April 24, 2020

By Jon Mogul, Associate Director of Curatorial + Education

It's something we take for granted. We return home after work and find an assortment of bills, junk mail, magazines, catalogs, occasionally a birthday card, or perhaps a postcard from a vacationing friend. We may still go in person and wait impatiently in line to buy stamps or send a package, or we may just go to the website. But the United States Postal Service, established by an act of Congress in 1792, is suddenly in jeopardy, threatened by a combination of COVID-19 and larger political forces.

There is an inscription on the façade of what used to be the Washington, D.C., Post Office (currently the National Postal Museum) that comes from a time when the Postal Service meant a lot more to people than it does now—an inscription that people have started to notice again in recent days.

Messenger of Sympathy and Love

Servant of Parted Friends

Consoler of the Lonely

Bond of the Scattered Family

Enlarger of the Common LifeCarrier of News and Knowledge

Instrument of Trade and Industry

Promoter of Mutual Acquaintance

Of Peace and of Goodwill Among Men and Nations

If we lose the Postal Service, we will lose not only a key public service, but an institution that has shaped and enlarged America's common life since the nation's birth. That role is reflected in various ways in The Wolfsonian's collection (for example, in the thousands of postcards in our library). It can be seen most vividly in our holdings of studies for post office murals dating from the time of President Roosevelt's New Deal in the 1930s.

Let's get one thing out of the way. You'll sometimes see these called "WPA murals," referring to the Works Progress Administration, one of the key New Deal agencies. The WPA provided work relief to millions of unemployed men and women, including artists of various kinds, during the Great Depression. And it did commission many murals—we have a study of one, for example, painted in the immigrants' dining hall at Ellis Island.

But the hundreds of murals painted at post offices and other U.S. government buildings were commissioned by a different agency: the Treasury Department's Section of Fine Arts. And unlike most WPA murals, those in post offices were selected through a competitive process, in which artists sent studies for proposed murals to Washington, D.C., where they were evaluated by juries that selected the winning entries.

These studies make up a fascinating part of The Wolfsonian's collection. They date from a period when the federal government had a much smaller role in American lives than it does now—before Medicare, food stamps, and the Department of Homeland Security, and just at the dawn of Social Security and unemployment insurance. For many people, maybe especially people who lived outside big cities, a trip to the post office was just about the only regular contact they had with the government. So, post office murals were an important way for the government to communicate with the public.

