May 29, 2020

By Silvia Barisione, Senior Curator

More than two months have passed since we closed the museum and began working from home. This physical separation from the objects and galleries is a strange and jarring adjustment. The artworks that I work with every day are shuttered from view, and many of the resources vital to curatorial research are beyond my reach. I am also missing the Wolfsonian building itself, a historic structure that has collection pieces woven into its very fabric, in some cases objects saved by Micky Wolfson from demolition. Two such examples can be found on our striking 7th floor: a painted ceiling and a pair of automobile-inspired chandeliers.

These particular works come to mind as we close out May, which marks National Preservation Month (originally Preservation Week), a celebration of the widespread historic heritage of the United States. It was during National Preservation Week in 1983, paradoxically, that Miami witnessed the demolition of the Ryan Motor Building, a landmark building once located on 2nd Avenue along the banks of the Miami River—and the first home of those chandeliers and ceiling.

The 1926 building was originally the main headquarters of the S.A. Ryan Motor Company, founded by Stephen A. Ryan from Detroit. Ryan moved to Miami in 1921 and successfully took over Flagler Street's Miami Ford Agency, which The Miami Tribune hailed in 1924 as ". . . the most aristocratic of show rooms" where the customer service was so extraordinary, it made ". . . buying a Ford like a visit to Tiffany's."[1] Sales were so successful that the company was forced to find larger facilities after a few years to remain competitive in Miami's rapidly developing market. In 1925, The Miami News announced the construction of the new headquarters as ". . . the largest and finest automobile sale and service building in the world," while reaffirming the "excellent service, courteous treatment, and equitable dealings"[2] of the company.

A new location was chosen along the Miami River with docking facilities for loading cars directly from steamships. Robert Law Weed,[3] one of the young promising architects in Miami at the time, was charged with the project for the new showroom and garage. In the Ryan Motor Building, Weed combined his Beaux-Arts legacy with a more functional and streamlined language, which he would embrace later through influence from Art Deco. Adapting to the site's limitations, the building presented a curving front façade, which was marked by eight gigantic Tuscan columns. This monumental two-story stone colonnade contrasted with the plain plaster wall of the third and last floor defined by a regular row of windows. In the pursuit of a "modernized classicism," Weed used classical elements—the arcade and the triangular pediment above the main entrance—but he simplified the lines in the rounded profile of the front and in the flat rooftop. The round bronze bands around the columns, the wrought-iron lighting fixtures, the steel framed bay-windows, and the alternate use of terracotta, marble, and terrazzo[4] floors skillfully combined new and old materials and techniques to produce a remarkable building with great attention to detail and craftsmanship.

The new headquarters attracted thousands of visitors when it was opened, as The Miami Herald reported several years later in 1934:

"…each year many tourists visit the structure to admire the architecture. Much interest is shown in the display room where Italian and Pompeian architecture are blended to create a setting in harmony with the semitropical surroundings and climate."[5]

