July 16, 2020

By Zoe Welch, Education Manager

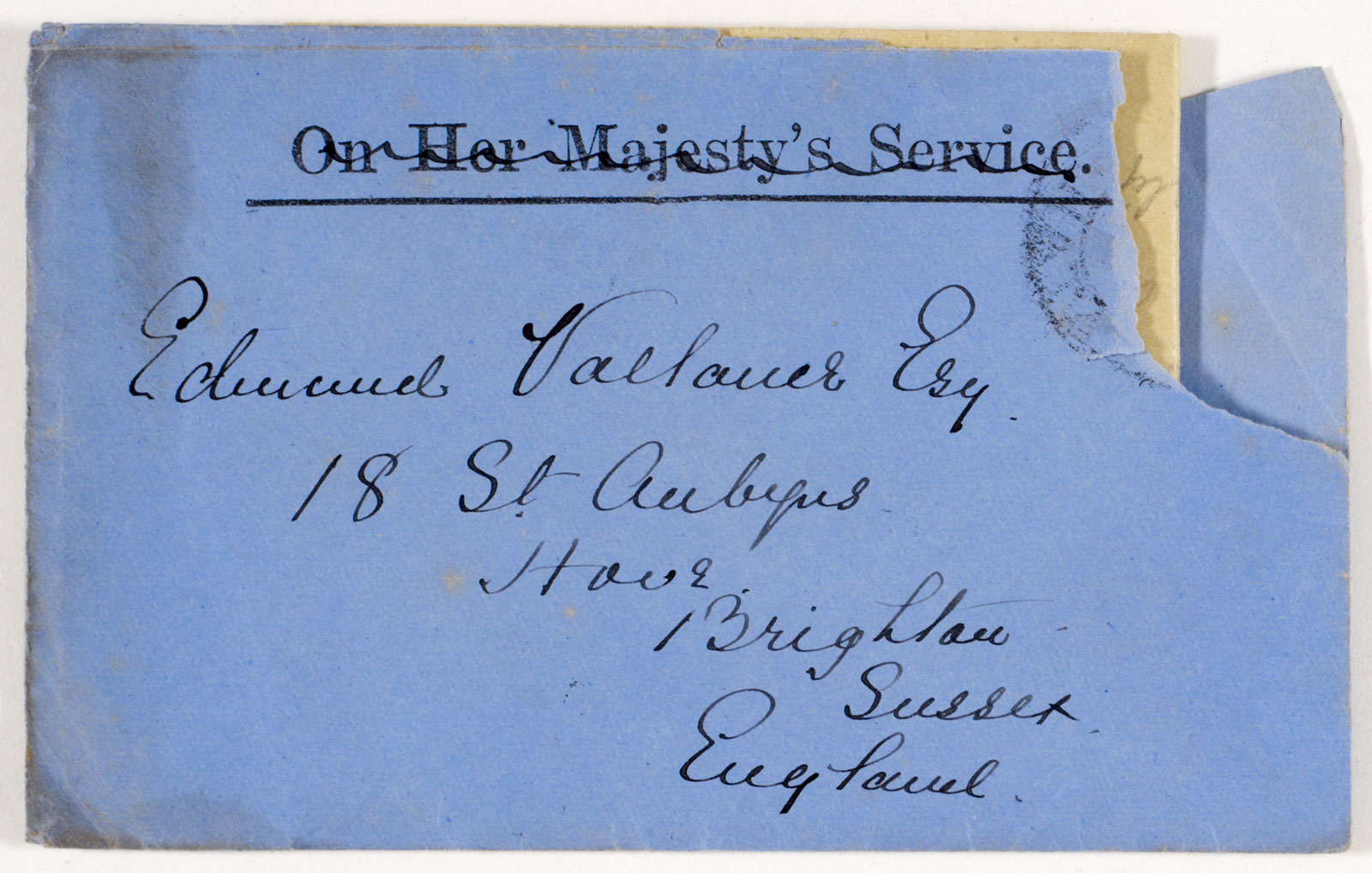

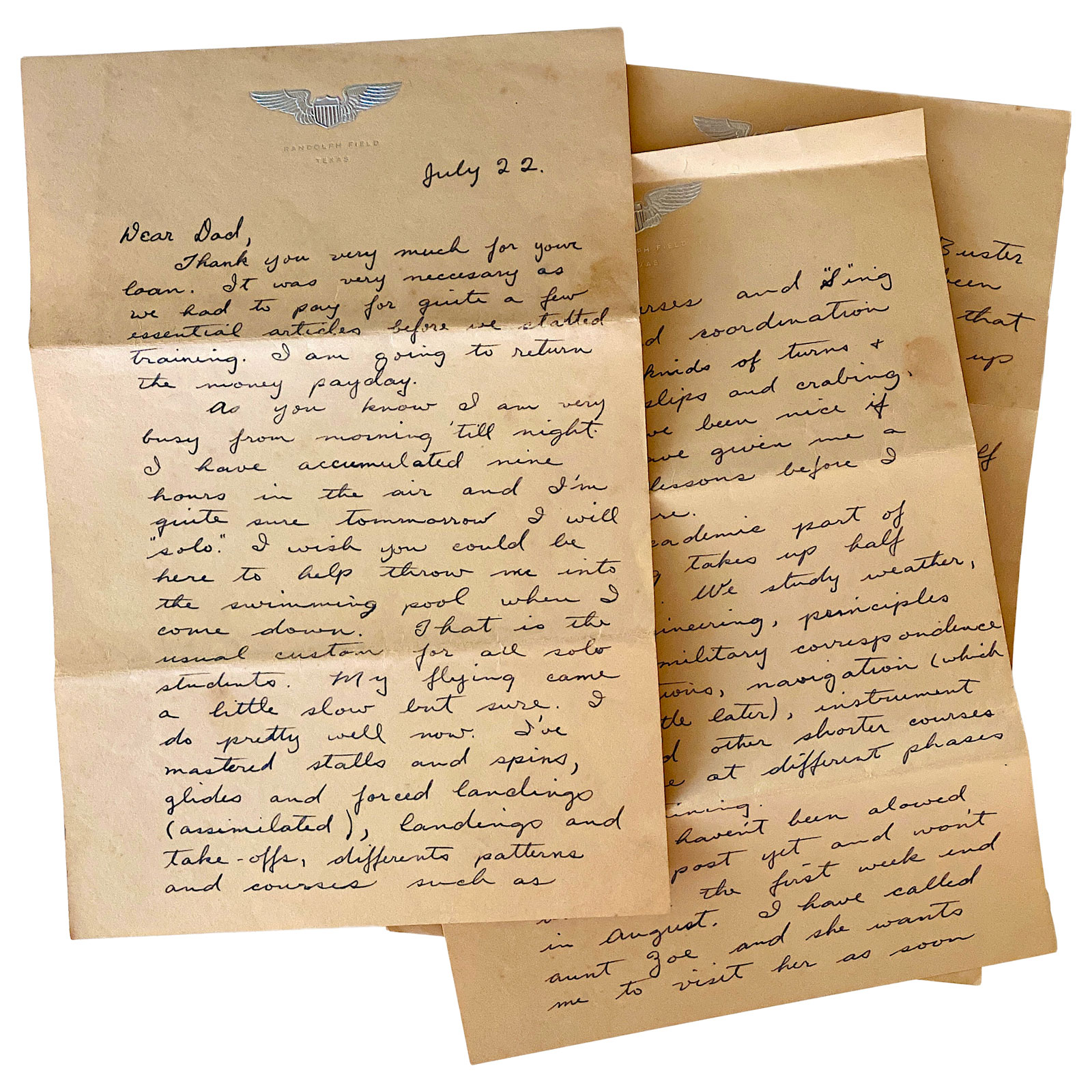

Examine the letter shown in the banner on this page. Don't you want to pick it up, turn the sheet over in your hands, hold it up to the light and see the glow through the page, feel the texture of the ink on the paper? It looks like it's written on onionskin paper—a virtually sheer sheet, its lightness important during the days when airmail (called Par Avion at its inception in London in 1929) was very costly and people economized on postage by using lightweight paper. I don't know if I would be as inclined to handle and explore this letter if it were typewritten, to let it linger in my hands. I might still want to read it as eagerly, but with so much sensorial promise gone, much of the personal would be too.

