May 8, 2020

By Alexandra O'Neale, Membership + Events Manager

Lana Del Rey. Rihanna. John Legend.

If you love music—you're human, aren't you?!—right now you might be spending more time than normal with these familiar voices. I've been thinking a lot about music's role in our lives as artists like Thundercat, Fiona Apple, and Adele provide the soundtrack to my work-from-home experience. We talk about music as a comfort, an escape, a means of release, or a source of energy, phraseology that is near-spiritual and ascribes a sort of magical aura. Songs can resonate in deeply personal ways (i.e. mixtapes), but they can also connect people across cultures, generations, classes, and time (Beyoncé is close to a religion, after all).

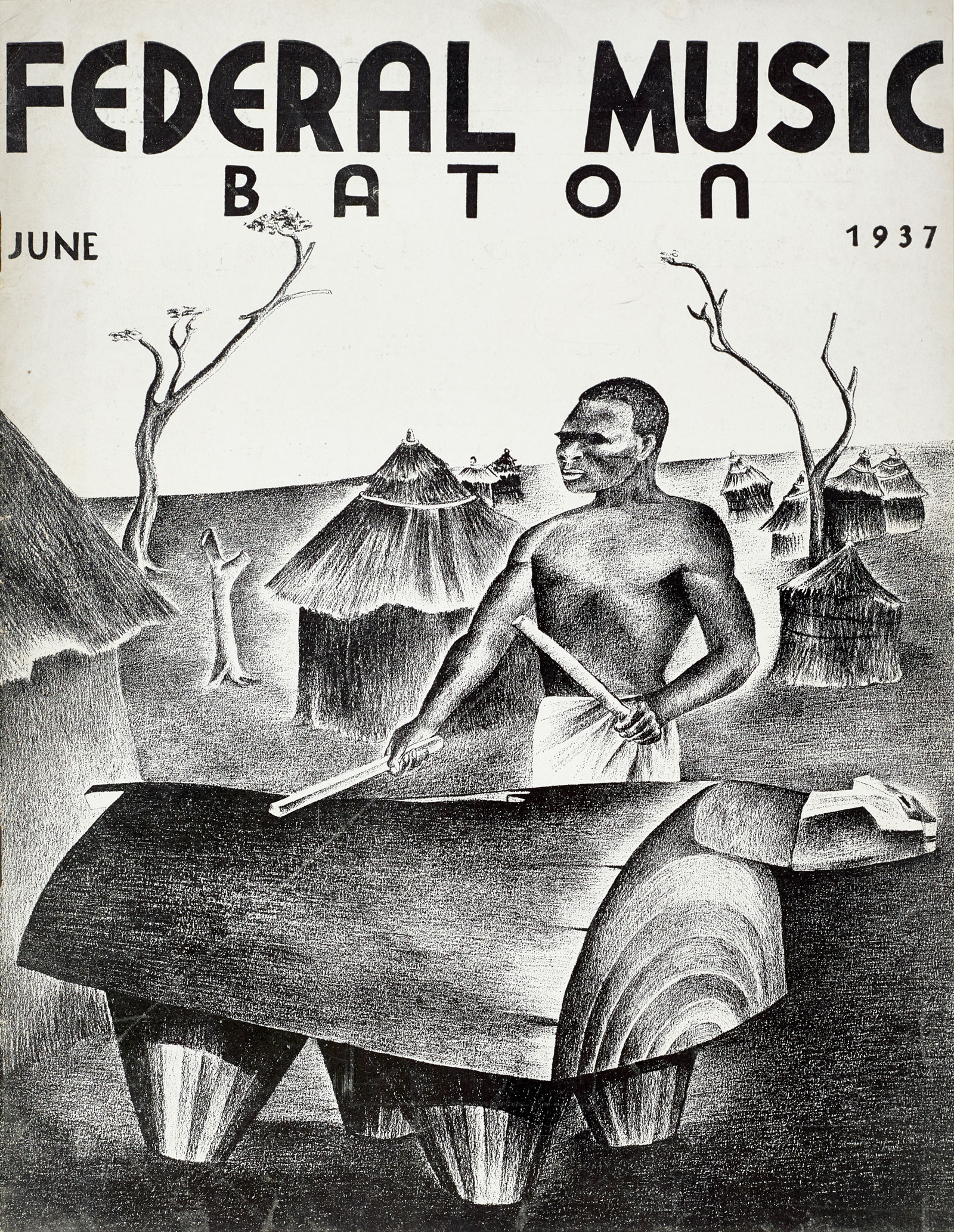

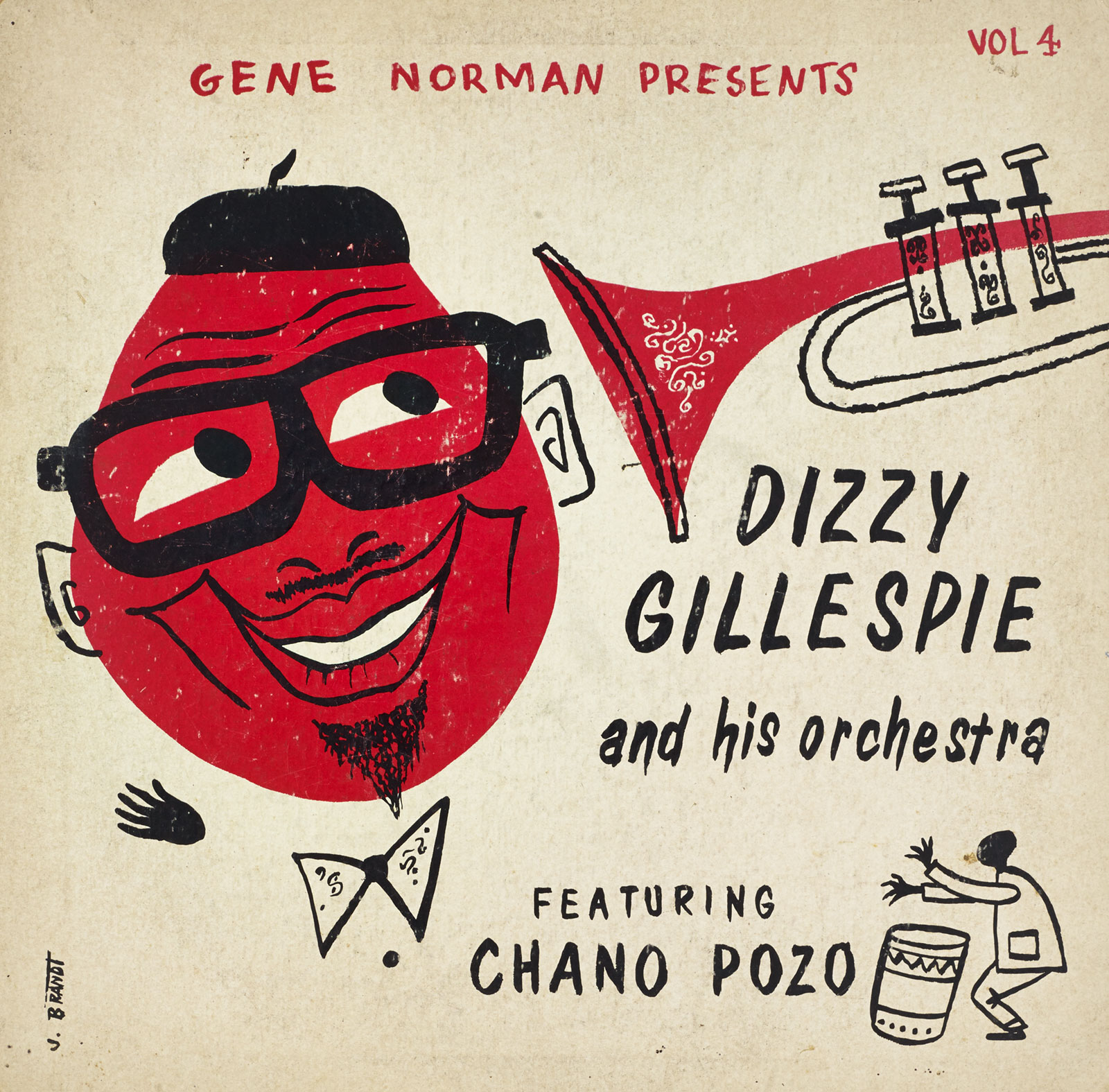

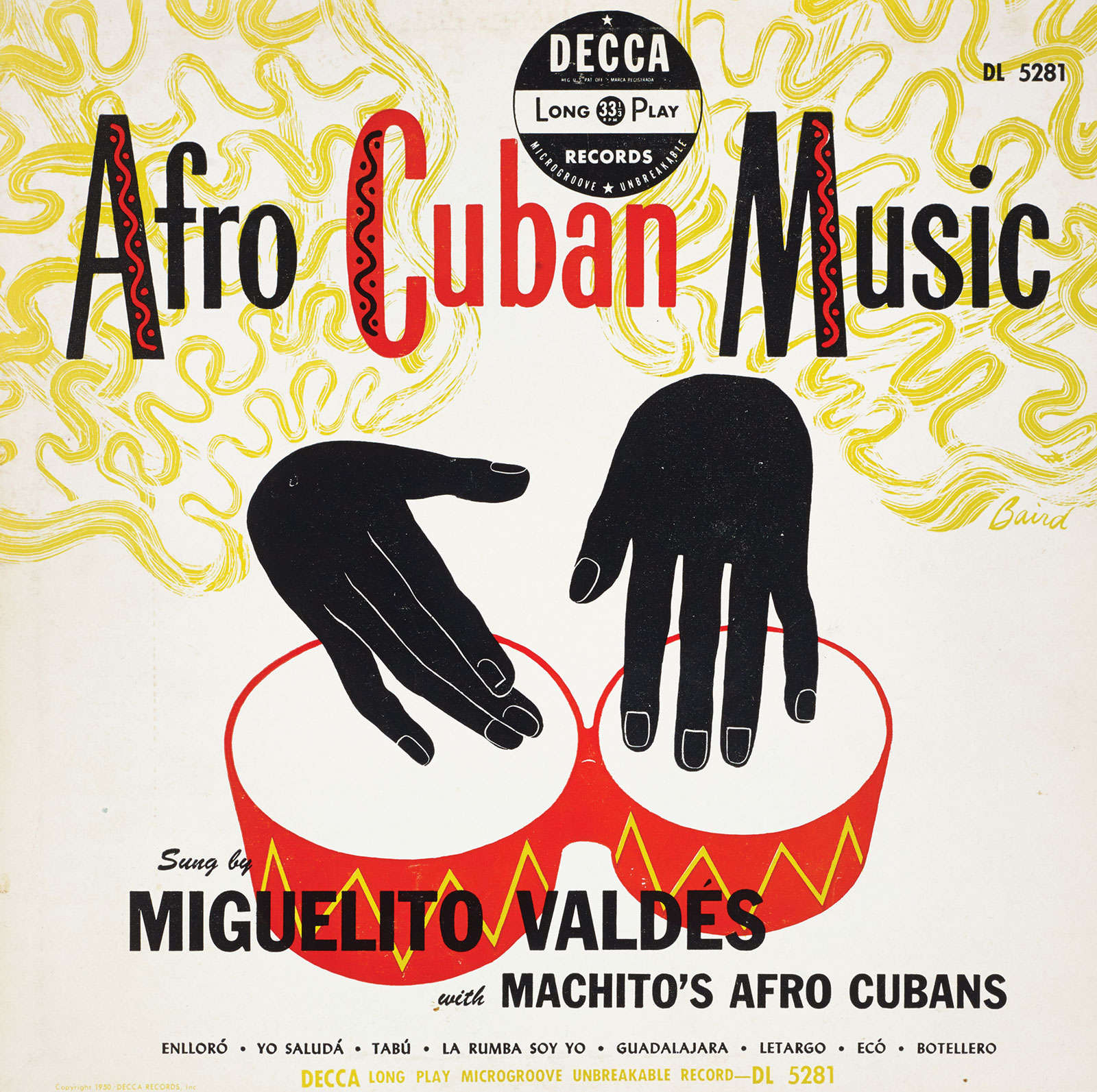

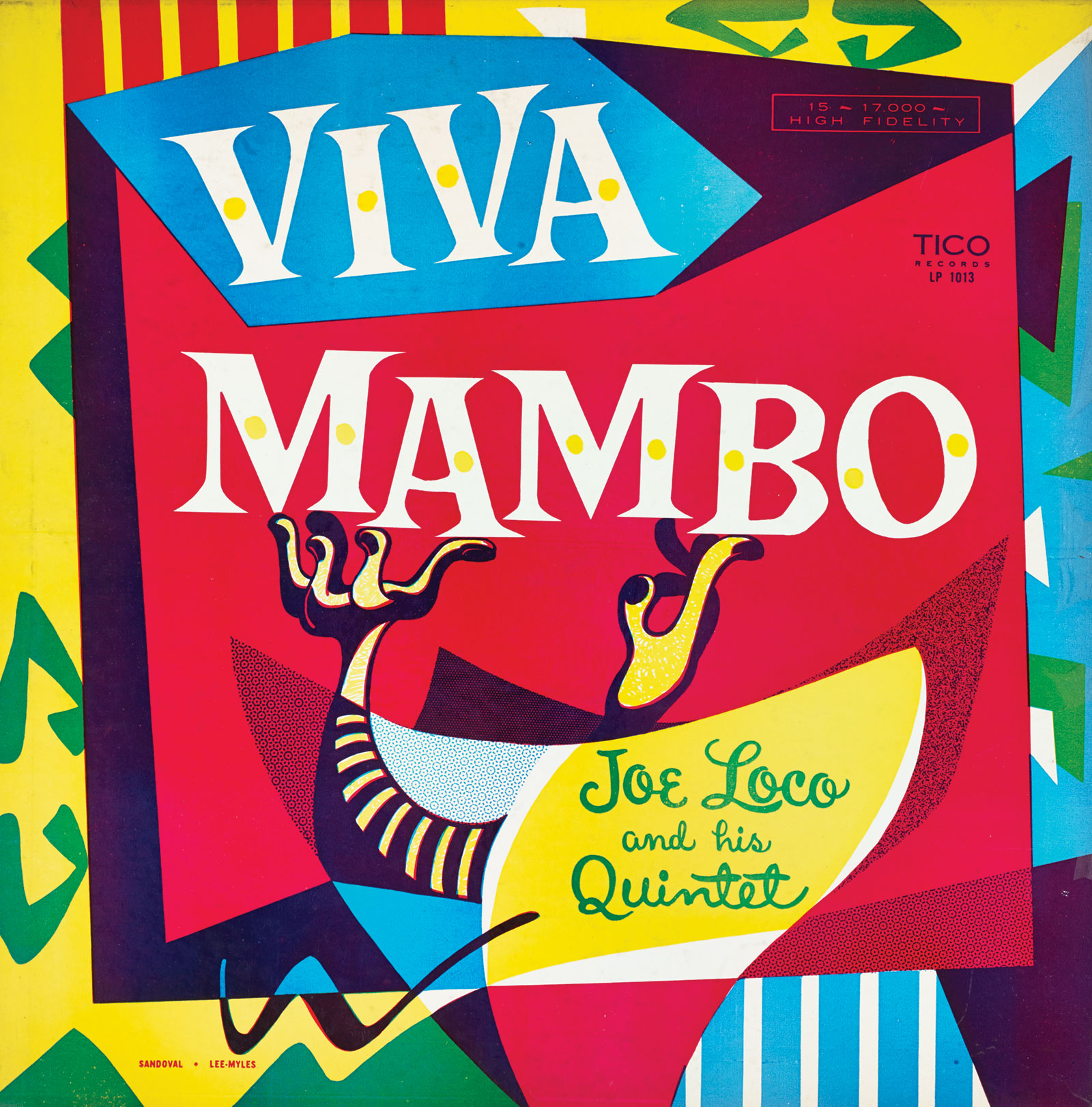

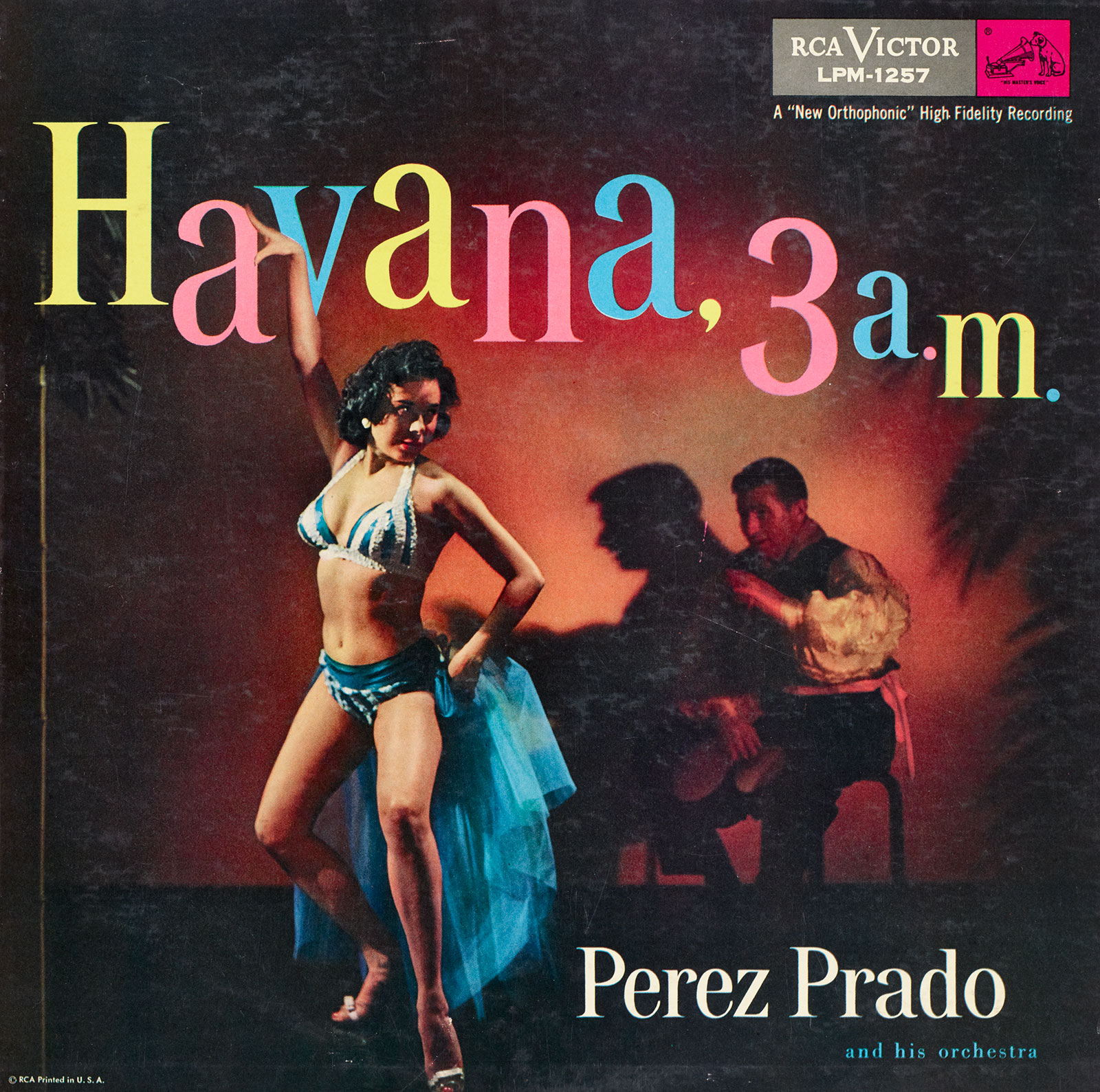

But even when I'm lost in the moment, jamming out to my favorite singers or bands, I'm struck by contemporary music's historical roots. I'm sure that part of that comes from my work at The Wolf, a museum that focuses in on the many hidden ways the past influences the present, a theme we've teased out specifically through the lens of music in several recent programs like The Wolf on Wax. Through