August 21, 2020

By George Leyva, visitor services associate

This year will undoubtedly go down as one for the history books—we've witnessed the eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic; mass unemployment; heated, intense rhetoric surrounding Black Lives Matter; and protests about mask wearing. And since 2020 is a presidential election year, tensions are expected to only rise as we head into fall.

In my almost five years working at The Wolfsonian–FIU, I've seen numerous exhibitions that have helped me understand not only the past, but also the present, from tactics of persuasion to methods of manipulation. In just a few months, Americans will be casting their votes to determine the course of our lives—and our country—for the next four years, a decision that in today's Internet age will require more savviness about the power of propaganda than ever. The three Wolfsonian exhibitions that follow are great means for making sense of these troubled times.

Constructing Revolution

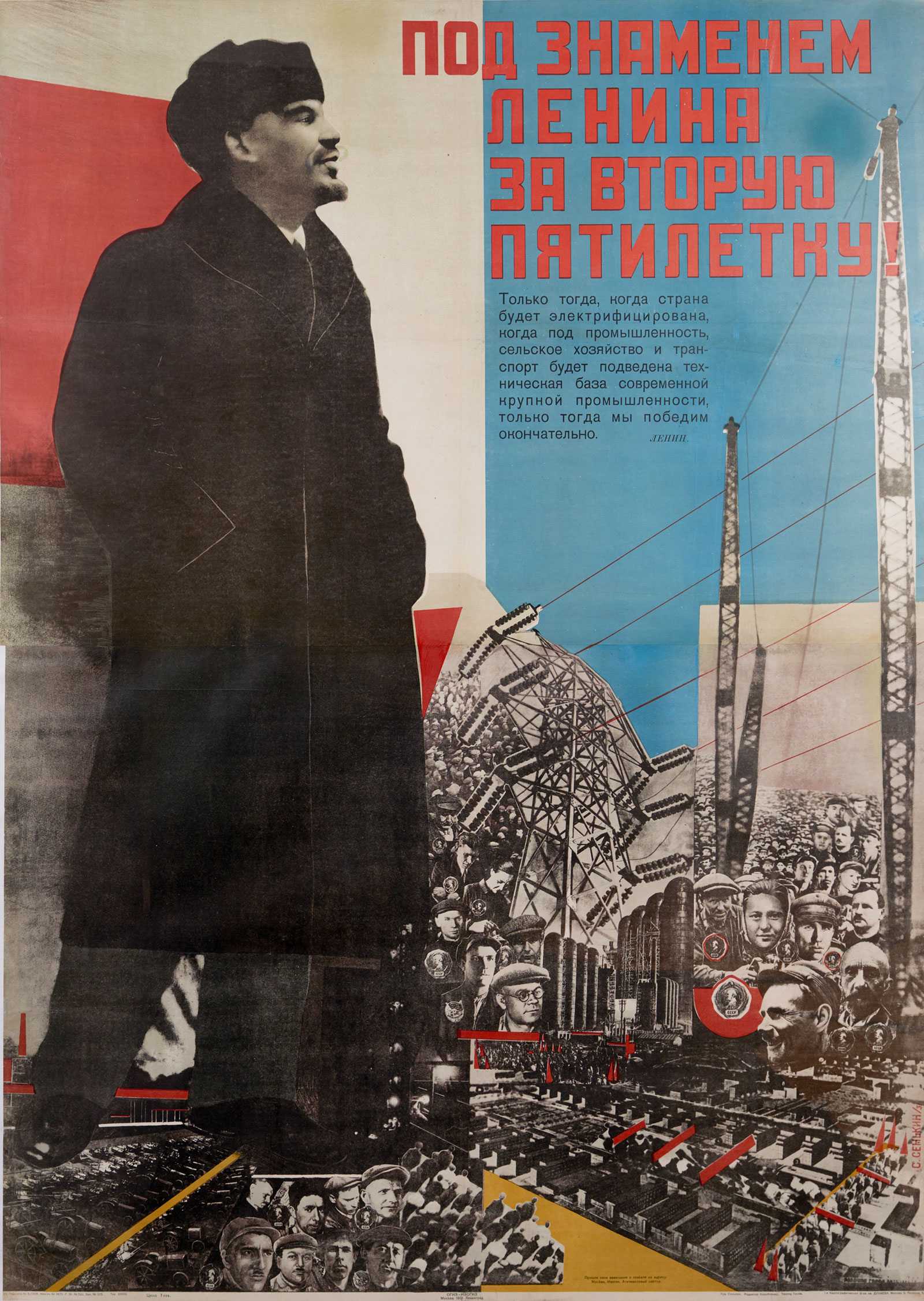

This Bowdoin College Museum of Art exhibition, which traveled to The Wolfsonian in Summer 2018, showcased how propaganda was wielded in the early years of the Soviet Union. Interestingly, there are some connections between this show and the newer forms of propaganda we see on social media and beyond. Take, for instance, a 1931 poster of Vladimir Lenin titled Pod znamenem Lenina za vtoruiu piatiletku [Under Lenin’s Banner for the Second Five-Year Plan]. Designer Sergei Sen'kin used photomontage to portray the late Soviet leader as a larger-than-life figure who was worthy of worship and adoration, thereby contributing to the Lenin cult that grew after his death in 1924.