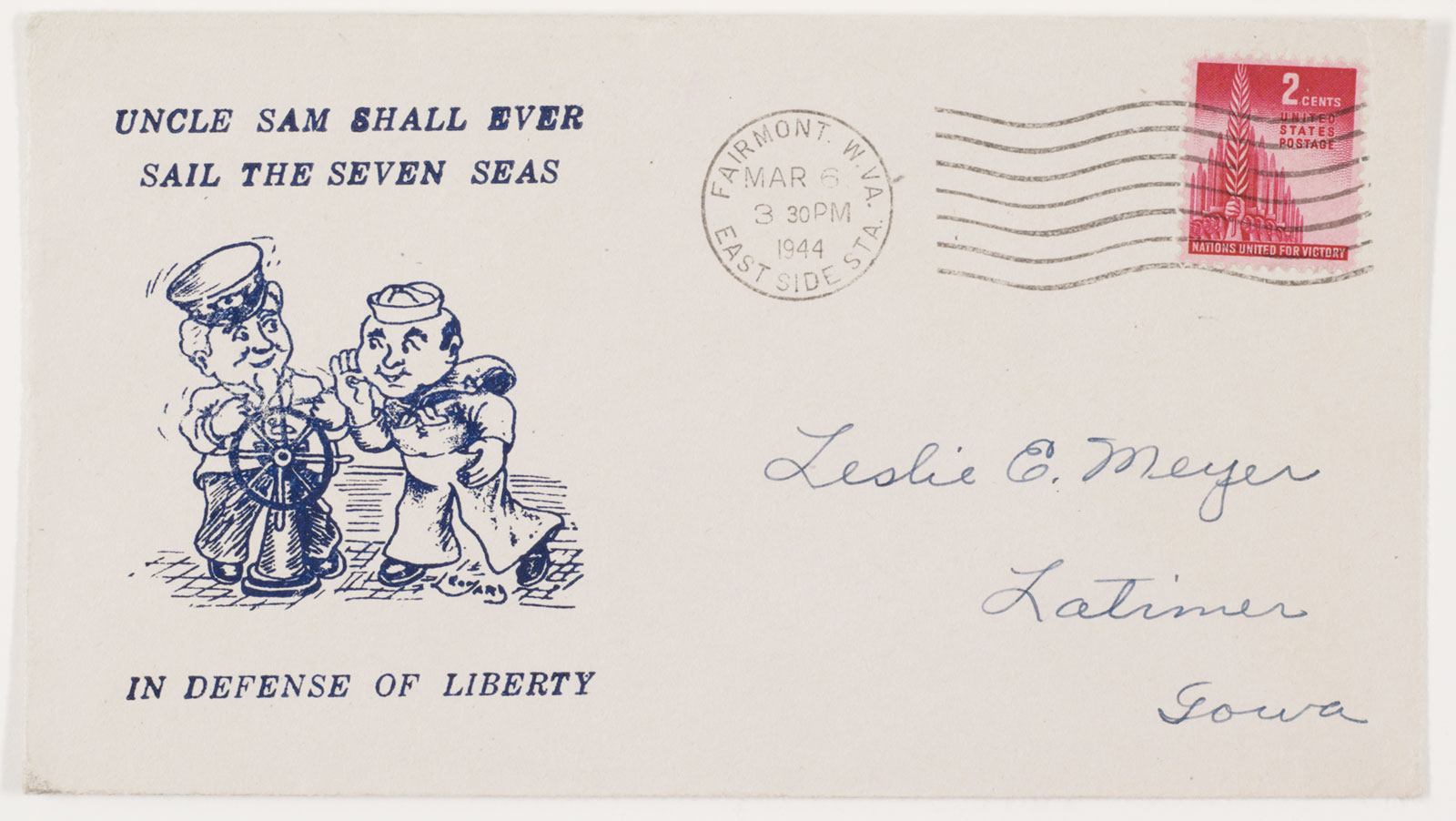

Envelope, 1902. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection, XC2010.08.1.212.

Letter writing gets short shrift these days. It's considered a relic at best, a waste of time at worst, gone from something quintessential to something antiquated—mostly. Retro is currently cool, again: vinyl records; 35mm cameras and Polaroids; rock band t-shirts; high-waisted pants; cocktails and shaker kits; even throwback IG filters. But so far, handwritten letters haven't made the cut, perhaps because they don't contain much to package and sell.