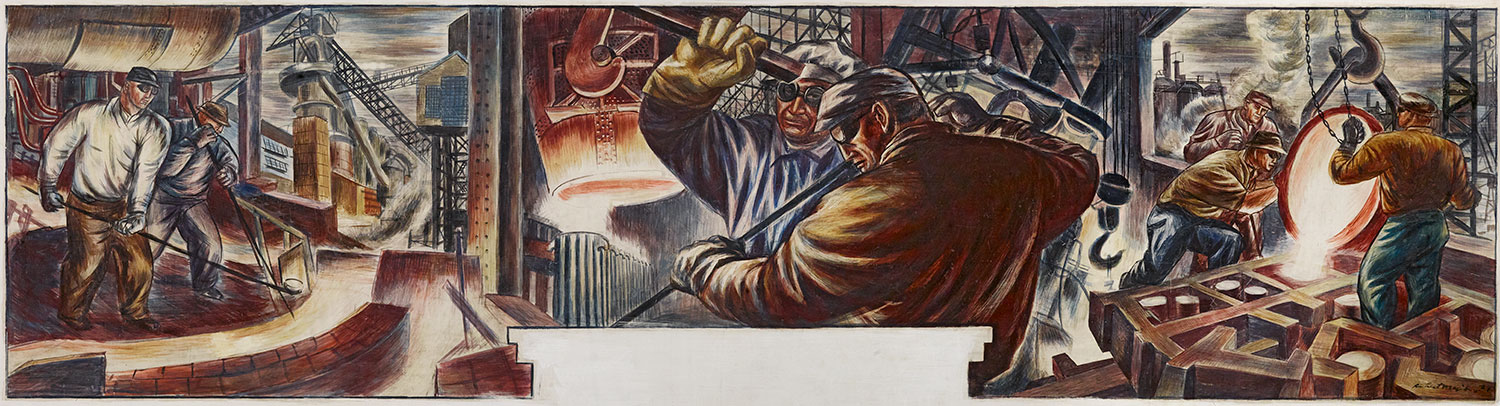

For the most part, the Treasury Department's juries selected works focused on themes that were relevant to the location of a particular post office. Often, this meant depictions of important industries or other key areas of economic activity that shaped the lives of local people. For Hubbard, Ohio, part of an enormous steel complex around the city of Youngstown, Hubert Mesibov took the opportunity to cover a full wall with a mural that demonstrated the different stages of the process through which skilled workers molded steel ingots. Jean Swiggett's mural, intended for Jasper, Indiana, conveys the balance between agriculture and industry for the town's economy; in the end, however, it was painted in a post office in the town of Franklin, about 100 miles northeast.

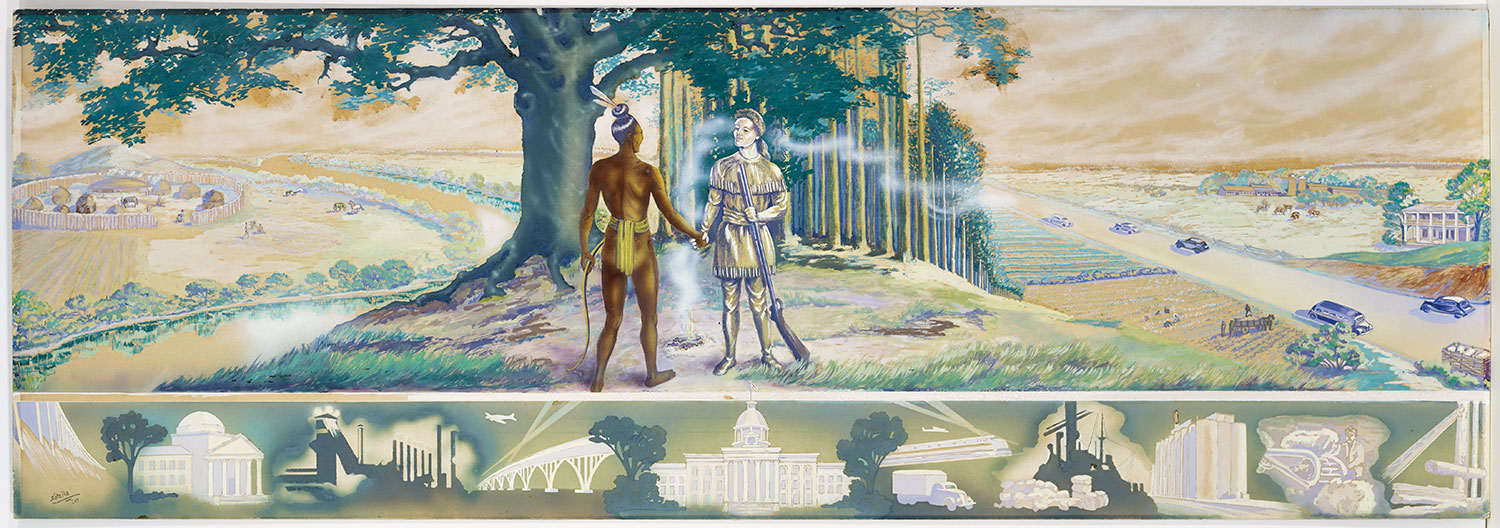

Next to economic life, local history was the other major theme of post office murals from this era. Very often, these works papered over troubling issues to present an idealized view of the past. Adelaide Z. Philips painted a handshake between a pioneer and a member of the Choctaw tribe as a symbol of harmony between the white settlers of the region and indigenous people. Missing from this narrative was the forced removal of most Choctaws from the region to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River, in the early 1830s. (Philips's study was not selected by the jury.)

Sometimes communities were unhappy with the murals that were proposed for their post office. The mural for the Safford, Arizona, Post Office is a case in point, as described by art historian Karal Ann Marling in her book Wall to Wall America (1982). The Section of Fine Arts selected Seymour Fogel's study of an Apache ceremony—which he developed from the work below—from among 58 submissions to a 1939 competition. When the selection was made public, the local Chamber of Commerce, backed by one of Arizona's senators, objected vehemently to Fogel's depiction of Apaches, whom they associated with attacks on pioneer families. Under pressure from Section officials, Fogel revised his proposal so that it consisted of panels illustrating the early history of the county, without depicting a single Apache.