those events, I became more acquainted with the institution's intriguing music holdings, which include substantial collections of sheet music, phonographs, and even vintage records. Much of the artwork shown throughout this post represents one of our strengths, modernist album covers, which have been popping into my mind lately as a sort of visual backdrop for my latest auditory obsession: Afro-Cuban jazz.

Clues about the genre's lasting power have been bubbling up in my listening sessions. Certain rhythms arise again and again in today's Top 40, but it took me a while to recognize them as echoes of old-school hits. The synergies weren't necessarily hidden, but they were steadily beating just below my perception level, like a bassline you at first don't notice but then can't unhear. Armed with earworms and melodies, I decided to uncover how it all relates—cue my evidence board and red thread!

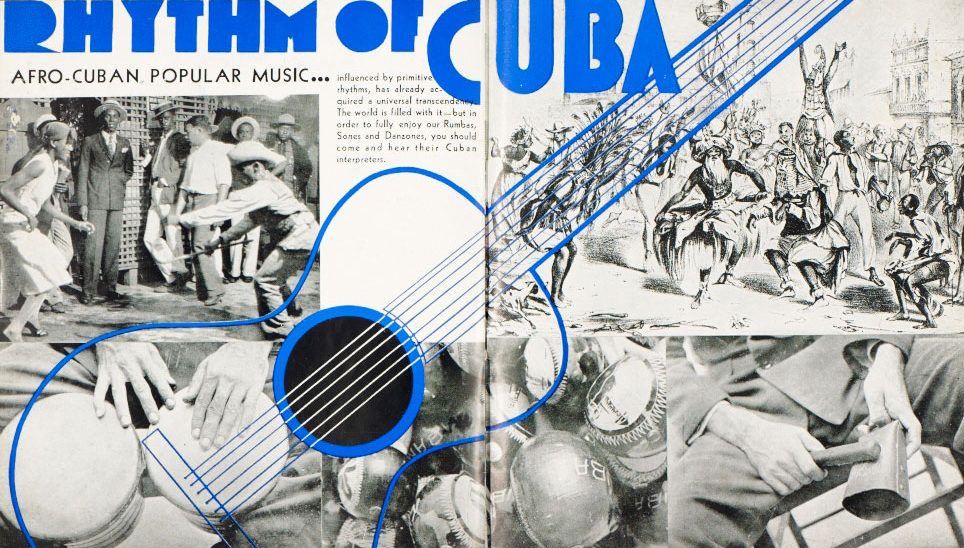

One of the earliest and most popular forms of Latin jazz, Afro-Cuban jazz is a unique blend of clave-based rhythms and harmonies that reflect Cuba's diverse and vibrant history. Before this genre was banging on the walls of famous clubs during the height of New York's jazz scene (the 1920s–40s), its origins trace back to the Atlantic slave trade and sugar plantations in the Caribbean, Louisiana, and Brazil.

Plantations in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) produced 40% of the world's sugar before the slaves rose up in the first successful slave revolt in the Western Hemisphere. In the wake of the Haitian Revolution, thousands of French colonists fled the bloodshed and chaos, seeking refuge and opportunity especially in eastern Cuba and Louisiana, where sugarcane production would eventually rise and eclipse that of Haiti.

The slave trade continued to bring slaves to Cuban shores long after it ceased adding slaves to the North American mainland, creating a surge of people of African heritage on the island. Slave masters in the United States and Cuba generally held different views about the wisdom of permitting slaves to play and create music; in most U.S. territories, drumming was prohibited for fear that slaves might use drumbeats to transmit plans and messages of uprisings. Cuban slaves, on the other hand, were permitted to play drums and the clave, a hardwood percussion instrument which was used to produce a five-beat pattern that later became the structural foundation of Afro-Cuban jazz. Drawing from the slaves' strong connection to African drumming traditions and polyrhythmic roots, Cuban musicians mixed this influence with Spanish music to create an entirely new musical genre.