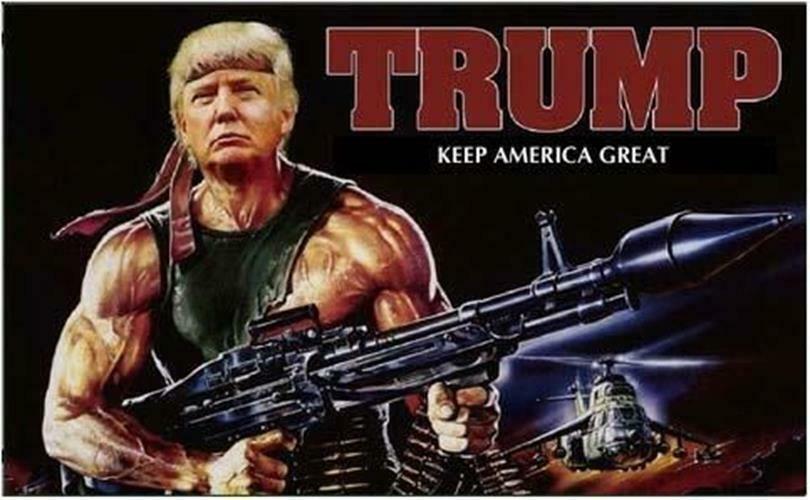

Now compare Sen'kin's poster to contemporary portrayals of major American politicians. Recently, I drove past a rally in Miami Lakes for President Donald Trump and spotted a depiction of him as the fictional action hero, Rambo. Several days later, I saw a similar image at another Trump rally on the local news. Here, President Trump's supporters are using visual techniques to present their candidate as superhuman—dwarfing the helicopter in the background like Lenin dwarfs tractors and cranes in the Soviet poster—and as deserving of acclaim and praise as the popular 1980s Sylvester Stallone character.

The Trump Rocky meme—which even popped up on the President's Twitter feed—has inspired some creative responses from the left; in a version shared in a tweet from Christine Pelosi, daughter of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a manipulated Rocky IV still adds Ms. Pelosi's head onto the body of Rocky Balboa and Trump's to that of the film's Russian villain, Ivan Drago (complete with a Vladimir Putin tattoo for good measure).

