April 22, 2020

By Frank Luca, chief librarian

Contemplating the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, I'm struck by a number of ironies. As the COVID-19 pandemic forces the temporary closure of businesses and factories, keeps hundreds of millions of cars off the highways, and drives much of the human population into isolation, more has been unwittingly done to reduce pollution and greenhouse gases in recent weeks than purposefully accomplished in decades. But in another twist, though the air quality is unquestionably cleaner and the environment more inviting, many of us are stuck indoors under "shelter-in-place" or "safer-at-home" directives.

It feels odd to be celebrating Earth Day during quarantine as a natural pandemic is scything its way across the globe. The first Earth Day, held on April 22, 1970, has been described as the "birth of the modern environmental movement." As someone who grew up in that decade, celebrated Earth Day in school, and had my own views shaped by the ecology movement, I recognize the importance of marking the event and some of the critical legislation that followed; but, as a historian, I am also wary of focusing so narrowly on a single historical marker. Our own attitudes towards nature have significantly evolved even over the last 50 years through conflicts between the spiritual and scientific, climate change scientists and deniers. Earlier generations of Americans were also very much shaped by battles between pragmatic, "wise-use" conservationists and spiritual-minded preservationists.

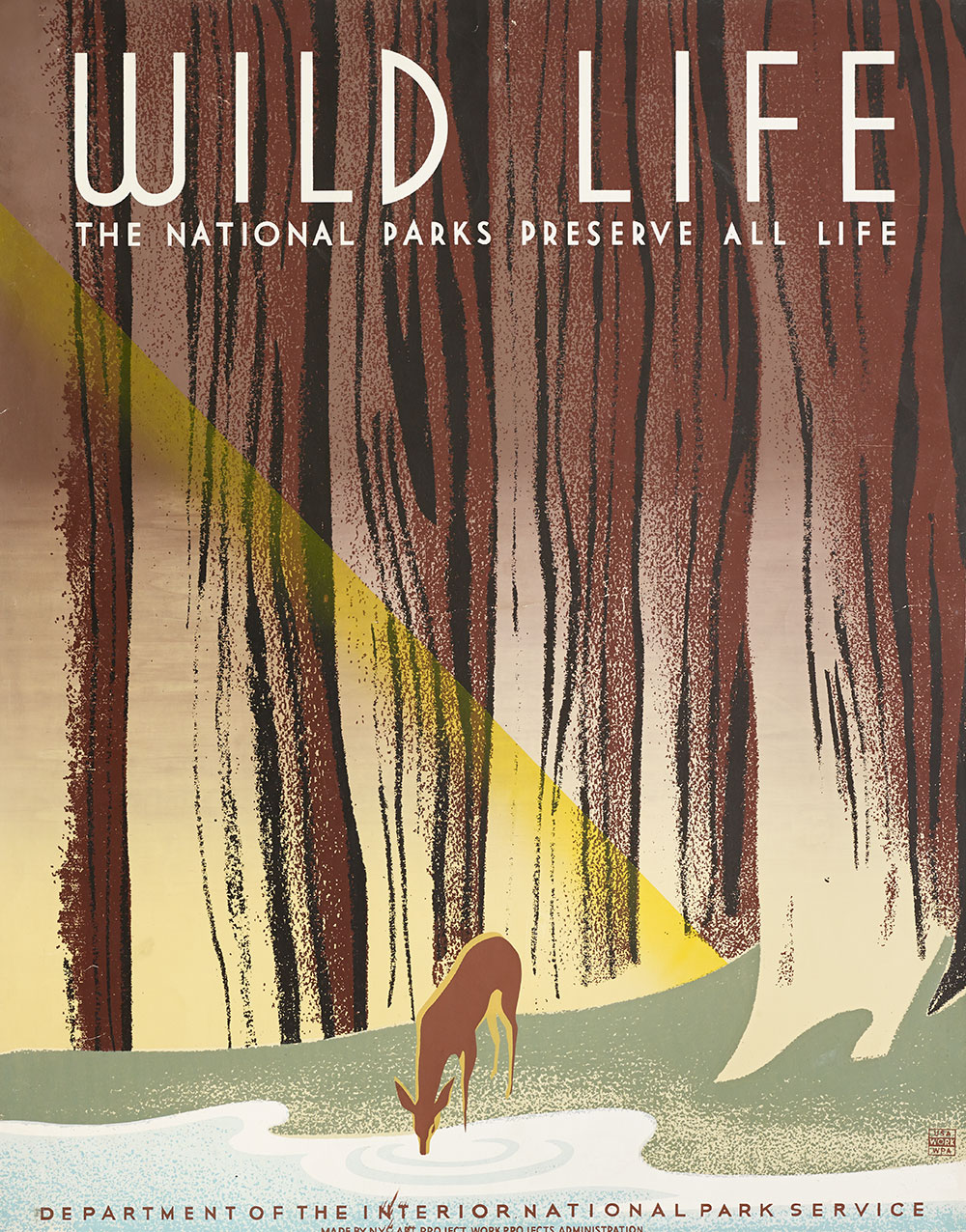

Poster, Wild Life. The National Parks Preserve All Life, 1939–43. Frank S. Nicholson, designer (attributed). N.Y.C. Art Project, Works Projects Administration, printer. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., publisher. Serigraph. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, TD1989.20.1.

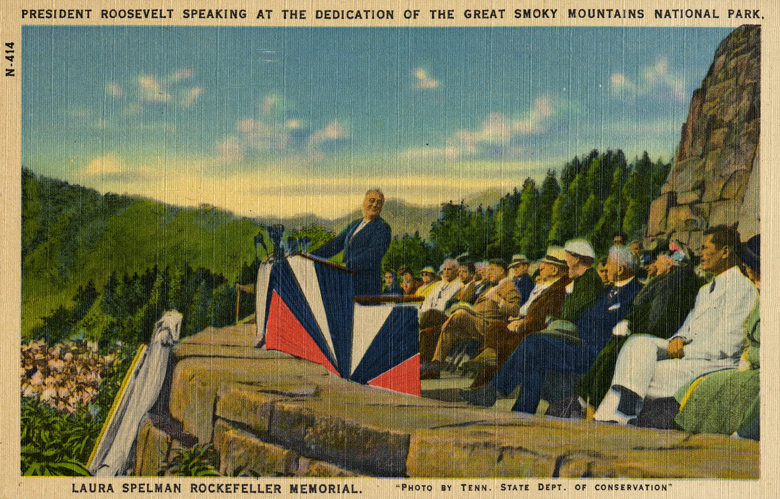

For me, it is the presidencies of the two Roosevelts, Theodore and Franklin, that mark the true beginnings of modern environmental consciousness in America. It was Teddy Roosevelt who brought environmental issues to the forefront, first by promoting the conservation movement to ensure the "efficient" use of natural resources, and then by dramatically expanding the number and size of the country's national parks and forests.

