April 9, 2020

By Frank Luca, Chief Librarian

Under shelter-at-home directives and working remotely from my condominium for what feels like months (though it has only been weeks), I’ve been obsessing on the COVID-19 virus that has transformed the vibrant tourist mecca of Miami Beach into a virtual ghost town. As a historian, I am always looking for parallels in history that help contextualize our present crises. As yesterday marked the official anniversary of the U.S. House of Representatives vote endorsing President Woodrow Wilson and the Senate’s declaration of war against Germany in 1917, my mind turned to the impact of the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 in bringing an end to that bloody conflict.

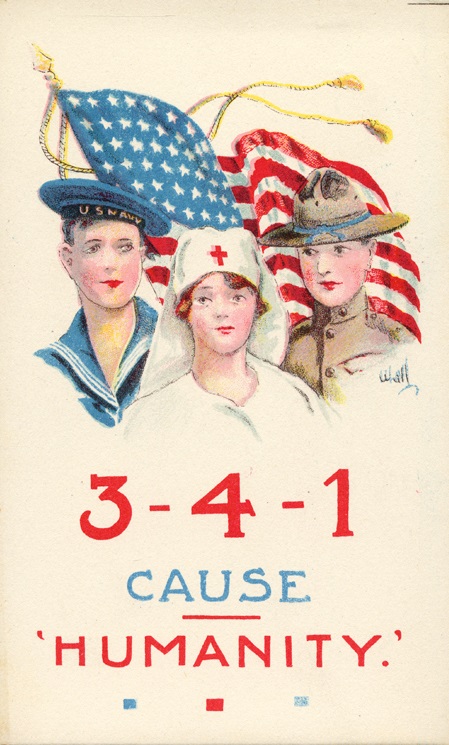

Postcard, 3-4-1 Cause: 'Humanity.', c. 1917. Bernhardt Wall, illustrator. Illustrated Postal Card & Nov. Co., New York. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Purchase, XC2006.09.5.33.

American history books frequently assert that U.S. military intervention in the war proved decisive to the defeat and capitulation of Germany, while often completely ignoring another important and consequential factor. Ironically, it was the outbreak of the so-called Spanish influenza pandemic that made the combatants on both sides of the trenches too sick to continue killing each other, and was one of the reasons the German High Command was compelled to call for an armistice.

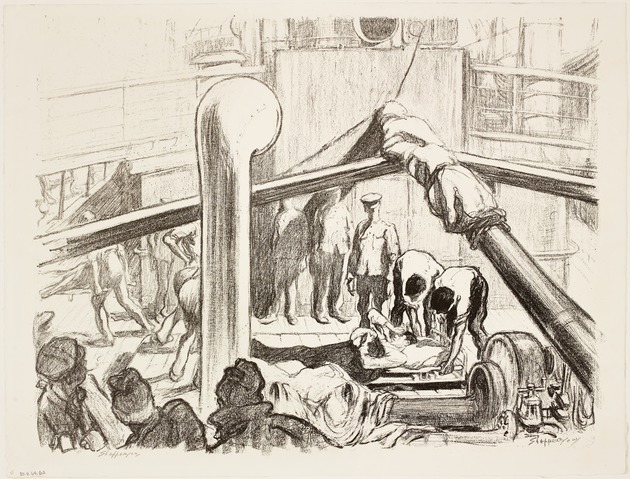

Plate XXXII, "American Red Cross in the Government School of the Légion d'Honneur, St. Denis, December 1918," from the American Army in France (1917–1919), 1920. Joseph-Félix Bouchor, illustrator. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Purchase, XC2012.03.9.

According to the most conservative tallies of the U.S. War Department, influenza sickened 26% of the Army—more than 1,000,000 men—and killed nearly 30,000 before they even completed the crossing to France.