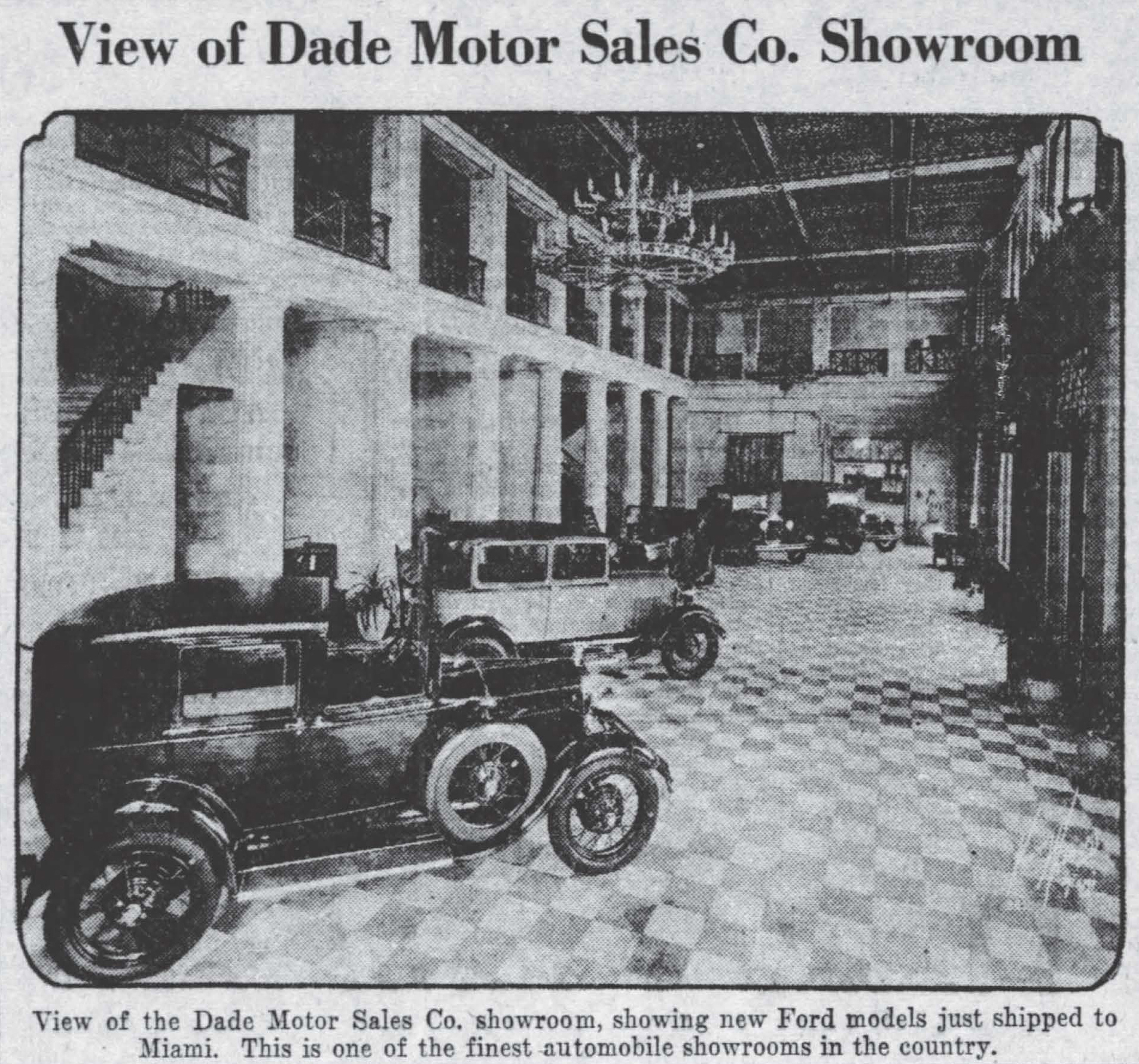

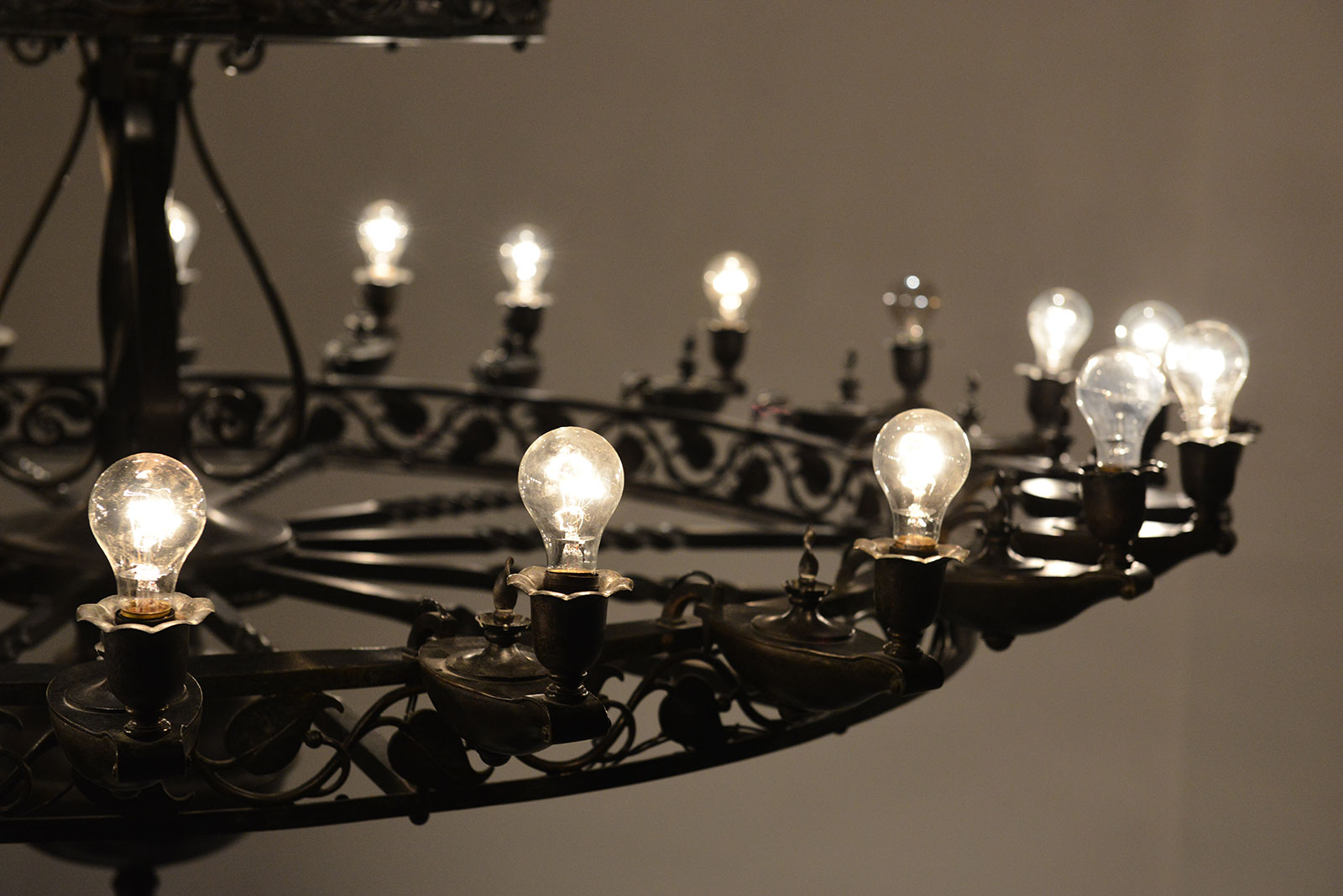

Inside the showroom, a row of Doric columns divided the two-story open space featuring travertine walls, "a floor of Tavernelle and Georgia marble,"[6] and a polychrome ceiling which referenced the so-called Mediterranean Revival, the style popularized in South Florida in the 1920s in accordance with Florida's legendary Spanish colonial heritage and climate. Looking attentively at the coffered wood ceiling and at the two wrought iron and brass chandeliers, customers could see that the traditional decorative pattern was interweaved with the depiction of stylized car parts—tires, steering wheels, and industrial gears—merging the elaborate ornamentation and craftsmanship of the Spanish Colonial revival style with a machine age iconography (also evident in the wheel-shaped chandeliers).