Book page, "Theodore Roosevelt," in The Life of William McKinley, 1901. P. F. Collier & Son, New York City, publisher. The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, XB1990.458.

Teddy Roosevelt convinced Congress to create the U.S. Forest Service and appointed Gifford Pinchot, a "wise-use" conservationist, to head the new department in 1905. After graduating from Yale, Gifford Pinchot's professional introduction to forestry came in 1892, when he was hired to manage the forests of the Vanderbilt family's Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. That same year Pinchot met and fell under the spell of naturalist and Sierra Club founder John Muir, who would become first his mentor and then his bitter adversary in the contest between forestry preservationists and conservationists. After embarking on a National Forest Commission tour of the West in 1896, Pinchot became a forest agent and later head of the Division of Forestry within the Department of Interior. Pinchot advocated a pragmatic management of forest reserves and natural resources guided by a "conservation ethic," in opposition to his former mentor, John Muir, who thought of wilderness and nature in more spiritually-affirming terms, insisting on their preservation rather than exploitation.

During the Great Depression, unemployment hit record heights which have only recently been surpassed in the wake of COVID-19. Back then, the nation was still grappling environmentally with the contest between conservationists and preservationists when Teddy's distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt, was inaugurated president in March 1933. Not only was the national economy in shambles, but the southern states were experiencing drought and significant soil erosion and degradation brought on and made worse by many decades of poor farming practices, strip-mining and clear-cutting by short-sighted mining and logging companies, and catastrophic flooding by the Tennessee River.

Postcard, Erosion in Copper Basin, Ducktown, Tenn., 1933. Cline Studios, photographer. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca and Clara Helena Palacio Luca, XC2010.01.2.18.