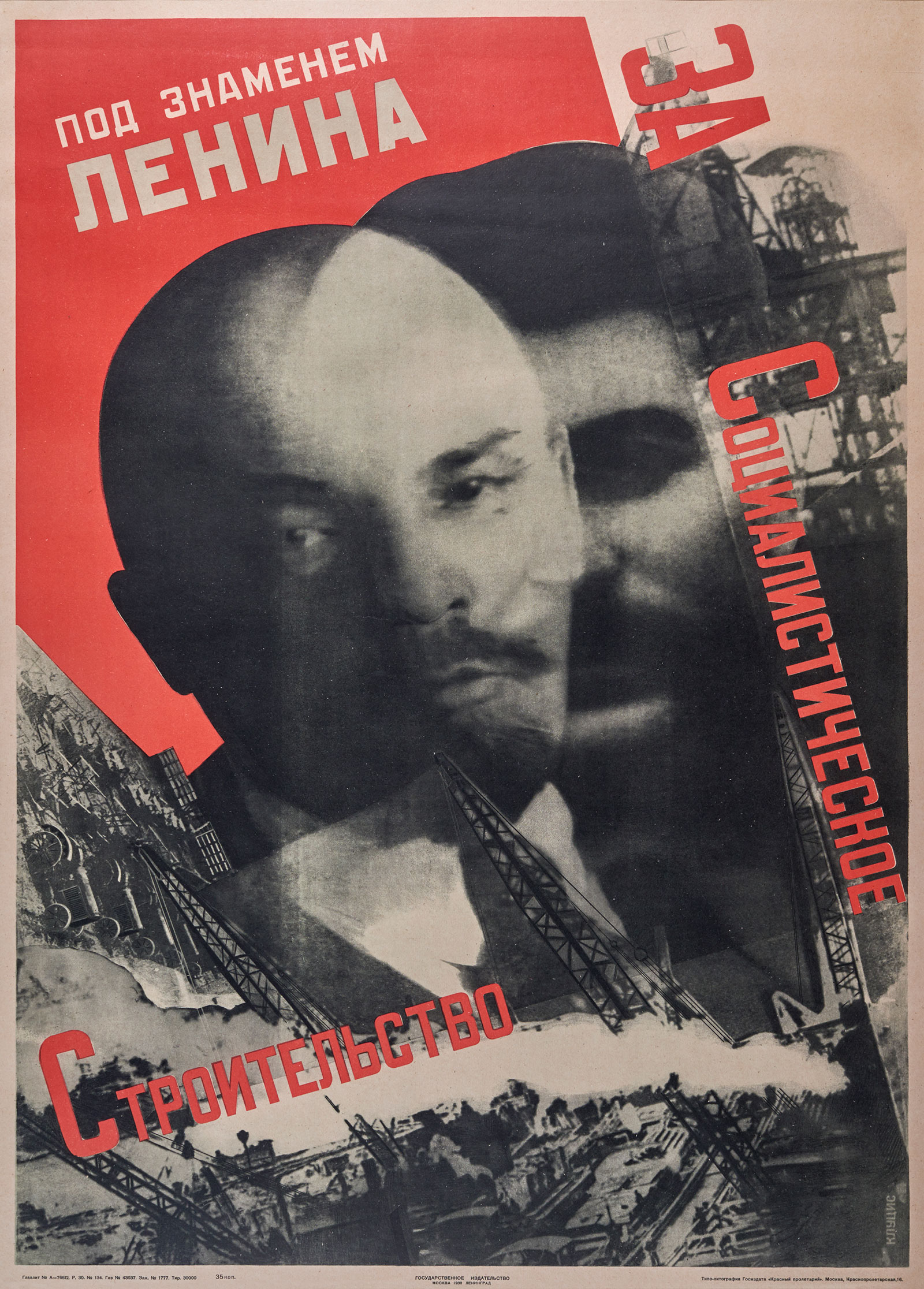

Another parallel is found via photomontage. For example, in Gustav Klutsis's 1930 poster Pod znamenem Lenina za sotsialisticheskoe stroitel'stvo [Under Lenin's Banner for Socialist Construction], the face of Lenin is joined with that of Joseph Stalin. The visual pairing suggests that both leaders are in agreement with one another—history, however, tells a different story. While initially Lenin and Stalin got along, as time passed their relationship soured.

A few weeks ago, Fox News was heavily criticized for using digitally altered photos in their coverage of Seattle's Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, which was set up as a safe space for demonstrators to protest systemic racism and police brutality. In one photo, a heavily armed individual is shown standing next to a store being looted; many viewers might assume he is playing a part in the destruction. In truth, however, the man was volunteering for Capital Hill Autonomous Zone security on June 10, and his picture was spliced in with two other source photos of damaged Seattle stores taken on May 30. Together, these three photos paint a negative picture of the protests, suggesting that they were violent and something to be feared. So, in the same vein as photomontage, this doctoring of photos combines different images to make an entirely new one—arguably armed with a politically pointed message.

Lastly, I'd like to point to Dmitrii Moor's 1931 poster Khleb nasha sila, interventam mogila: Sobirai urozhai [Bread is Our Strength, (and) the Interventionists' Grave: Gather the Harvest]. In this poster, Moor suggests that female Russian peasants have let go of the tsarist past and accepted the new Soviet order: the women specifically have their scarves tied behind their heads, a newer custom, and not under their chins in the traditional style. Despite the state's portrayal of their acceptance of the collectivization campaign and a harmonious countryside backdrop, history contradicts this; in reality, there was mass resistance, a drop in production, and devastating famine.

Recently, a meme has circulated online of a photo of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden with the late Senator Robert Byrd, in which it is claimed that Biden was pictured with the former Grand Wizard of the KKK. However, as in the case of the Moor poster, the facts offer something different. Senator Byrd was indeed a member of the KKK, but only during the 1940s, when Biden was a young child. Furthermore, Byrd never achieved the rank of Grand Wizard, and he later loudly renounced his white supremacist views and expressed deep regret over his KKK membership; this was all long before the photo in question was taken in 2008. While it's not exactly the same manipulation at play here as in Moor's poster—the photo is, after all, entirely real—the supposed context behind it is miscast to benefit a political agenda.