In the 20th century, musicians from the ports of Havana and New Orleans ferried back and forth between the two cities to perform, resulting in the sharing and blending of musical influences. Jelly Roll Morton, an American jazz pianist from New Orleans, acknowledged the contributions Cuban musicians had made to the city's sound when he referred to habanera rhythms as "Spanish Tinge," a component vital to "real good jazz." He would later incorporate it into some of his own songs, for example "New Orleans Blues" and "The Crave."

But most music historians trace the true birth of Afro-Cuban jazz to trumpeter Mario Bauzá. Bauzá would play an influential role in bringing Cuban music to the New York jazz scene, and he was the first to blend jazz with clave in his 1943 hit "Tanga," largely considered the first Afro-Cuban jazz song. While he was a musical director for drummer and band leader Chick Webb, Bauzá met bepop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie and introduced him to Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo, creating a chain of relationships and stylistic influence that forever changed the landscape of Latin jazz.

Photograph of Silvestre Mendez, musician Miguelito Valdés, and percussionist and composer Chano Pozo, c. 1943. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Vicki Gold Levi Collection, XC2016.01.1.47.

Pozo and Gillespie co-wrote several famous Latin jazz numbers, such as "Manteca" and "Tin Tin Deo." Bauzá's brother-in-law, Machito, would also help lay the groundwork for the genre through his Latin jazz band, the Afro-Cubans, who often collaborated with jazz greats (Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich) and were known for their blend of Cuban melodies with American swing influence. The band's popularity increased dramatically in the 1950s, when there was a frenzy for mambo in the U.S.

This blend of African-American and Afro-Cuban musical traditions was made possible through the pre-1959 ease of travel between the U.S. and the island nation. Not only did American and Cuban musicians regularly shuttle back and forth between Havana, New Orleans, and New York, shaping each other's work and practice directly, but American tourists visiting trendy honeymoon and vacation spots also returned stateside with newfound love for the musical traditions of Cuban entertainers.

Album cover, Machito at the Palladium, 1960. The Wolfsonian–FIU, XC2016.01.1.1353.

The genre took off from there. From New York to Miami, Americans danced to Afro-Cuban jazz and mambo at clubs and flocked to record stores to buy up sound recordings for home entertainment.

I mentioned the backbone of Afro-Cuban jazz, the clave. The most favored clave rhythm is the son clave, a 3-2 or 2-3 pattern. While the clave was at the center of mid-century genres like the mambo, rumba, and salsa, its beat would continue to pop up as music evolved. In 1955, blues guitarist and singer Bo Diddley's self-titled song used the son clave 3-2 rhythm. We also see this crossover in The Beatles' 1964 hit "And I Love Her," with Ringo swapping the drums for bongos and claves.

Another frequent clave rhythm in Cuban music is the tresillo, a Spanish word meaning "triplet," since three of the same notes are successively played in the timespan normally occupied by two. We also continue to hear clave rhythm in music with island origins, such as dancehall and reggaeton, before it makes its way into the spectrum of contemporary pop, from dance to R&B. Listen to Sia's "Cheap Thrills," Ed Sheeran's "Shape of You," Drake's "Passionfruit," and even Taylor Swift's "Delicate"—notice the triplet notes? The tresillo is so prominent in music today because it lends itself well for layering in a variety of instruments. Its effective rhythm makes it a strong choice for pop artists (who tend toward simple, consistent, melodic beats) and has led to a new wave of clave-based bops that constantly top the Billboard charts.

So the beat goes on! Finding the legacy of early Afro-Cuban jazz is as easy as turning on the radio or turning up the volume on Spotify. To make the bridge more obvious, I've curated a mixtape all about the hitmaking, genre-transcending clave. Please enjoy the playlist below, shared from my quarantine to yours.