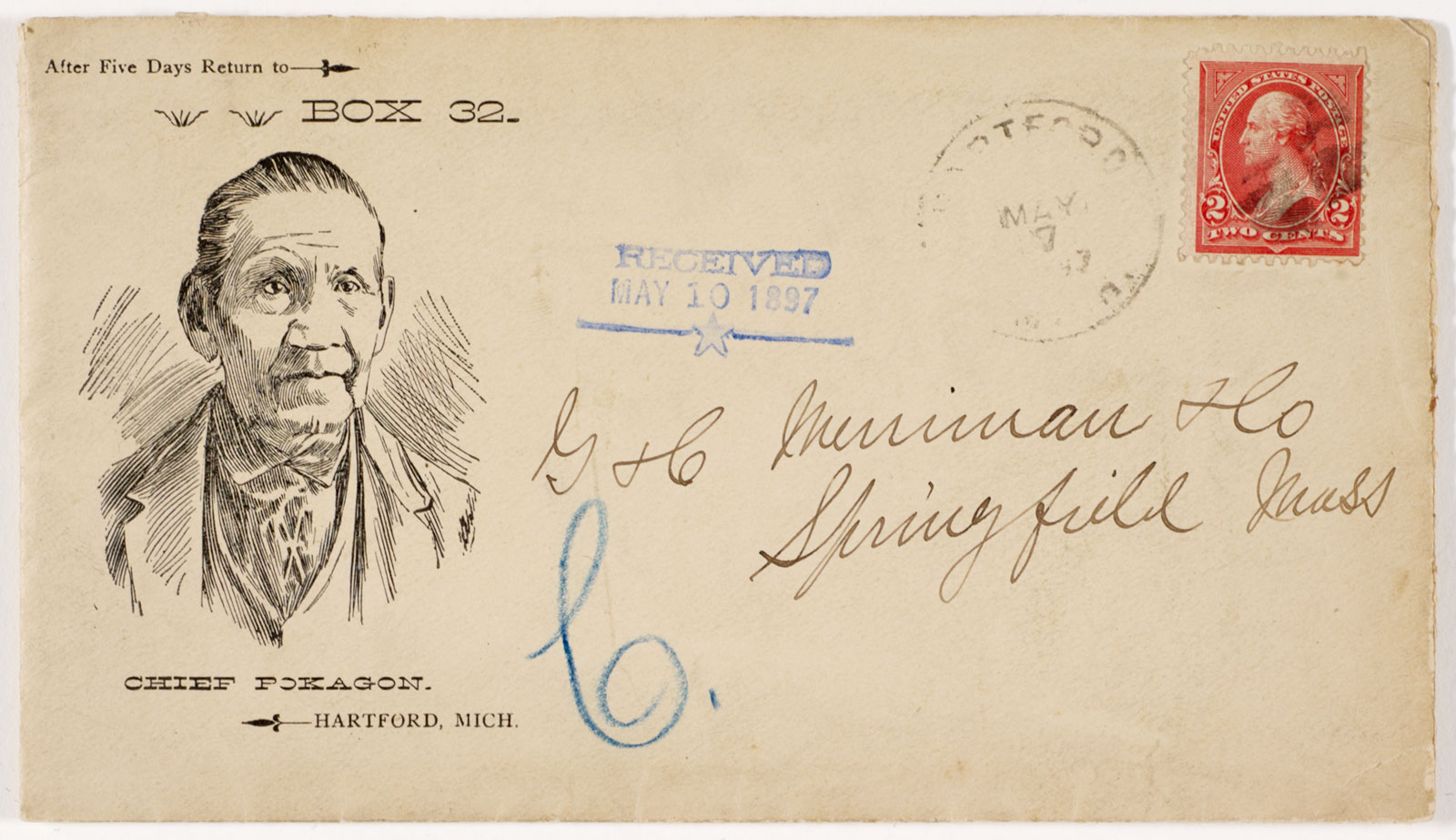

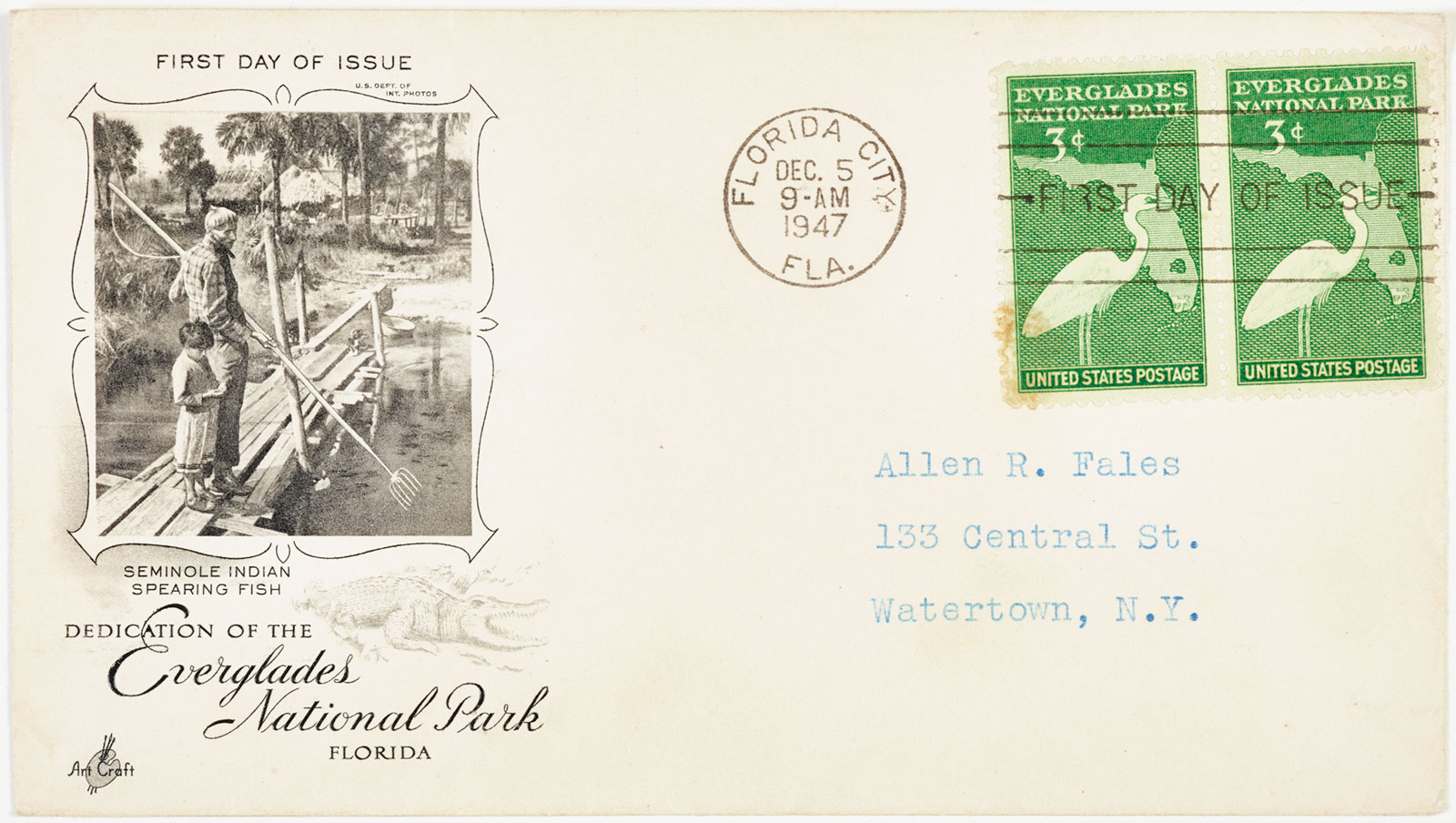

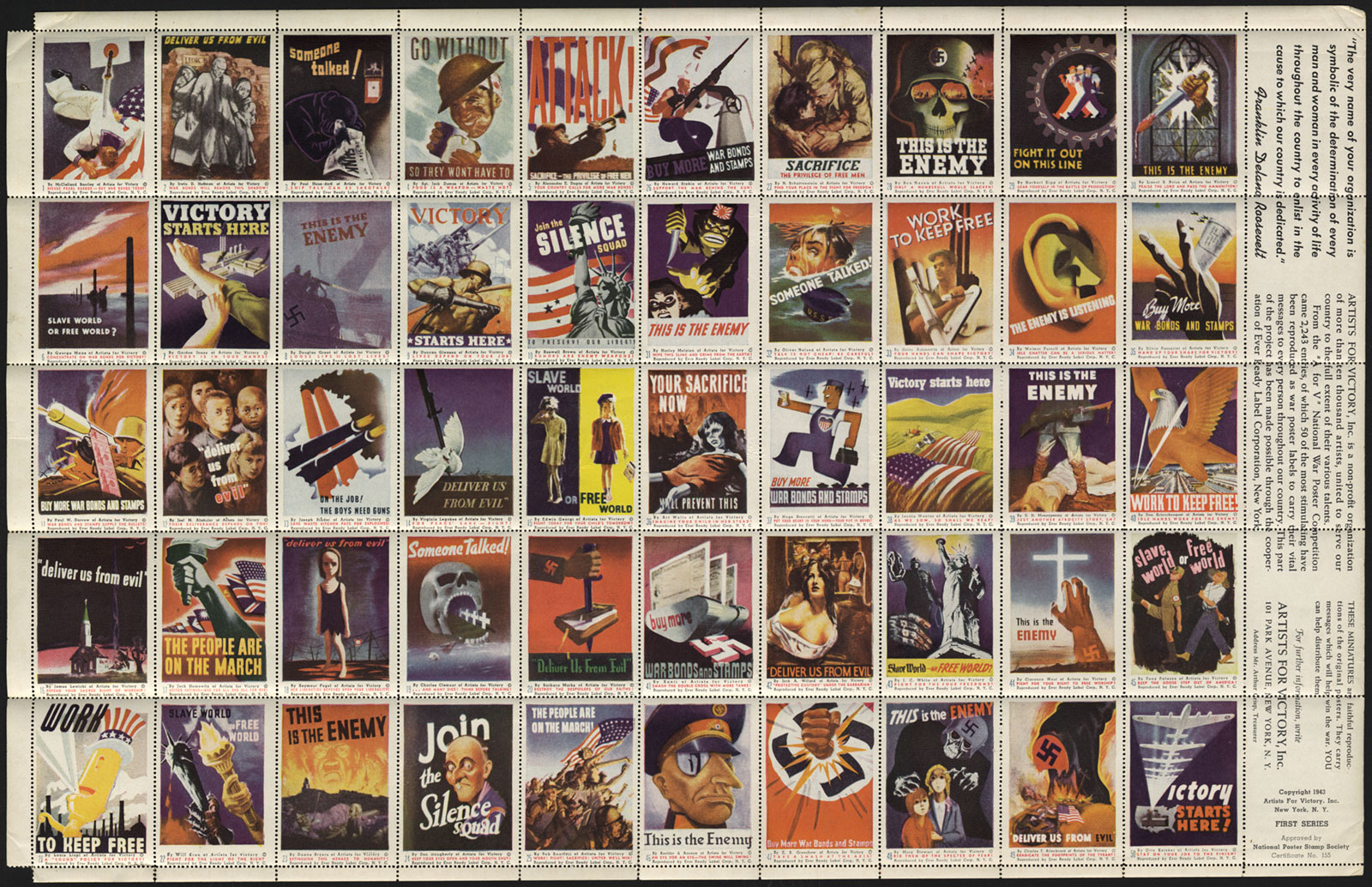

Letters record lives. And the culture around those lives laces the written lines, forming records of public history, capturing and reflecting for us the more intimate portions of collective life as they play out in private spaces. Why else would letters like the one above join collections in public archives, libraries, and museums? If you type "letters" into Harvard library's special collections search engine, and then "image," you get 9,655 hits. If you do the same for the New York Public Library, you get 18,038. The Wolfsonian doesn't have actual letters in anything like these numbers, but we do have plenty of items that document the role of letter writing for past generations—postcards, stamps, envelopes. Sometimes items like these carry the entire personal stories, secret dramas, and innermost thoughts of major historical figures. I've read the collected correspondence