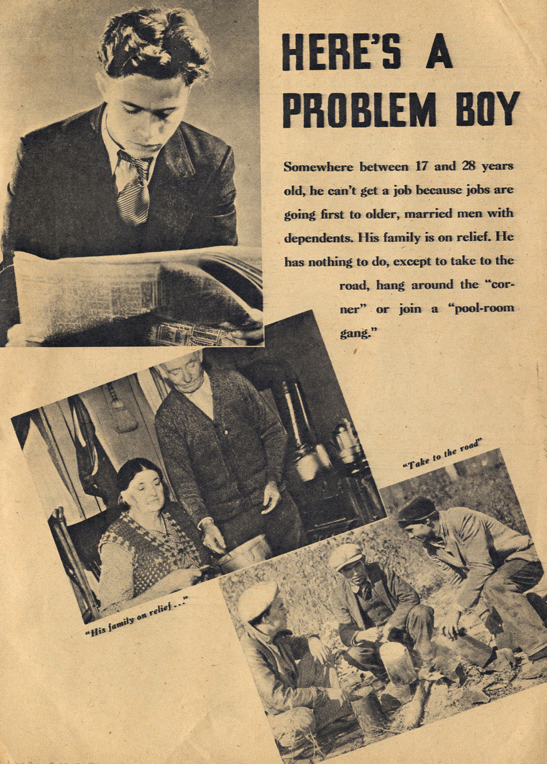

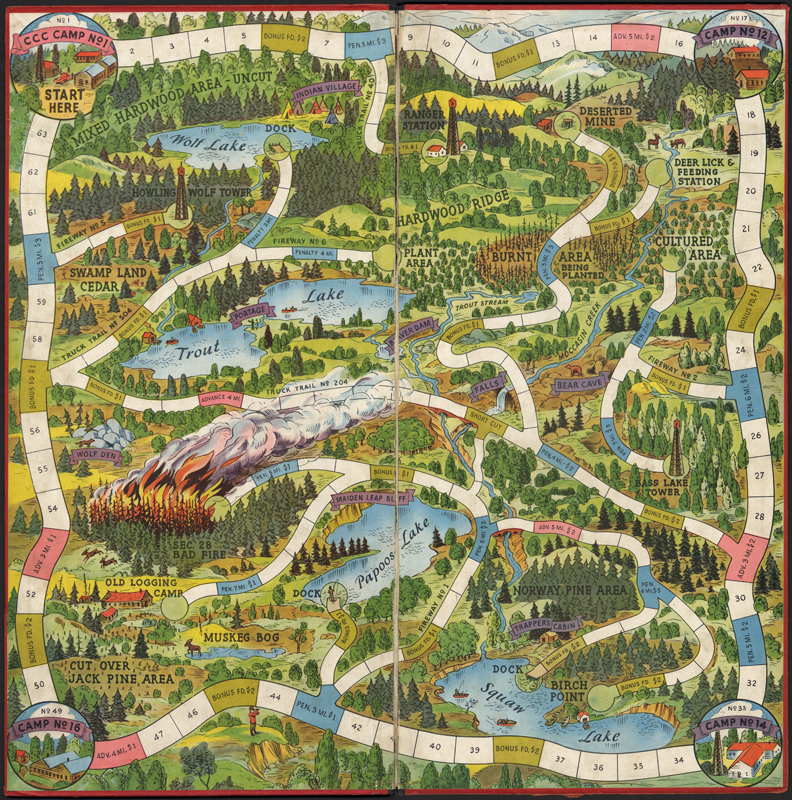

Within months of taking office, President Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Soil Erosion Service with the goal of addressing some of these serious environmental concerns. The CCC provided immediate employment for 250,000 young men, many of whom had dropped out of school, left home, hitched and ridden the rails to the big cities, and fallen into delinquency after a fruitless search for work.

FDR had been a longtime supporter of the Boy Scouts before being elected president and believed that sending these "street kids" to do forestry work in the natural settings of state and national parks and forests would be good for rebuilding their malnourished bodies and spirits. The CCC provided life-saving employment and vocational training and experience to millions of enrollees over the course of its nine-year existence.

The work these young men achieved in planting billions of trees, fighting forest fires, engaging in pest and flood control activities, blazing scenic trails, and building roads, bridges, and other park infrastructure made the nation's parks and forests not only more economically and environmentally sustainable, but also more attractive to domestic tourists.

Although many books have been written about the direct impact that Roosevelt's "Tree Army" had in restoring, developing, and revitalizing our natural resources, few have considered the long-term potential effects this work experience had on the enrollees. Several million young men had been taken from urban centers and housed, trained, and put to work in our parks and forests; one can only assume that many gained a working knowledge and new sense of appreciation for nature that they carried home with them and instilled in their own children.