While 53,402 American troops were reported to have died in combat, nearly 45,000 of the American Expeditionary Forces and 5,027 naval personnel succumbed to influenza and related pneumonia by the end of 1918. Another 106,000 of 600,000 American military personnel required hospitalization and were rendered temporarily unfit for combat duty. Other estimates suggest that influenza and pneumonia may have killed more American soldiers and sailors than died on the field of battle.

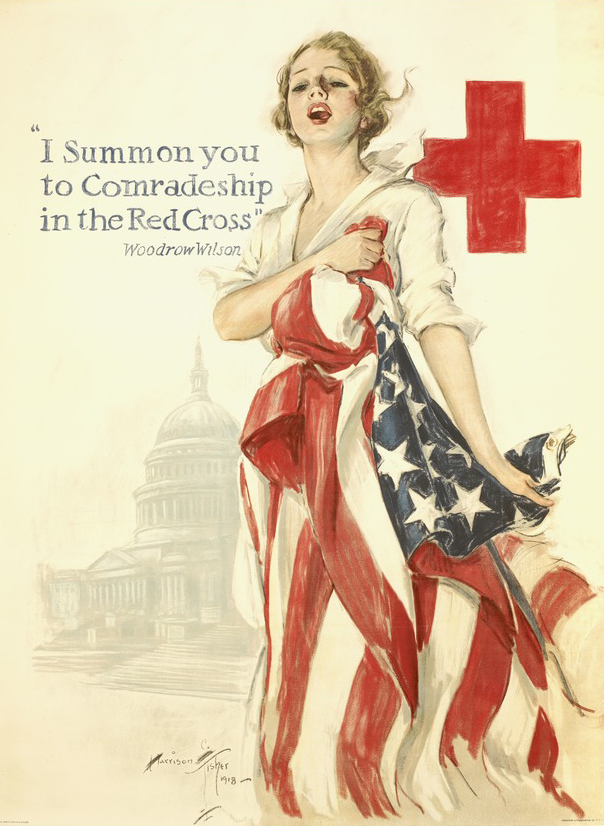

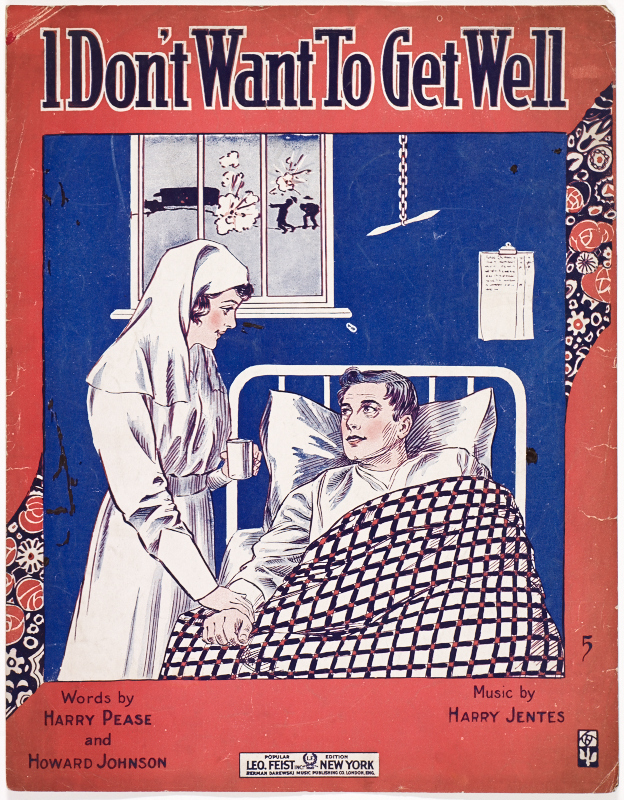

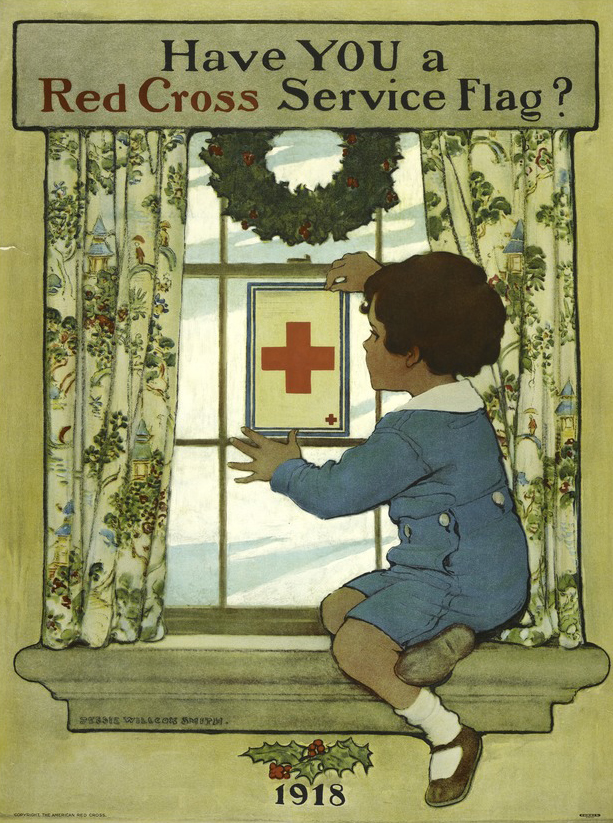

While much is often made (and rightly so) of the heroism of our troops, in light of the terrifying invisible enemy of influenza in 1918 and coronavirus in 2020, I thought that I would include some images that pay tribute to the unsung heroines working under the most dangerous of circumstances: the Red Cross nurses who tended the sick and dying.

These heroines, like their medical counterparts today combating COVID-19, are deserving of our profound gratitude.

Sheet music cover, I Don’t Want to Get Well, 1917. Leo Feist Inc., New York, publisher. The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca, XC2013.01.9.3.

One of the reasons so few people are aware of the impact of the horrendous disease in bringing the World War to an end was the fact that military censors of the belligerent nations made sure that newspapers minimized the effects of the epidemic on the battlefield and home front so as not to depress morale and embolden the enemy. The pandemic was most often referred to as the "Spanish flu" because Spain, as a neutral country, was free to publish accounts of the sickness and to report the staggeringly high death tolls within her borders. While the First World War was responsible for the deaths of some 20 million combatants and civilians by 1918, the influenza pandemic is estimated to have sickened 500 million people (or 28% of the population worldwide), and killed between 23 and 50 million victims across the globe.

