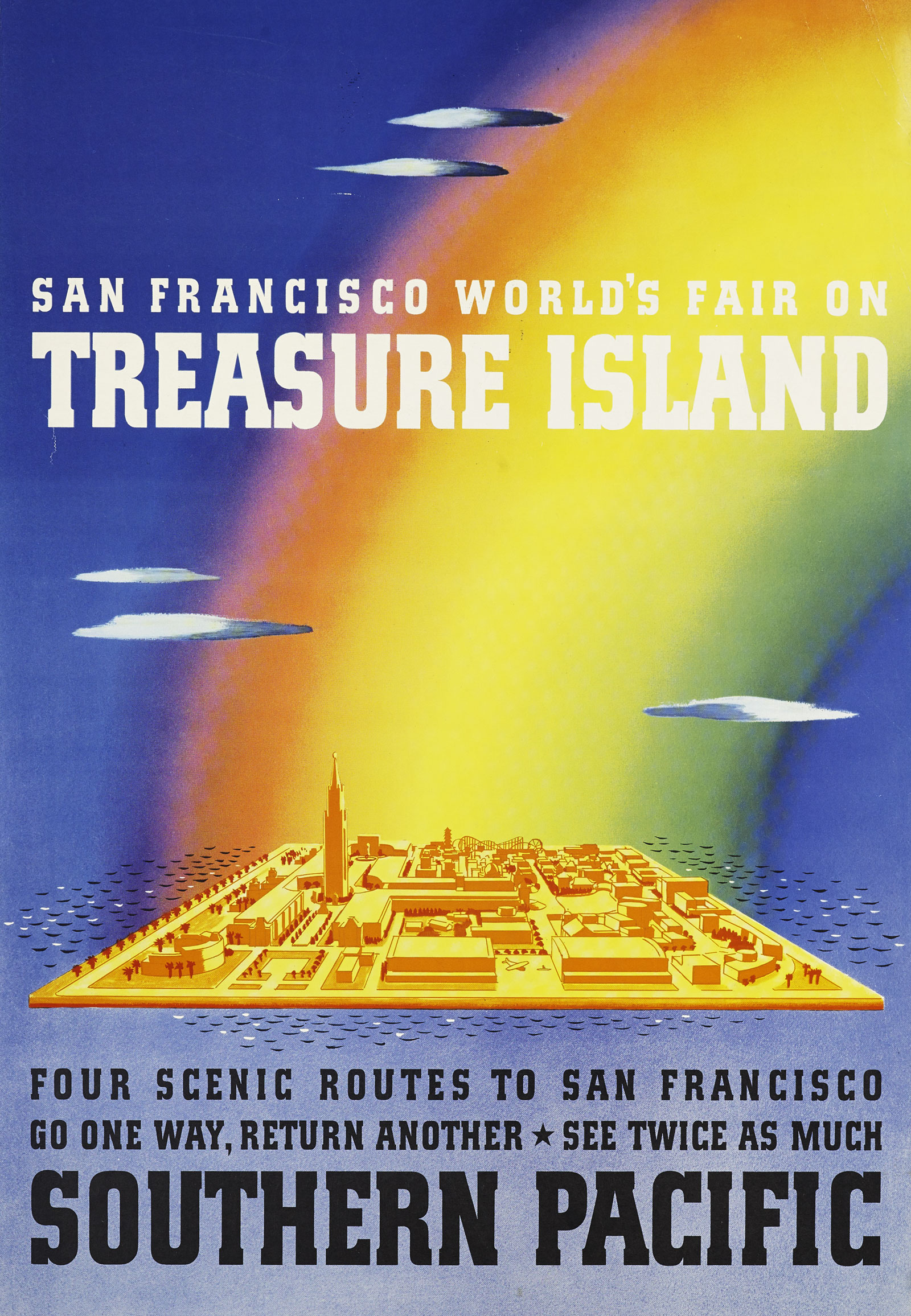

Images in this blog post were taken from Wolfsonian collection holdings from the 1939 world's fairs, one in San Francisco and the other in New York. The two fairs remain significant in both social and design history for their impact, as they helped to define the look and feel of the future in the minds of hundreds of thousands of fair visitors. 1939 is an important year to The Wolfsonian: it saw the outbreak of the Second World War and is also the year of Micky's birth.