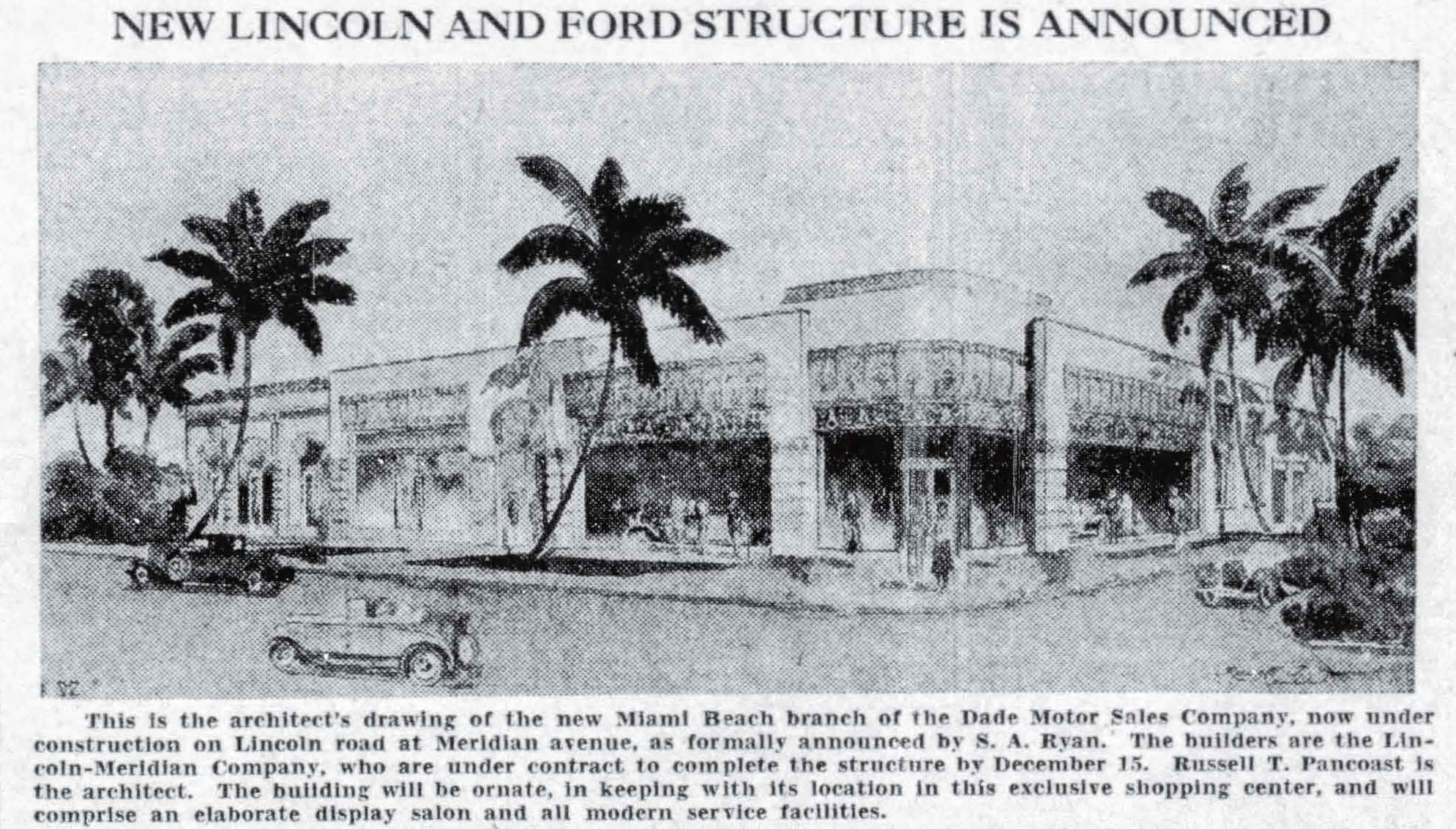

There is not much photographic documentation left about these interior pieces in their original setting. Larry Wiggins, The Wolfsonian's accountant as well as a Miami historian, author, and postcard collector, found a very rare image of the showroom published in 1929 in The Miami Tribune.[7] Thanks to his research, we also now know that S.A. Ryan opened a branch in Miami Beach at the end of that same year. Evidence shows that while the rest of the country was affected by the Great Depression, Ryan's company was growing and opening new service and salon branches under the corporate name of Dade Motor Sales. At the time, The Miami Herald publicized the new structure ". . . of very beautiful modernistic design, with ornamental stone and wrought iron treatment in the façade . . . one of the outstanding buildings along Lincoln Road."[8] Located at the corner of Meridian Avenue, the Miami Beach showroom was designed by Russel T. Pancoast[9] and reflected the same Art Deco aesthetic Pancoast adopted one year later in the Collins Memorial Library (now The Bass), widely but wrongly considered to be the first Art Deco building in Miami Beach. In both Ryan Motor projects—the Miami River headquarters and Lincoln Road outpost—the choice of architects denoted Ryan's refined taste, which evolved toward the more geometric and modern in Pancoast's commission.