Postcard, President Roosevelt Speaking at the Dedication of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, c. 1940. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca and Clara Helena Palacio Luca, XC2010.01.5.4.

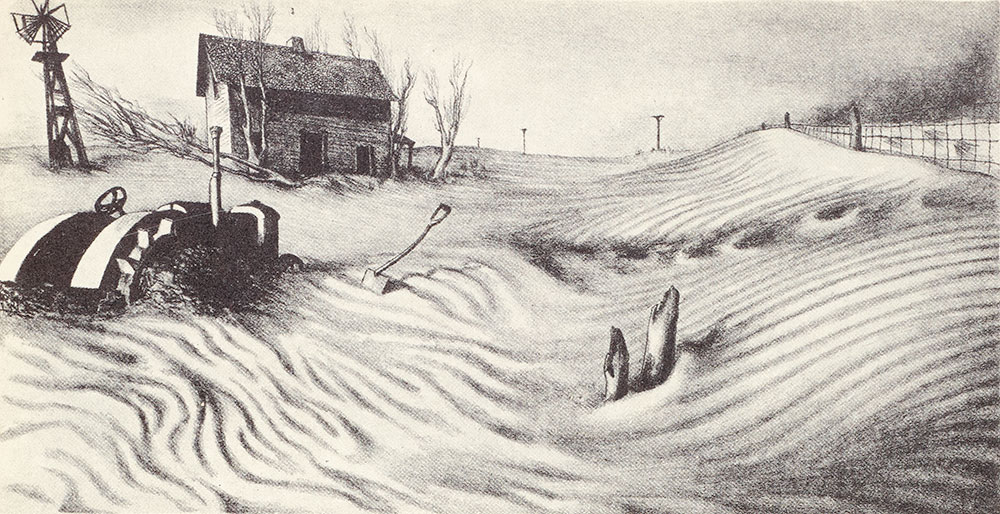

Roosevelt also signed into law the bill that created the Soil Conservation Service (or SCS) in 1935 as severe drought and dust storms rolled across the southern Great Plains. This natural and manmade ecological disaster robbed millions of acres of farmland of its topsoil, sent airborne in black blizzards that suffocated cattle and blanketed farmlands in dust.

Not unlike today, the farming families of the Great Plains were often confined within their homes for days, weeks, and occasionally even months. As the dust seeped in through every crack and crevice of their windowsills, the black blizzards forced even those indoors to wear wet cloths and bandanas over their noses and mouths to ward off fine dust particles that choked, sickened, and killed thousands of young and old with dust pneumonia. This normalization of covered faces in public is resonant of what we're witnessing today, as many establishments and metropolitan areas require people to wear masks to go about their daily business.

FDR's CCC and SCS employees aimed to reverse the damage of the dusters and desertification where possible by introducing farmers to contour plowing and by planting trees as windbreaks and a strain of Sudanese grass and sorghum as ground cover.

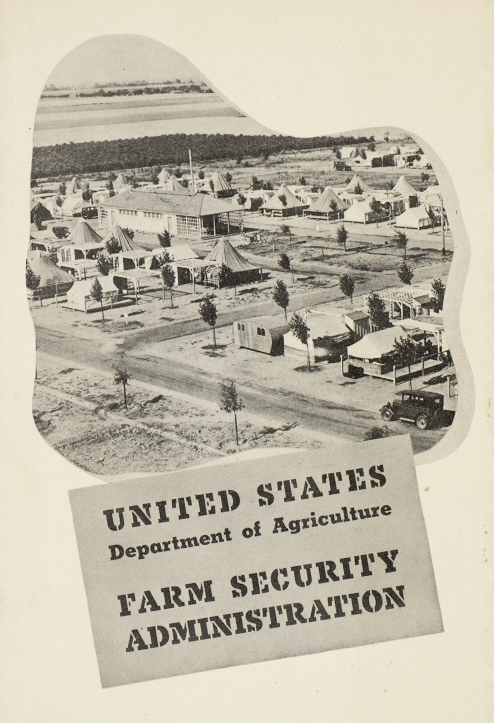

Similar to the emergency relief package recently passed by Congress to help businesses and individuals hit by the coronavirus crash, the Roosevelt Administration did what it could for those farmers living in or forced to leave dust-stricken areas determined to be beyond rehabilitation, like the Joad family of John Steinbeck's famous novel, The Grapes of Wrath. President Roosevelt's Resettlement Administration provided some with direct relief and others with assistance while they migrated to more fruitful areas of the country.