Cuban Caricature and Culture: The Art of Massaguer

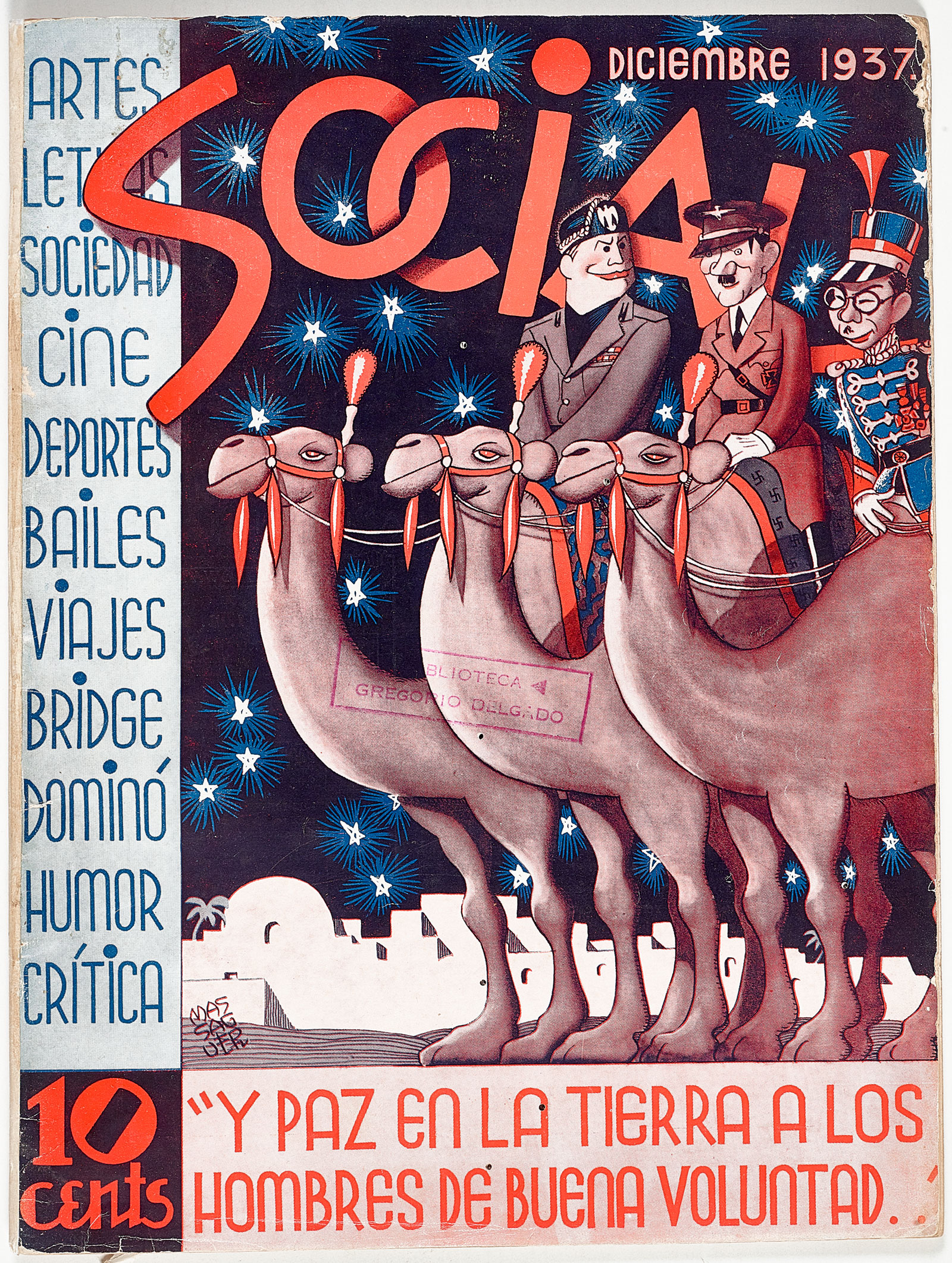

Graphic artist Conrado Walter Massaguer was primarily known for his satirical drawings, which are highly reminiscent of political cartoons from this election year. Take, for instance, the 1937 Christmas issue of Massaguer's magazine Social. On the cover he featured the leaders of the Axis Powers, portraying them as the three wise men from the East. Below, he added the ironic caption "And peace in the land to men of good will"; the militaristic aggression of these three leaders, as we know, led to the deaths of tens of millions worldwide.

In a similar cartoon, Washington Post artist Nick Anderson recently celebrated our country's birth. In addition to commemorating the July 4th holiday, Anderson's drawing echoes the same irony displayed by Massaguer—although he wishes America a happy birthday, he depicts the red stripes of the American flag as graph lines representing out-of-control COVID-19 infection rates. As with Massaguer's piece, Anderson's cartoon may elicit a sardonic chuckle, but the message (that state decisions can have dire human tolls) is very grim: a month later, more than 150,000 Americans have died due to the coronavirus, and the number keeps climbing.

Another Massaguer work worth noting is his 1944 print Doble Nueve [Double Nine]. In it, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill are playing dominoes against dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, with Joseph Stalin and Emperor Hirohito as spectators. By this time, the tide of the Second World War was swinging in the direction of the Allied Powers, a turn of events playfully referenced by sulky Hitler and sweating Mussolini’s foul moods.

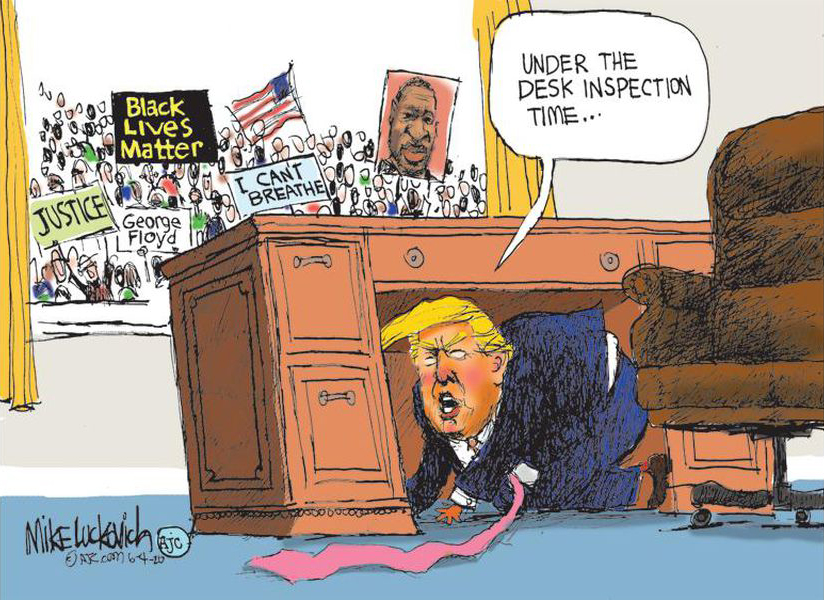

Compare this to a recent drawing by cartoonist Mike Luckovich. Here, President Donald Trump is shown hiding under his desk as anti-racism and police brutality protesters gather outside the White House. The cartoon portrays Trump cowering in fear, much as Massaguer's Hitler and Mussolini are depicted as scared of losing to Roosevelt and Churchill in the game of dominoes.