The Ryan Motor Building on the Miami River was sold in 1937 and later acquired by the Florida Power and Light (FPL) Company, which remodeled it in the 1950s. After 1980 it became vacant, and FPL ultimately decided to destroy it to make space for their new headquarters. "It was listed as a landmark during a 1978 Metro Survey of Dade's historic sites"[10] lamented The Miami Herald, denouncing the demolition in 1983. The City of Miami Historic Conservation Board officials had been planning to designate the building as historic at the city board's next meeting. The designation ". . . would have protected it at least temporarily from the wrecking ball," regretted the article.

Though the building no longer exists, members of the Dade Heritage Trust were able to save at least some of the architectural elements and gave them to Micky Wolfson, collector and preservationist par excellence,[11] who stored them and later incorporated them into The Wolfsonian–FIU.[12] While the wrought iron railings are still in storage, the architect Mark Hampton, in charge of The Wolfsonian's project, used some of the bronze bands decorating the exterior stone columns to design three unique table bases, and integrated two brass doors in the Wolfsonian offices. Finally, he installed the painted ceiling and chandeliers in the museum’s grand two-story galleries, matching perfectly with the Mediterranean Revival style of the 1927 building, originally the Washington Storage Company.

I intend to make these unusual and fascinating collection pieces one of my first stops when we're able to return to The Wolfsonian and I invite you to come and have a taste of the lost magnificence of the Ryan Motor showroom when we reopen.

[1] "Oldest Ford Dealer is now the largest", The Miami Tribune, Sunday, November 30, 1924.

[2] "Ryan Company Building Home", The Miami News, Saturday, October 31, 1925.

[3] Robert Law Weed (1897–1961) was born in Sewickley, Pennsylvania and attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. Weed moved to Miami in 1919 to work with Kienhel & Elliott and opened his own practice in 1922. Between 1925 and 1927 he participated in the planning of Coral Gables building the Italian Village with architects Alfred L. Klingbeil, John and Coulton Skinner, and R. F. Ware. One of his first Art Deco projects in Miami is the Shrine Building, also known as Boulevard Shops, at 1401–1417 Biscayne Boulevard.

[4] Terrazzo flooring usually consists of marble or granite chips set in concrete.

[5] "Dade Motor Sales Celebrates Record", The Miami Herald, Wednesday, September 12, 1934.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] "View of Dade Motor Sales Co. Showroom", The Miami Tribune, Sunday, May 19, 1929.

[8] "Motor firm building Miami Beach Branch", The Miami Herald, Sunday, October 6, 1929.

[9] Russel T. Pancoast (1898–1972) was the architect, the Lincoln-Meridian Company were the builders. Pancoast, the grandson of John S. Collins, had studied architecture at Cornell and, like Weed, in his early years he worked in the Miami office of Pittsburgh architecture firm Kiehnel & Elliot. His first big commission was the Surf Club in Surfside in 1929.

[10] Rick Hirsch, "FPL Levels Downtown Landmark", The Miami Herald, Wednesday, May 13, 1983.

[11] Wolfson has also been one of the founding members of Miami Design Preservation League.

[12] In particular "Veteran Preservationist Don Slesnick", see "A Requiem for Some Heavyweights That Have Tussled with The Wrecking Ball and Lost. Dade's Greatest Hits", New Times, July 27–August 2, 1995. I thank Casey M. Piket and Christine Rupp for providing the image from Dade Heritage Trust Preservation Today magazine.