In the United States, more than 675,000 Americans died of influenza in 1918. Adjusting for present-day population figures, this would have proportionally been the equivalent of 2.16 million deaths today. Like now, persons going out in public in 1918 were cautioned and in many cities required to wear masks over their faces. But whereas the coronavirus appears to be most lethal among the older and more vulnerable population, the influenza epidemic of 1918–19 claimed the lives of the relatively young and healthy.

My own family history may be indicative of that unusual and frightening demographic trend, as I remember my grandmother recalling the death of her sister during the 1918 epidemic. Thanks to the incredible sleuthing abilities of Wolfsonian staffer Larry Wiggins, I was able to piece together the contours of her life and premature death. Born in Italy on April 5, 1896, Jennie Mazzei was nine when she and her mother and sister Maria arrived in America in 1905; her father, Vincenzo, was already living in Watertown, Massachusetts, and paid for their passage. Just a few months shy of 16 years old, Jennie married James Micela on January 16, 1912, and bore him 3 children. While living with her husband and children in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the 22-year-old housewife took ill on September 25 and died of influenza on October 3, 1918. She was survived by her husband and kids Bruno, Teresa, and Angelina.

I hope that our readers and their families are spared such losses of loved ones during the current COVID-19 crisis. Stay indoors and stay healthy.