Another synergy between past and present can be found in the mixture of political figures and popular American products. For instance, Massaguer published a book titled Voy Bien Camilo? [Going Well Camilo?] in 1959, shortly after Fidel Castro took power in Cuba. In the book are caricatures of the revolutionaries enjoying American products like Jell-O, Coca-Cola, and Buick.

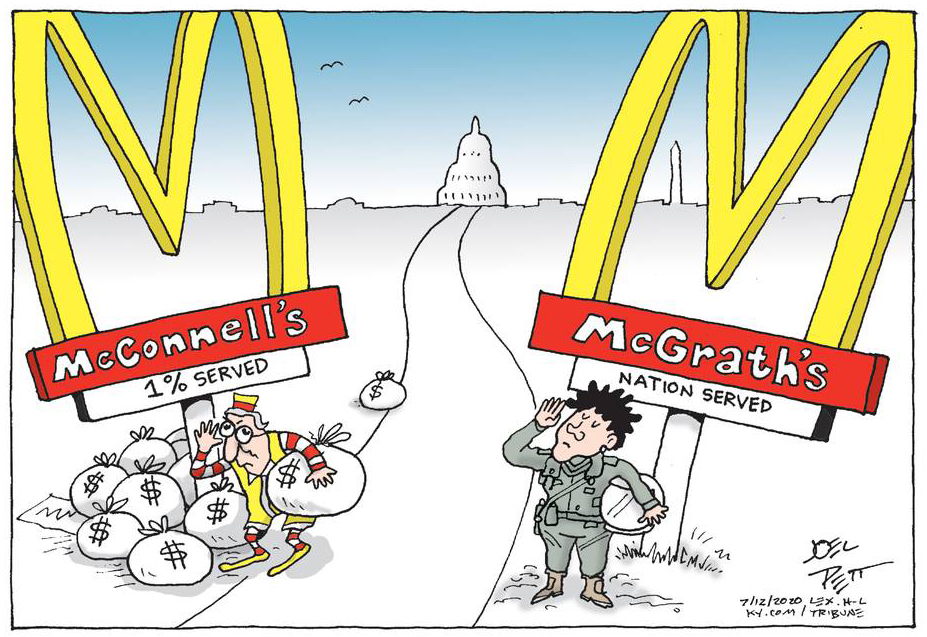

In a similar cartoon from this July, artist Joel Pett uses the McDonald's logo to make a comparison between Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell and his challenger Amy McGrath. Wearing Ronald McDonald's clothes and holding money bags, McConnell is standing under the McDonald's arch (changed to McConnell's) under the caption "1% Served." Across from him, McGrath, a former fighter pilot, is seen in her Air Force gear in a saluting pose beneath a McDonald’s arch touting "Nation Served."

Radicals and Reactionaries: Extremism in America

This last installation—The Wolfsonian's most recently displayed—served to illustrate the volatility of America in the 1930s, when politics reached a fever pitch not unlike what we're seeing today. Take, for instance, William Randolph Hearst, who was spotlighted in Ann Weedon's 1936 pamphlet Hearst: Counterfeit American. Hearst was in charge of a media empire seen by many as promoting right-wing views, an accusation only bolstered by Heart's personal friendships with foreign dictators and preferential editorial treatment of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis when they first came to power. Likewise, many major news organizations of the 21st century—Fox News and The Washington Times on the right, and MSNBC, CNN, and The New York Times on the left—have been framed by critics as mere mouthpieces for one side of the ideological spectrum or the other.