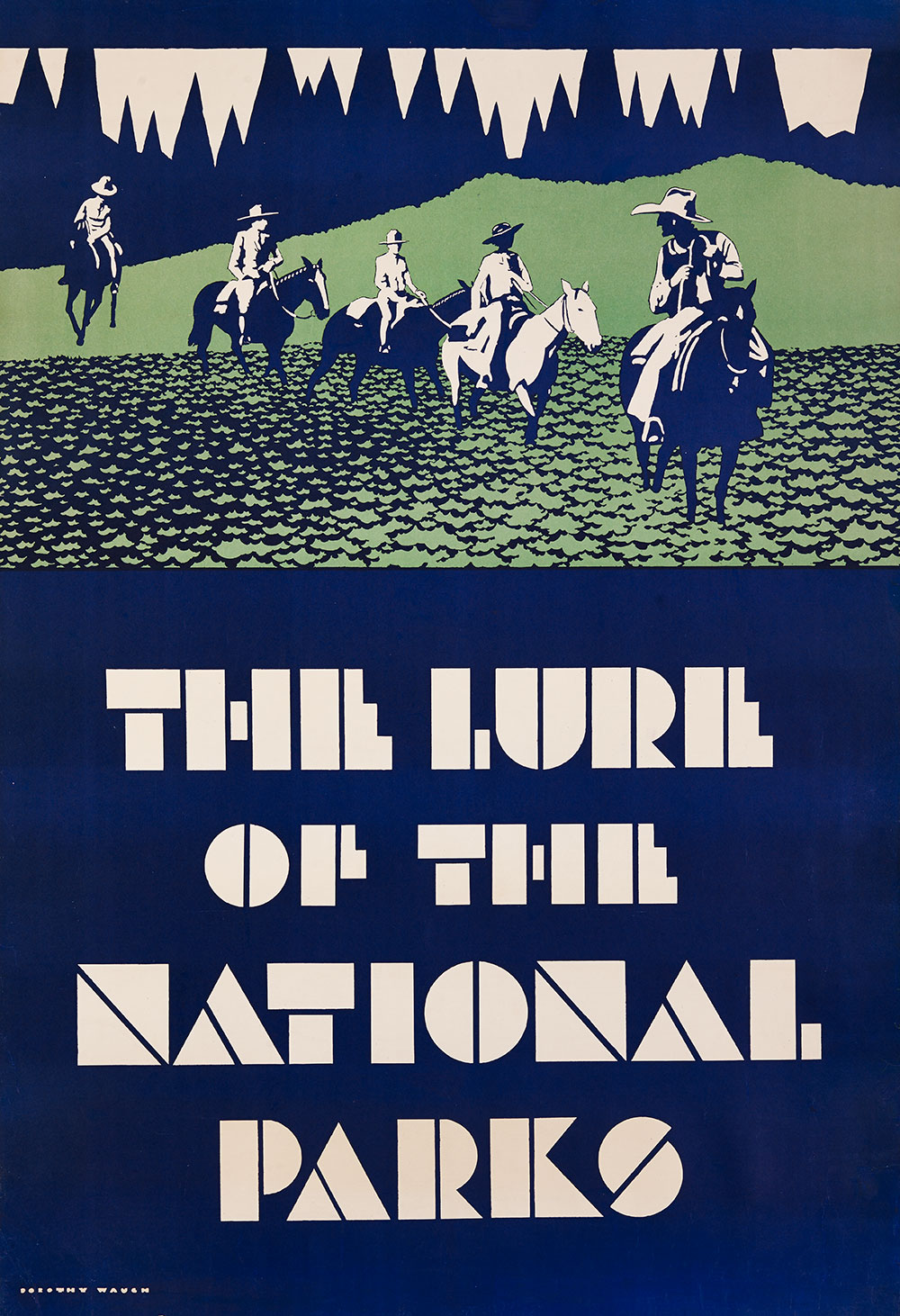

Even as the Roosevelt administration wrestled with the serious ecological problems of the era, the National Park Service did its part to boost the economy through domestic tourism by using artist-created posters to encourage Americans to vacation in the country's public parks.

In reviewing this history, it's clear that the story of our evolving attitudes toward protecting the natural world stretches much further back than the inaugural Earth Day—and there is a long uphill path ahead, too. I only hope that we can take cues from the two Roosevelts and their proactive measures and legislation to seize on the positive environmental side effects observed in COVID-19's accidental global experiment. When life returns to what it was, will the trends reverse, our lessons forgotten? We'll have to watch the skies and see.