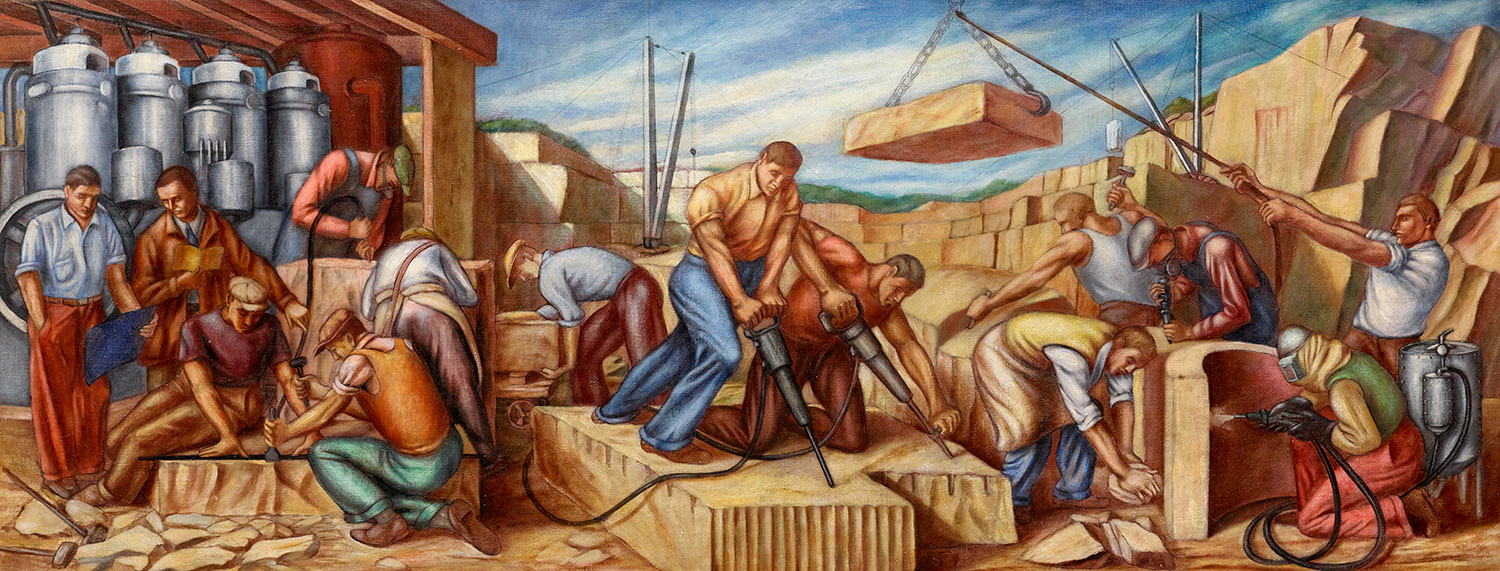

Citizens of Westerly, Rhode Island, were upset when the Section chose for their post office a railroad-themed design that, as Marling writes, did not seem to have much relationship to the town itself. Local leaders wrote back to Washington insisting that a much better, more locally grounded subject would be granite quarrying—a theme that a number of the unsuccessful entries, such as one by Leo Raiken, had depicted. In the end, Westerly’s post office did not get a mural at all. But Raiken did go on to paint his scene at full scale, and it hung for many years at the family’s cemetery memorial showroom in Brooklyn before coming to The Wolfsonian.