between Al Purdy and Margaret Laurence, and between Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz; next on my list is the published collection between Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark as well as the letters of Ernest Hemingway.

I don't just read letters between others, I exchange them too, mine written out in longhand through many years of practice. I wrote my first letters to my parents, first to my father who lived far away as I grew up, and then to my mom when I left home. Our correspondence continued until they each died. Today, the W of my signature is very much like my mother's (a graceful line elongating the arc of the final curve), and I think of her each time I sign something by hand. I always look forward to renewing my stash of stamps, too—like Wolfsonian founder Micky Wolfson, I make my selection based on the artistry and the message, little pieces of art I then send across the world. I maintain long-distance friendships through letters, each peppered with haikus and illustrations for the reader; I've participated in prison pen-pal programs, writing to a mother of three serving life for minor charges under the 1994 three-strikes-you're-out law; I've even fallen in love through letters.

After each of my parents died, I travelled to their cities to handle arrangements and found saved letters in their belongings, some from me, some about me, some simply telling each other about their lives over time. I even found letters other people had written to them. Through it all, I learned more about myself, about them, and about the world around them at the time. There's mention of the founding of Greenpeace, where my mom volunteered, located just around the corner from me on W. 4th in Vancouver; there are neighborly chats between my father, who was in the air force, and Mickey Munday, Miami's Cocaine Cowboy pilot who lived down the street; and there's documentation of my father's pilot training in the early 40s. I still have it all.