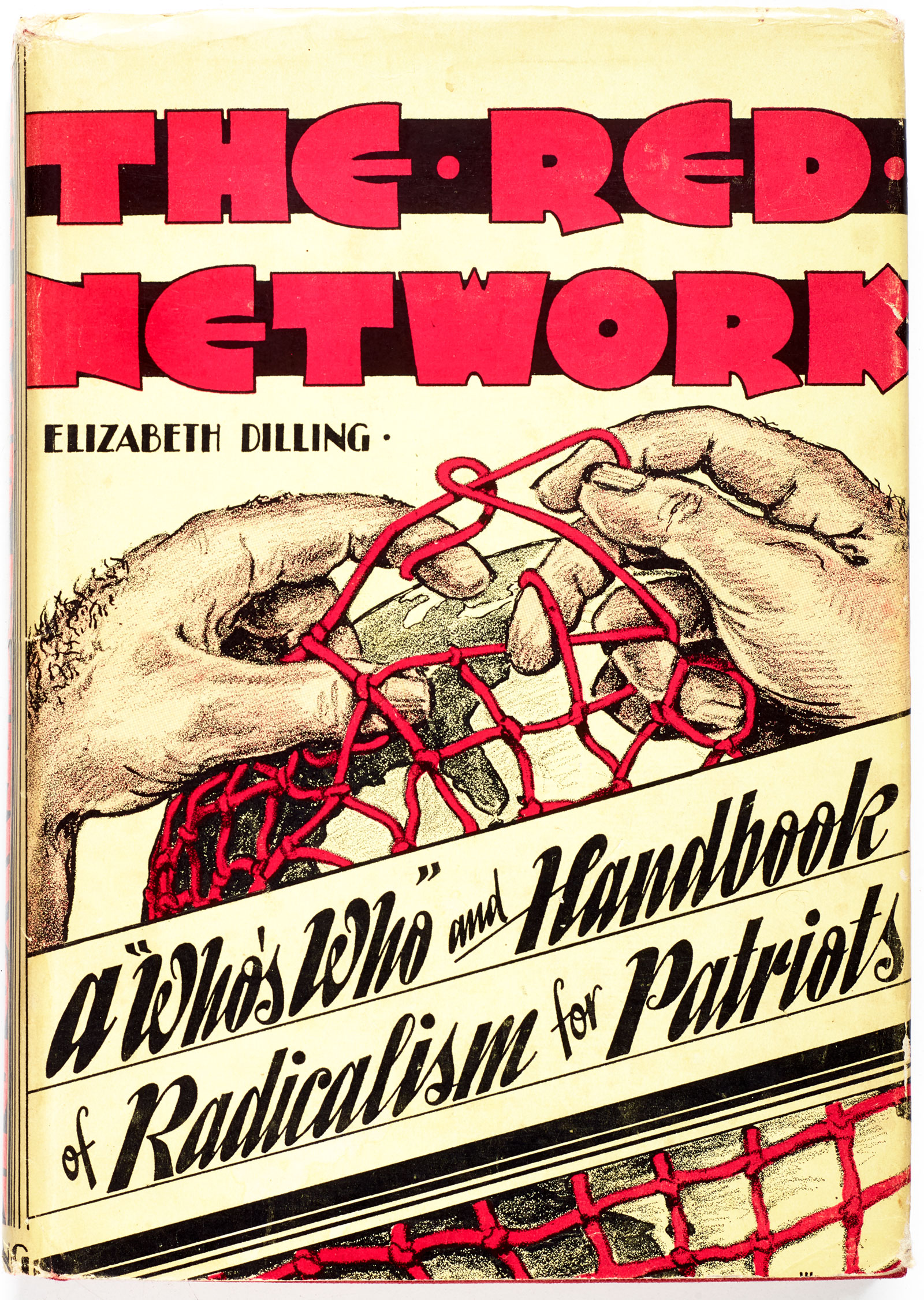

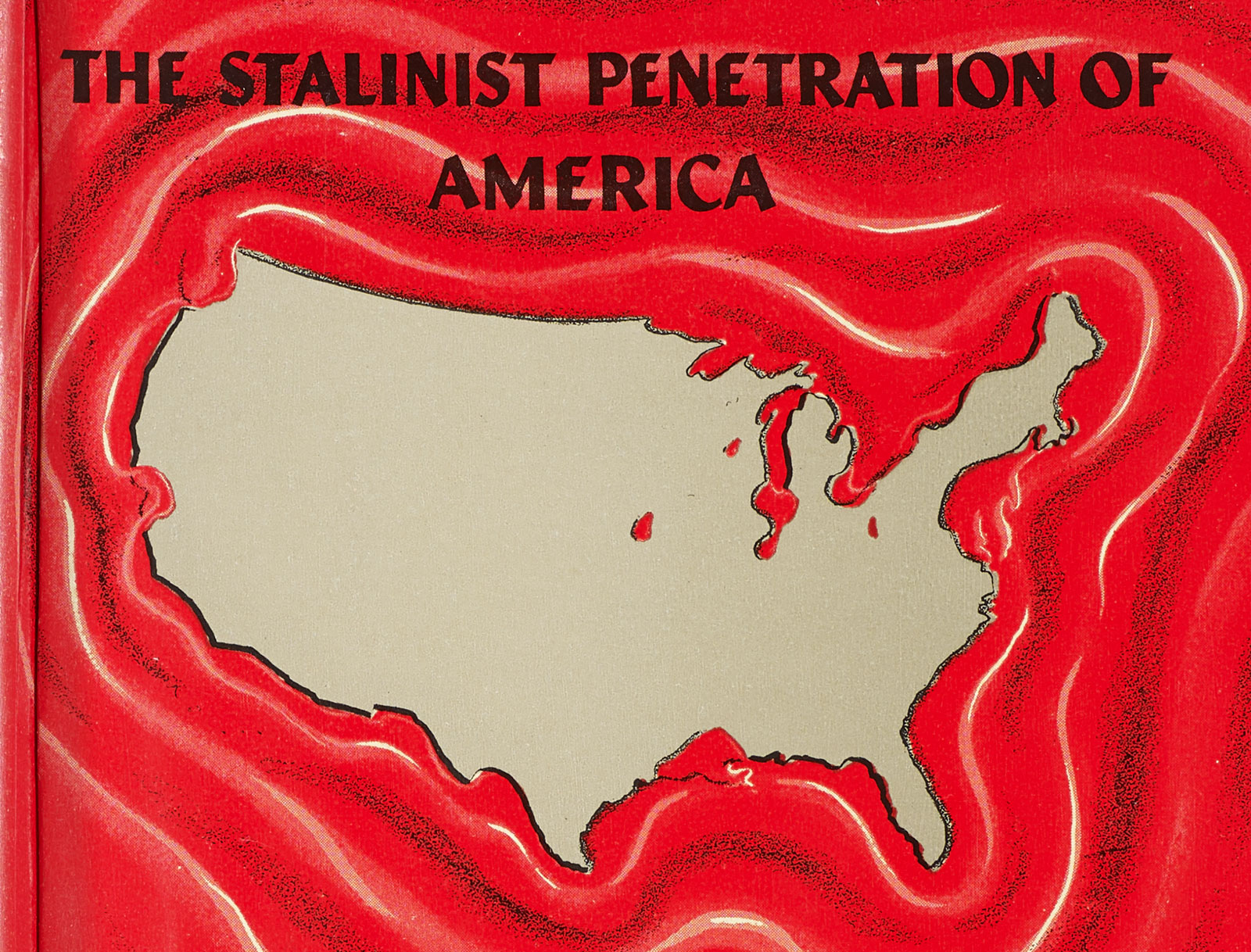

Tactics for scaring Americans about the big bad political "other" are nothing new. In the 1930s, ring-wing books like The Red Network: A "Who’s Who" and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots and The Red Decade: The Stalinist Penetration of America conjured the idea of the Communist bogeyman, warning Americans about the "red menace" trying to subvert American institutions and pointing out individuals and groups that were supposedly part of this plot to undermine the country.

We see this same one-dimensional casting in our media now‚ and in greater volume than ever before thanks to the Internet and social sharing. In the Republican red camp, politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandra Ocasio Cortez are modern-day Communists bent on sponsoring laziness with Medicaid and bankrupting the nation with Medicare for All; and in the Democratic blue, our President and his supporters are all mindless racists. Such thinking and framing leaves little room for shades of gray.

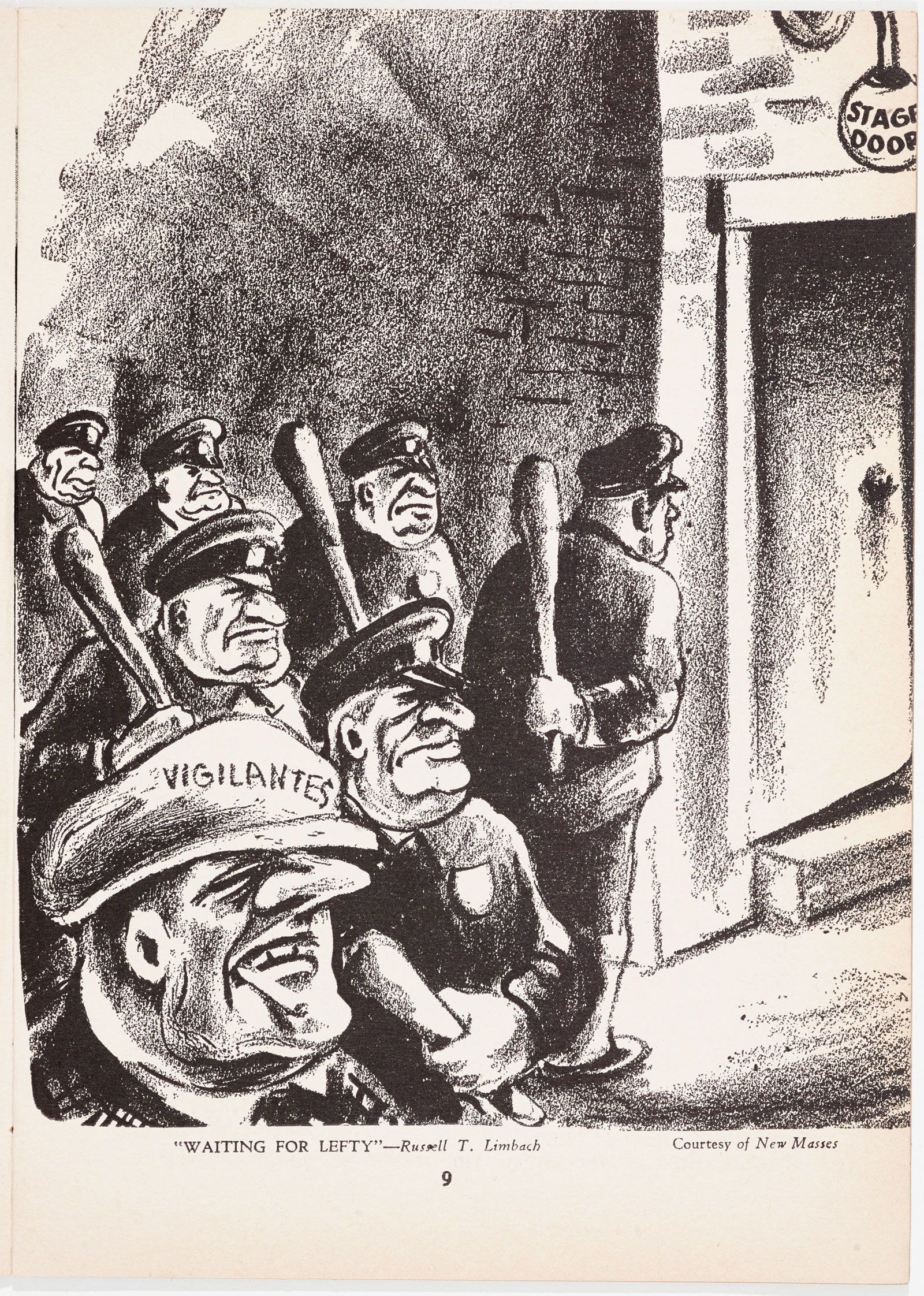

Worries about First Amendment protection are also age-old. For example, the New Theatre League, which was formed in 1935, staged left-leaning plays and came out with monthly publications and pamphlets, such as New Theatre and Censored! The Censors See Red! The Record of the Present Wave of Terrorism and Censorship in the American Theatre, that expressed their concerns over the ring wing's stifling of First Amendment rights.