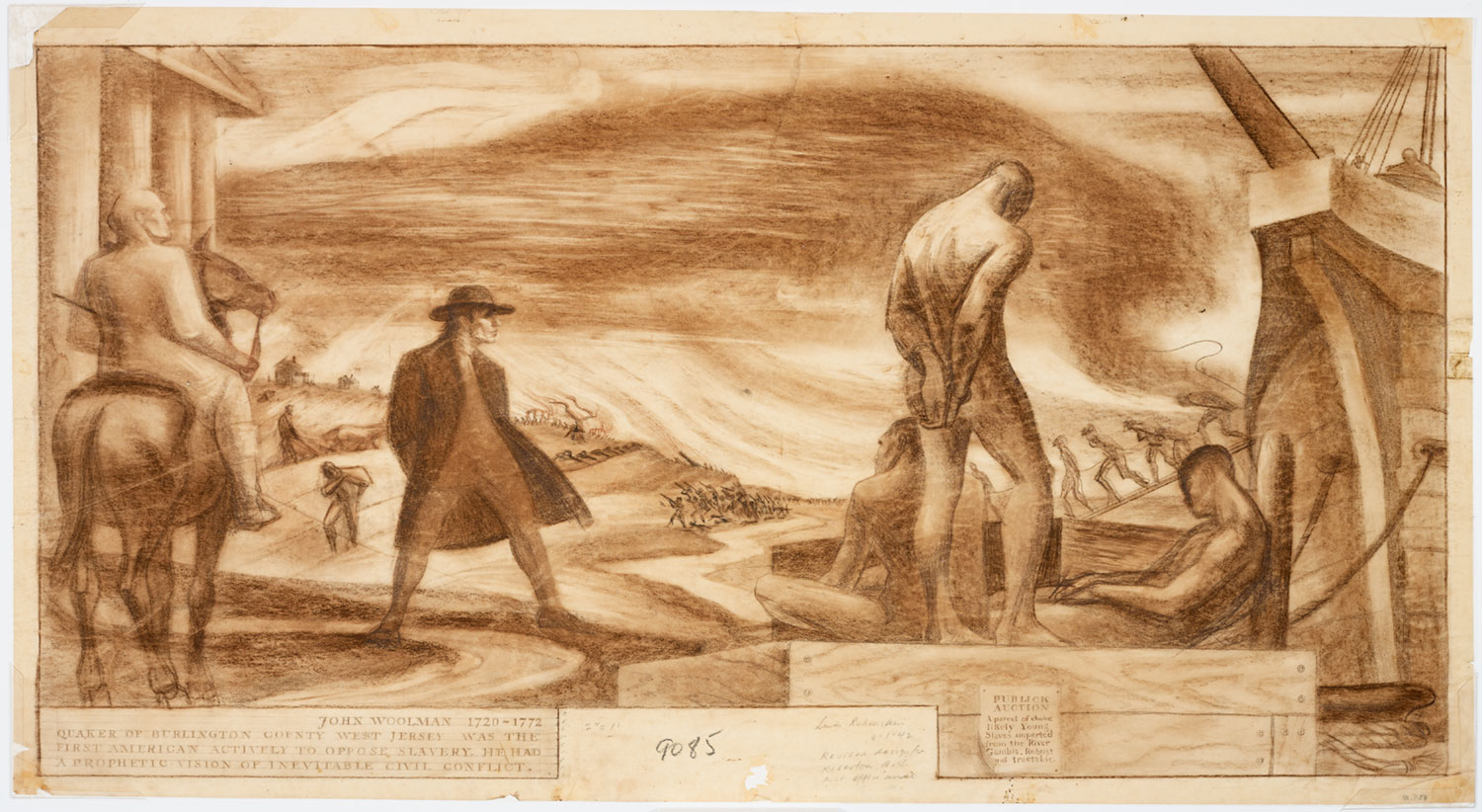

Many of the mural studies in our collection were competition winners and ended up on the walls of post offices across America. But some didn't, either because they were not selected by the juries in Washington, or because—like Fogel's above—they were modified beyond recognition in the course of execution. One of those to never see a wall is Lewis Rubenstein's study intended for the new post office in Riverton, a small town in New Jersey. To honor the Quaker settlers of Riverton, Rubenstein proposed a mural that would portray John Woolman, an 18th-century Quaker resident of the area and one of America's first abolitionists. Rubenstein's study shows Woolman witnessing a slave auction, while in the background soldiers wage the war that Woolman feared would be sparked by the institution of slavery.

Rubenstein won the commission just as the Second World War was beginning, but he enlisted in the Army before painting the mural. In 1947, after the war had ended, the government asked him to proceed with the mural. But Rubenstein no longer believed that the subject was appropriate for, in his words, "a tiny suburban community," and he wrote to Washington that he preferred to paint a different scene. When he got word that the change would not be permitted, the artist terminated the contract.

New Deal post office murals were public art. Like much public art today, they could be contentious, get embroiled in politics, and reveal differences in experience and viewpoint among members of the public. Some have not aged well, often showing the distance between then and now when it comes to attitudes about race and gender. Even so, we can look back in admiration at the effort not only to provide much-needed commissions to artists at a time of economic crisis, but also as a way to engage ordinary people, as they went about their daily lives, with art that spoke to them about their current experiences and shared history—enlarging the common life.