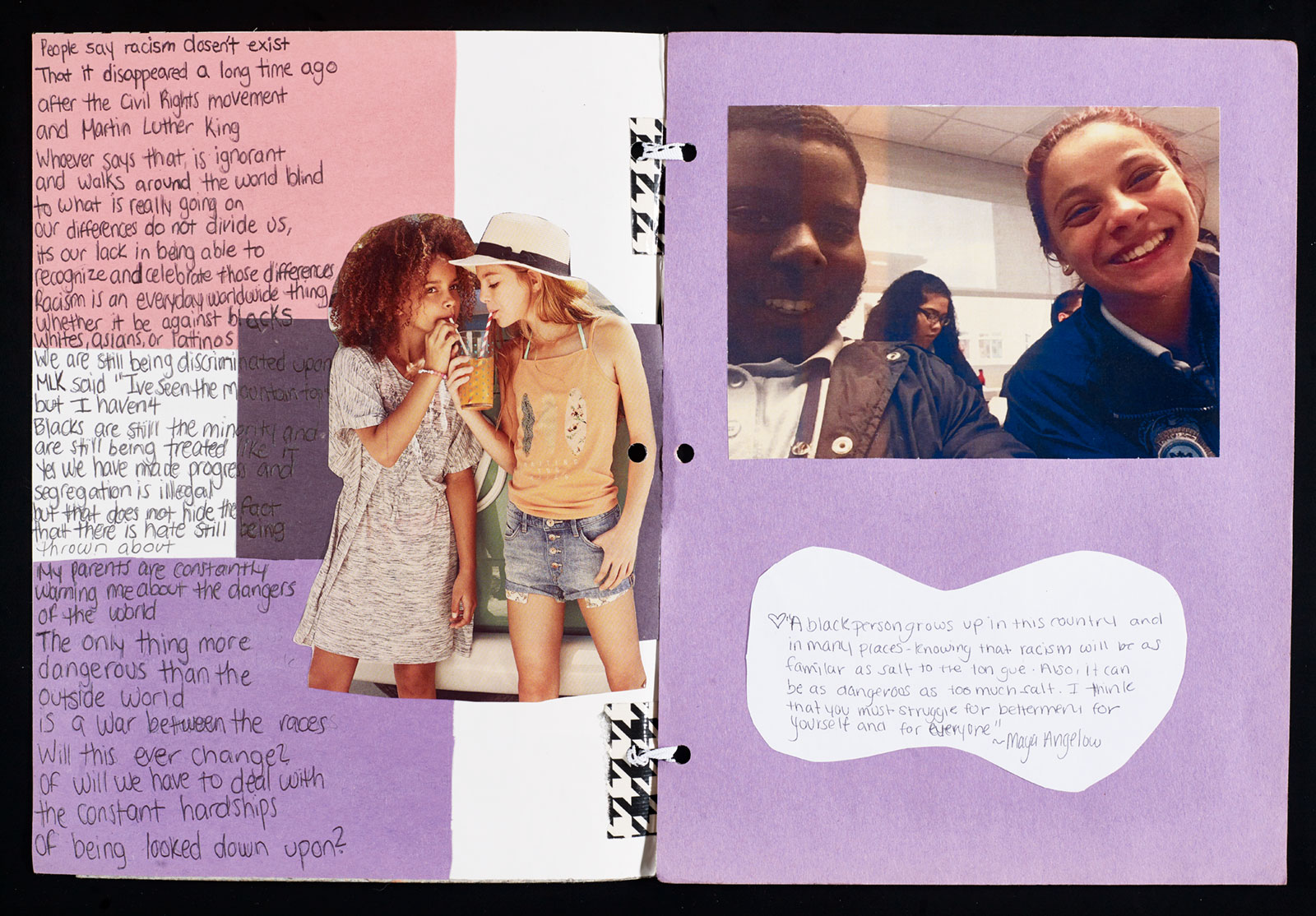

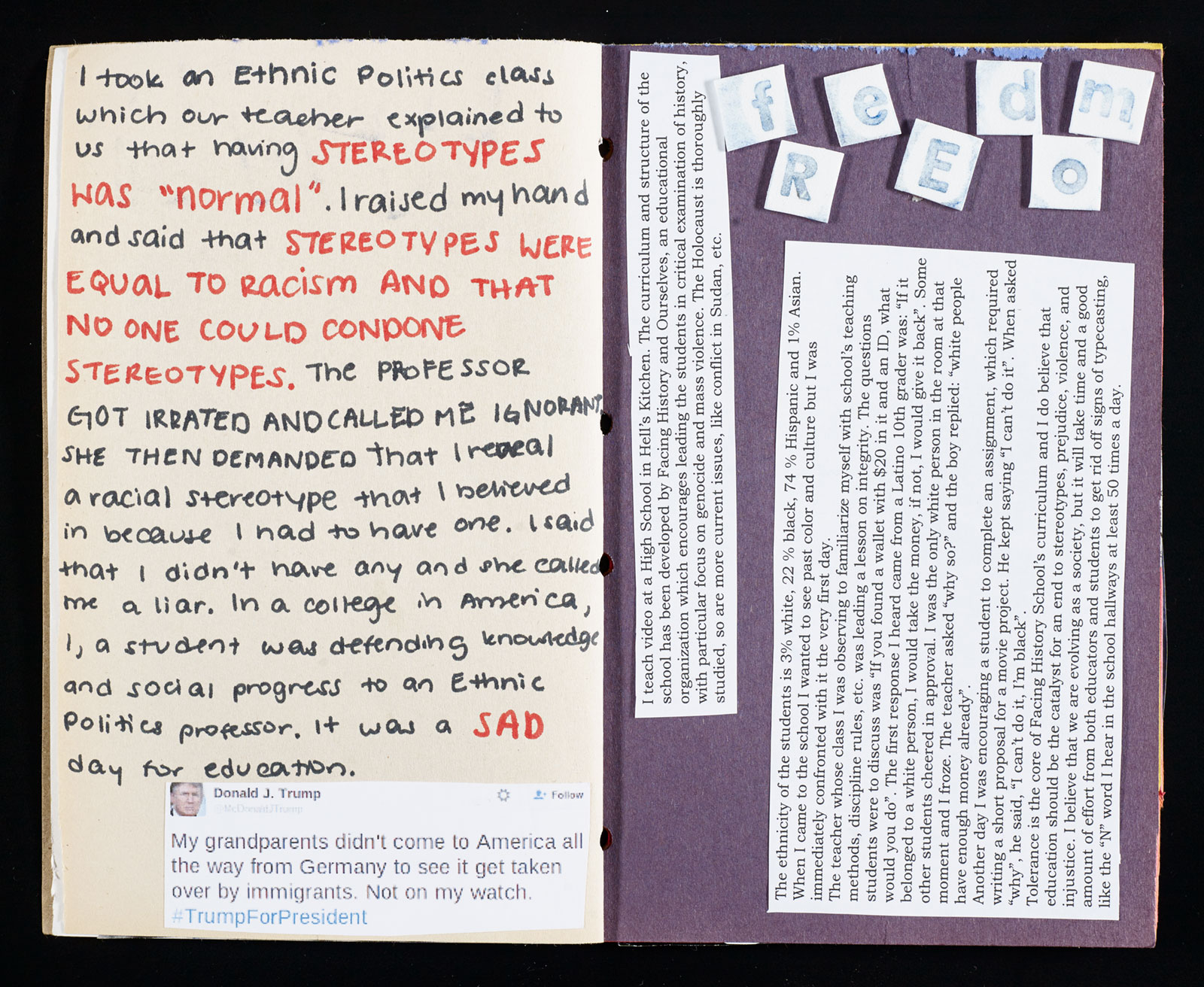

As an educator, I work a lot with senior high school students, and I always make a point of asking them to explore their project ideas with pen and paper. When writing longhand, neural activity is triggered in particular ways—all good for cognition and creating. The field of research known as "haptics," which includes the interactions of touch, hand movements, and brain function, tells us that cursive writing trains the brain to integrate visual and tactile information and helps with fine motor dexterity. It's a spatial, cognitive, and kinetic practice. Other research highlights the hand's unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas, forcing us to rephrase ideas and concepts in our own words, igniting pathways in the brain that go near or through parts that manage emotion, all making learning both stickier and more holistic. It's been interesting to see how many kids, true "digital natives," latch onto the material assignments of our Zines for Progress program, taking great pride in completing something they feel truly reflects who they are, for some their very first school project that involved paper.

I've often wondered about those who don't write by hand or correspond by letter anymore. There's a heap of research on how attention is affected by our digital landscape. It turns out that deep reading—the process of thoughtful, deliberate review and understanding of a text—is compromised when we read on a screen. If we skim and scan a lot, surfing from hyperlink to hyperlink, our brains get good at skimming and scanning and surfing and less good at neurological deep diving, the kind of brain capacity required for concentration, contemplation, and reflection. When we spend hours online, we are remaking ourselves in the image of the internet; the medium is indeed the message.