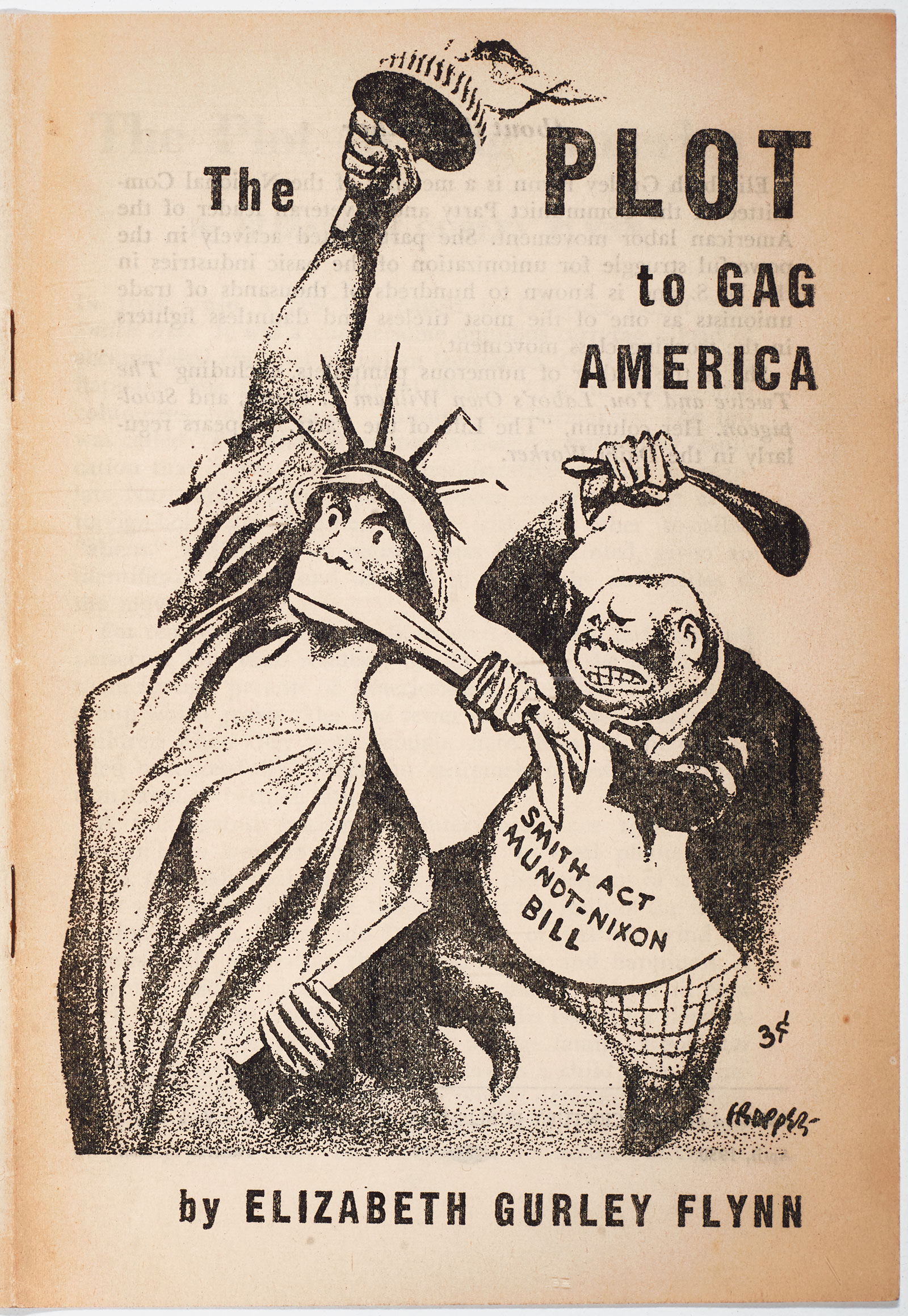

A brilliant depiction of how these groups felt can be found in Elizabeth Gurley Flynn's pamphlet The Plot to Gag America, in which Lady Liberty is being forcefully silenced. Such anxieties are very much alive and well in 2020, with near-constant concern about forces in power stifling free speech. Battles are waging over the role of social media giants like Facebook and Twitter in monitoring conversation and content online; a new phenomenon of "cancel culture" can swiftly drown out countering opinions before they have room to mature or be fully understood; and, of course, we can now easily dismiss facts and perspectives we don't agree with as simply "fake news."

The year 2020 has been unprecedented in countless ways; only time will tell whether the upcoming election will join the fray as one of this year's watersheds. Yet perhaps we can prepare ourselves for the coming onslaught by familiarizing ourselves with the game. Constructing Revolution has shown us how the propaganda of the past is similar to what is being disseminated now. The Art of Massaguer reveals that today's satire is no different than yesterday's. And Radicals and Reactionaries offers a mirror for our current political volatility. With so many echoes between then and now, no single post can cover it all—but at least we are equipped with some tools of interpretation moving forward.