These days, COVID has changed how we live in so many ways, including inspiring a resurgence of letter writing. Texans and Virginians are organizing to get letters to the elderly, and two teenage sisters in Boston started Letters Against Isolation, which has now sent more than 21,756 cards to care centers across the country. Writing-related stories and snail-mail efforts abound: letters by Baltimore kids are being copied and sent to hospital staff and patients; submissions for Oregon Humanities' 6-year-long Dear Stranger letter-writing project have doubled; Operation Gratitude has partnered with the Starbucks Foundation to send letters to frontline responders; and a 5th-grader in Sioux Falls, already an active letter writer, left one in her postbox for her mailman, telling him: "The reason you are very important in my life is because I don't have a phone so how else am I supposed to stay in touch with my friends? You make it possible!"

On a national level, the Irish Postal Service has launched a campaign designed to encourage people to stay in touch with one another during lockdown. Every household across the country has received two postcards that can be mailed out again for free. As a result, 5 million postcards have been created for the campaign.

So, maybe letter writers aren't so out of touch after all. To spread a little love and make meaningful connections, try your hand at it—write someone a letter.

P.S. To help you enjoy the practice of deep reading, I asked that the hyperlinks be inserted at the end, instead of embedded within the body of this writing, and I was granted my wish. Here they are:

Margaret Laurence - Al Purdy: A friendship in letters : selected correspondence

My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: Volume One, 1915–1933

Two Prospectors: The Letters of Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark (Southwestern Writers Collection)

The Letters of Earnest Hemingway, Volume I

Letters Against Isolation (follow them on IG)

Dear Stranger

Operation Gratitude